Growing up in Haiti, digital artist Day Brièrre was exposed to powerful visual languages; whether the striking symbolism from folklore intrinsic to the culture or the iconography of Catholicism, the Haitian surrealist painters like Hector Hyppolite or the stylings of Ghanaian barber shop signage. She tells writer Alix-Rose Cowie that every time she feels she might be recognized for a certain type of work, she shakes things up, and she's determined not to be put in a box.

Artist Day Brièrre finds peace doing the same thing over and over; until she’s truly over it. She can eat the same dinner for months which her friends find very distressing. Currently the dish of the day (after day, after day) is Frosted Flakes cereal with 2% milk, and rarely for breakfast. She’s going on two months now. Until the day when she becomes sick of it and moves onto something else. “It's the same with art,” she says. She finds she’s compelled to explore a topic or a technique over a series rather than just one artwork, but then she becomes bored with it and wants to try something new. Having just started grad school for digital art at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, she’s currently into finding repetition and patterns in nature.

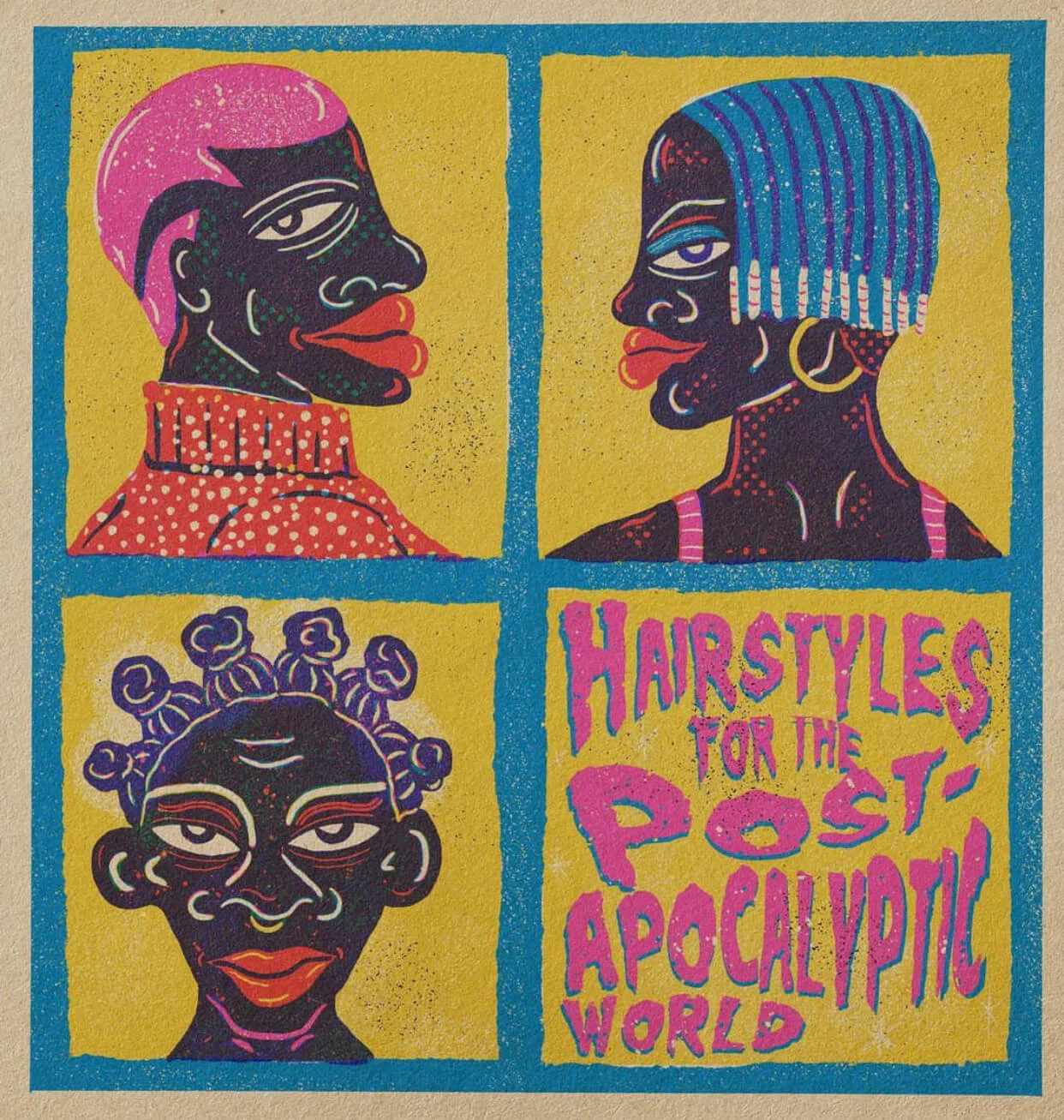

Brièrre was born and grew up in Haiti where she was exposed to powerful visual languages; the striking symbolism from folklore intrinsic to the culture and the iconography of Catholicism. She blends and borrows from both in her mystical, wickedly playful and color-saturated scenes, with more of a deep bow than just a nod to Haitian surrealist painters like Hector Hyppolite, and the stylings of Ghanaian barber shop signage. “I'm very inspired by folklore in ‘naive’ art, and outsider art in general,” she says. “I’ve found that I fit best there instead of in the contemporary art canon.”

