Adversity has long been a goldmine for innovative new ideas. While members of the global creative community square up to difficult times in different ways, their aim is usually the same: to create and share something that will inspire, provoke and galvanize their audience.

With this in mind, we spoke to 13 filmmakers from around the world who decided to take a moment of global disruption, turn it upside down, and shake it to see what might fall out of its pockets. Duly inspired, they each made a short film which speaks to the power of creativity to rewrite the narrative in the face of challenging times. As for the future of creativity? It will never be the same – and that has never seemed so exciting.

CREATIVITY

For some, creativity has always been a matter of problem-solving. Designers create innovative solutions for everyday predicaments; novelists write to answer questions they pose to themselves. But when the “problem” itself is “how can we create right now?” that’s when things get interesting.

For Monica O’Hara and James Hurley, the answer was in the question itself. When the two filmmakers and friends found themselves unexpectedly bunkered down on opposite sides of the US, this project was a welcome opportunity to collaborate. How to be Creative presents a wry, witty take on the process that followed.

“This wasn't our idea at all!” Monica explains. “We had a few different stories that we were trying to do and we kept getting stuck. We just couldn't get past it. Then, it came to us. We said, ‘let's make a spoof about what we're going through right now.’”

Their film became the how-to of how-tos – a record of the dead-ends, meandering journeys and newly forged paths required to make anything worth making. What started out as “failure” became a fertile ground. “A lot of the jokes in the film were rooted in our trial and error,” says James. “We knew we wanted it to be a comedy, because we were laughing 90 percent of the time. We didn't always know where it was going, but we were having fun along the way.”

And in the process, they found a way to future-proof their filmmaking practice – no big crew required. At a time when so many productions have been postponed, friends are looking to one another to collaborate on more home-grown projects. Suddenly, a crew of two is stepping in for a crew of 200. Directors are asking, is there a way we might work around this? Perhaps we can use stock footage instead?

For LA-based director and editor Thomas Macvicar, the answer to the question “how can we create right now?” was to try something new and explore and experiment with his own ways of working. He decided to mine his relationships with family and friends to guide his film, Across the Triangle of Thoughts – a flowing, frantic, dreamlike collage. “I have hundreds of voice memos on my phone,” he explains. “They're combinations of scratched voiceover for commercials, or notes to myself, or sounds that I thought were interesting. I dug around to find ones specific to my family.” The film became a window onto his own life, infused with grandeur and melodrama, and set to a quick pace.

For Kelsey Rath, as for so many artists, creativity has been a balm during this time. “My mom is an artist as well, and she said to me, ‘what a gift it is to have creativity at a time like this!’ That stuck with me.” Her surreal film, The Sweet Escape, paints creativity as a joyous, technicolor antithesis to a drearily dystopian world.

And for all of the filmmakers, this unique project made collaboration possible, and on an enormous scale, when the barriers to that seemed insurmountable. Working with Adobe Stock allowed them to collaborate, indirectly, with thousands of other creators – drawing inspiration from their work, recontextualizing clips alongside one another, finding new reserves of energy they didn’t know they had. All of which goes to show that sometimes, disconnection is all the push you need to realize that you’re connected, in fact – and to a global community.

PERSPECTIVE

There’s nothing like finding yourself stuck indoors, along with millions of others on the Earth’s surface, to remind you that you play a tiny part in a miraculous global ecosystem. Several filmmakers, compelled by this idea, decided to play with a sense of scale in their films, to poignant and awe-inspiring effect.

Take Israel-born, New York-based writer, director and musician Daniel Koren. Time spent at home alone made him feel “more connected to everybody in my life – even people that I don't know,” he says. And that, in turn, fed through to his process for making this film. “You can find anything and everything on Adobe Stock! Rather than try to make a narrative with the footage, I was like 'okay Daniel, what do you really want to say?’”

The answer manifested itself as a light, philosophical, touching reflection on happiness – the kind of film which might change the way you look at the world. Titled Possibilities, it is a visual collage, narrated by Daniel himself, which positions every human being on Earth as part of a vast, interconnected web. “If I had to sum up the message, it's that happiness is a state of mind,” he says.

We become happier people when we identify ourselves as bigger.

Moreover, happiness is closely tied up with our sense of scale. Negativity, anxiety and agitation are all emotions synonymous with feeling small and overwhelmed, Daniel explains: “We become happier people when we identify ourselves as bigger.” With this in mind, the process of making Possibilities was something like one long meditation.

Working this way allowed Daniel to trust in his own intuition. If nothing else, he and the other filmmakers discovered, interrupting the routines and processes we create for ourselves can allow us to turn our hand to different things. To do something entirely new, with exciting repercussions.

Similarly, Argentinian director Pablo Fusco’s poetic short film, Hogar, or Home, serves to reframe human beings as a species among many others living on the earth’s surface. In the grand scheme of things, we are small and insignificant, he demonstrates, and that can be profoundly inspiring.