Looking at Brièrre’s work, you can almost feel the catch of the paper through the computer screen, but she works exclusively digitally. “I’m very interested in making my illustrations look aged,” she says of the textures she adds. She manipulates the brush tools in Photoshop to produce a look just like grainy Risograph or raw woodcut prints. “Adding texture gives it some kind of nostalgia or it makes it palpable to me,” she says. “I mostly want it to feel like something you've seen before, like you already have a memory of this drawing. The textures are a way to explore memory in a tactile manner.”

Dinner

During the first two years of the pandemic, through isolation and the self-reflection it threw up, Brièrre’s own memories were jogged. She began thinking of her childhood and her younger self. She had felt lonely growing up. “I was a rowdy little girl, and I was misunderstood,” she says. “I feel like the only person who would’ve understood me is an adult me.” “Dinner” is an imaginary meeting between her adult self and her child self sitting down together at a table. The grown woman has long red nails like the kind her aunties would wear and the bowl of tropical fruit is what would usually be on the table in Haiti: mangoes, pineapples, bananas. “The kid is looking really mischievous which I feel is a good representation of me as a kid. I would have lots of rocks in my pockets and would carry around lizards,” she remembers. “I feel like my younger self is always accompanying me, in a sense, because my work is centered around playfulness or addressing issues in a playful way.” Sometimes Brièrre uses her art to address what’s going on in the world, “but this is a space where you can process things safely,” she says.

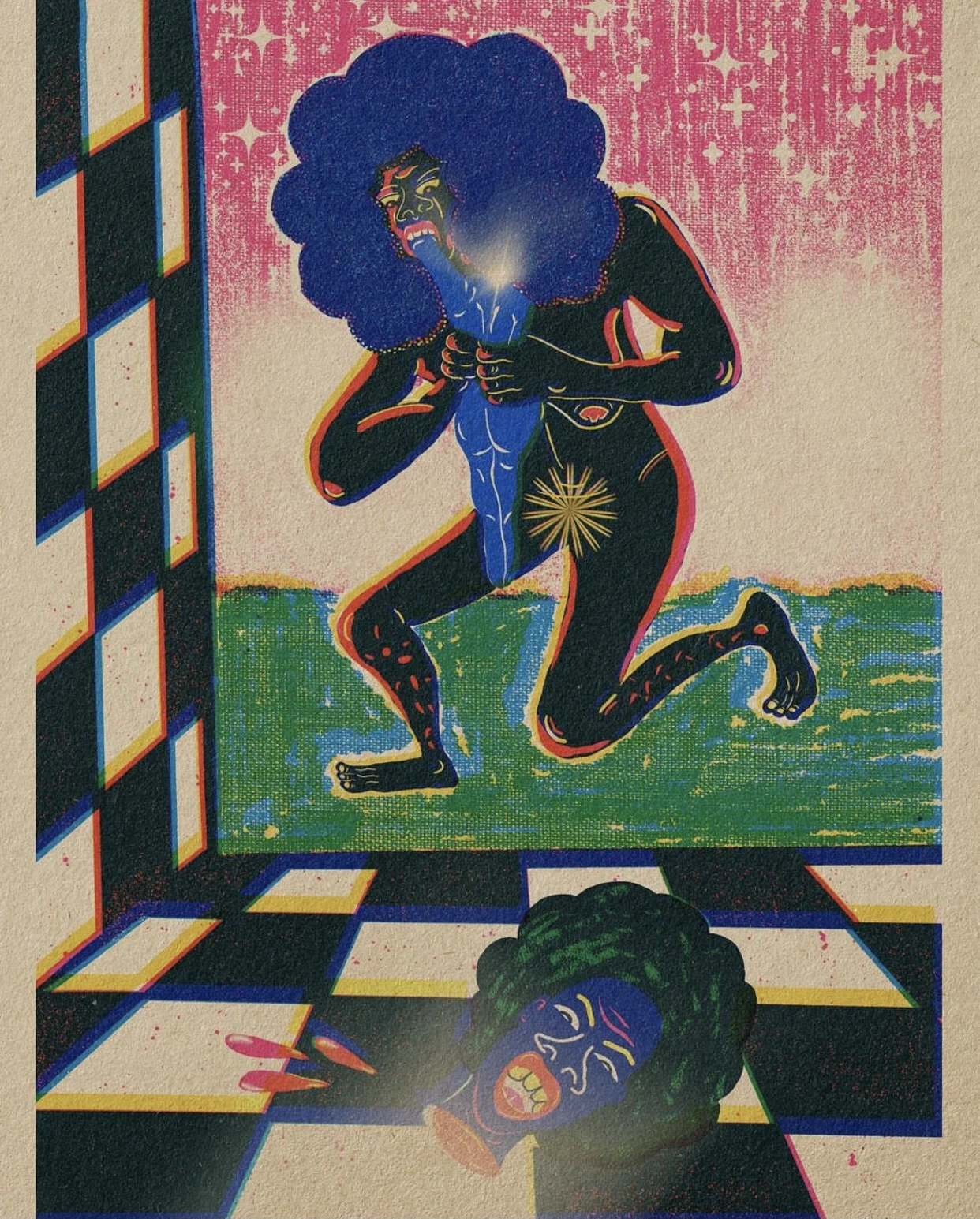

Saturn

One such example was when the supreme court in the United States ruled that there’s no constitutional right to abortion in the country. Brièrre processed some of her anger by reinterpreting Spanish artist Goya’s disturbing painting “Saturn Devouring His Son.” In her version the decapitated head rolls to the foreground, spurting blood. “It’s very gory,” she laughs. “I really wanted to put the popped off head in prominence.” The idea is that Saturn is the collective feminine eating toxic masculinity. It was inspired by a female rage so potent you could eat the person who hurt you. “[It’s the thought of eating] all the men who hurt us, who hurt all the women in my life,” she says. Brièrre sees it as an example of channeling her emotions into drawings. Art starts as an emotional process for her and when she sees others have an emotional response to it, it brings her a feeling of not being alone. “It's a way of connecting.”

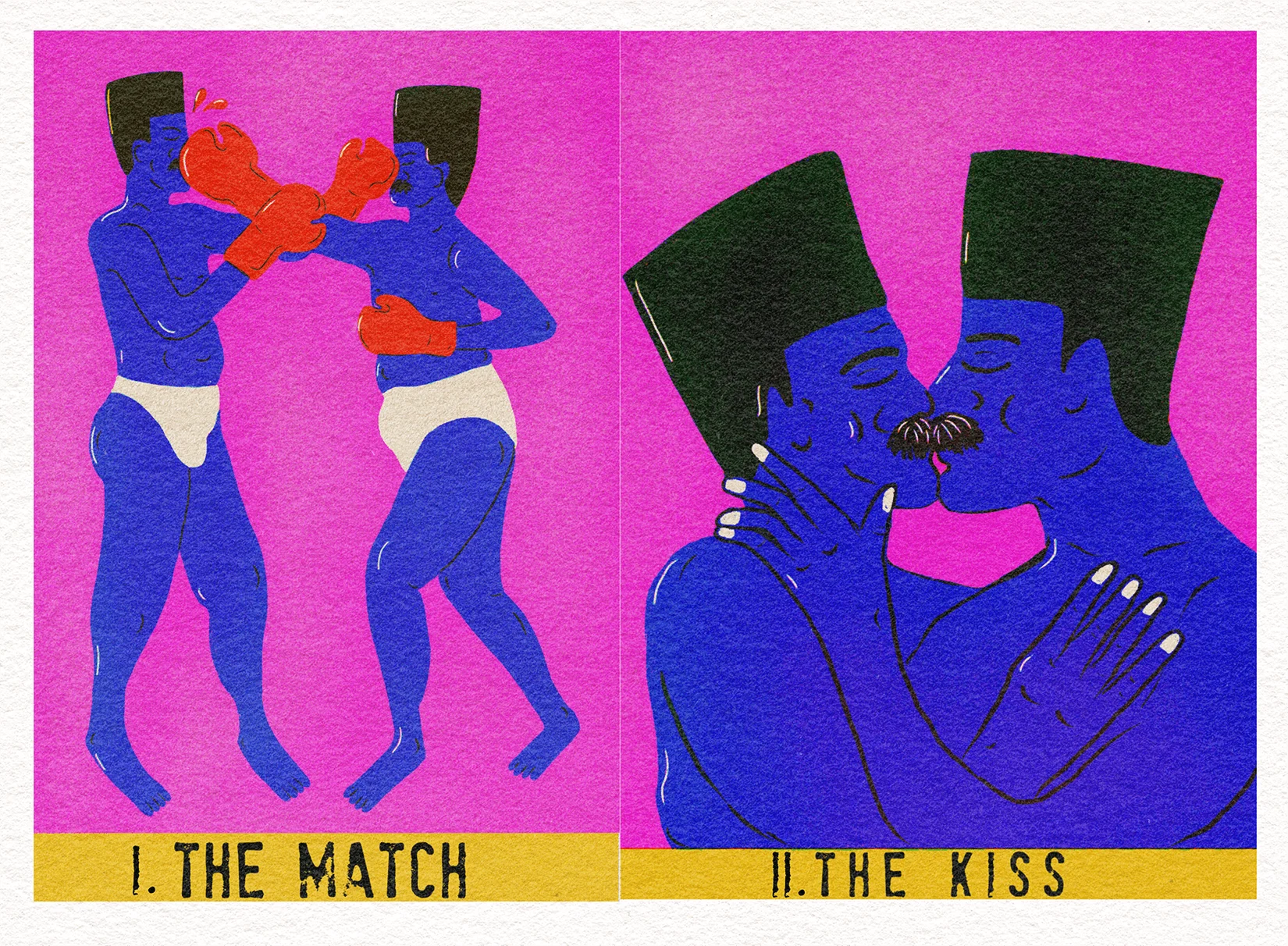

Match/kiss

By chance, a little while back, Brièrre came across a documentary about Senegalese wrestlers dedicating their entire lives to the sport and gaining many animated supporters. She became transfixed. “I was in awe at the dedication that these fighters put into their craft and was thinking about how this is an example of positive masculinity. They’re putting their thoughts and energy into this thing that’s very physical and very masculine, but it’s for good. It's this idea of a good fight,” she says. “I was really, really into it and I decided to make art out of it.” “Match/kiss” is the result, with a twist, because in Brièrre’s world, each bout ends with a smooch: “I thought it would be funny if they would kiss after every match.” The ultra vivid colors are Brièrre’s attempt at translating the excitement she felt watching the documentary, creating color planes if you squint your eyes.

Girlhood

For “Girlhood,” Brièrre was out of a color phase and into monochrome. “I always want to try something new and different in my practice,” she says. “I like to be experimental, especially with illustration. I also felt at some point people would recognize my color palette and I’d feel trapped. As soon as someone recognizes me, I feel trapped and I want to get out of that box that I'm put into. I don't even call myself an illustrator, I prefer it to be fluid and free-flowing.” Brièrre’s experimentation led her to discovering a way to emulate woodcut prints digitally by using nothing but the eraser tool. Starting with a black screen, she carved into it slowly with a small eraser brush like she would make a relief painting cutting out the negative space from a block.