Beginning with a shot of the Earth in outer space, Hogar moves slowly inwards, emphasizing the wealth of landscapes, wildlife and different kinds of people who share our planet. But more than simply a visual collage, Hogar is an invocation. “It is a small reflection on the importance of putting aside for a moment all our differences, to realize that this is the only place we have to live,” says Pablo. “That it is beautiful, and we should take care of it a little more.”

For Pablo, as for Daniel, the idea of scale has been key this past few months. The director is used to traveling around the world for work, shooting in different countries and with different crews, but this moment of interruption has encouraged, and at times forced, him to make his world a little smaller. Nonetheless, film allows him to connect with and inspire people globally. Expansive, agile and restorative, it is a medium which can be adapted according to each creator’s requirements, he has discovered, without feeling any less impactful.

Director Anthony Gaddis experienced life in lockdown in St. Louis as an opportunity to truly sink into his creative process. “I knew that this was going to be time for experimentation,” Anthony explains. “I wanted it to be good and feel good, for me and for other people, after a month of staring at the walls.”

Wilding is a hypnotic, vivid whirlpool of a film – verdant green plantlife, luscious flowers and big cats all rotating as the viewer moves through a central tunnel, before giving way to a single bird soaring into the distance. It was also an exercise in flow state, Anthony says. In lockdown, he found he could experience whole days at a time without any “smash cuts,” or interruptions to the flow of his process.

Wilding’s soundtrack was inspired by exotica, a genre that has soundtracked this period for Anthony. “They're early hippies who moved from the East Coast to the West. It’s filled with nature sounds and ambient jazz, a lot of bird sounds. When the visuals for Wilding were made, I started looking at Adobe Stock audio and through the Epidemic Sound content I found a track called Jungle Blue. It had a lot of the elements of exotica that I liked, so I pulled out some of the instruments and a lot of the staccato, which I felt gave it a little bit more flow, and built a huge, deep bed of animal sounds that relate to the things that you're passing.” He used Adobe Premiere Pro more for the audio than for the visuals, he explains. “That entire sound bed of 50 or 100 layers of insects and animals and breezes and falling trees, those are all little clips that are layered in Adobe Premiere Pro.”

As for simply listening – he’d encourage anybody to do that. “It's a great meditation,” he concludes. “Sit and listen. See what you hear.” The outcome might surprise you.

CONNECTION

Ever since human beings first began making art, we have mined our complex relationships with one another for subject matter. And under lockdown conditions, when so many have been separated from their loved ones, human connection is a particularly powerful topic.

Osaka-born director Yukihiro Shoda’s (Sho) mission for his short was to make people feel connected. “I wanted to make something cheerful,” he explains. For the past three years, Sho has been based between Tokyo and LA, “learning a lot about Western culture and watching American films.” To his mind, Hollywood distills the essence of Western values into their purest form. What better way to lift an audience’s spirits? “I thought, if I can get images of the universe, maybe I can make a space scene that's inspired by Frank Capra's It's a Wonderful Life.”

The resulting short, Wonderful Lives, depicts a huddle of “second-class” angels, briefed by God to bring love and positivity to the troubled global community as they attempt to navigate the health and socio-economic crises triggered by the pandemic. It’s a heartwarming tribute to Capra’s film, reimagined for a contemporary audience. “Adobe is like the god, and the directors are angels, delivering positive messages to the audience, the people in quarantine,” Sho says. “Maybe corona made me kawaii?”

Croatia-born, London-based writer and director Daina O. Pusić couldn’t help but let everything she was feeling during lockdown seep into her short. “Which was mostly this confusion about whether I felt lonely, or whether I felt connected to everyone, because everyone was lonely at the same time,” she explains. We Fight But You’re Fabulous interrogates her narrator’s relationship with the world at large through the prism of his relationship with his mother – to witty, poignant and intimate effect. “I always have a running dialogue with my mother, my grandmother, my great-grandmother,” she says. “There's a strong Eastern European female voice in the background of everything I do.”

This informed the script, which, though so specific, is innately relatable. “In times of crisis, things tend to get very generic,” she says. She felt the importance of going against this particular grain. “I think people are made to feel comfortable when they are presented with oddness, because they feel less odd themselves.”

Like Daina, Atlanta-based writer, director and animator Zae Jordan is well-versed in observing, pinpointing and then recreating interpersonal oddness for his hilarious, offbeat shorts. My Little Duck observes how a new relationship – between co-workers Deonté and Tracey – changes when Deonté’s roommate, a tiny duck, is introduced.

Pared back though his animation style is, the long pauses in the characters’ conversation, the uneasy shifting of their eyes, the comic tension in their exchange are all painstakingly reminiscent of real life. “I focus on facial expressions,” says Zae. “The mouth articulating the words, the way the tongue moves when they say the 'l' in 'little'. It makes it feel more relatable.” The first thing he set out to find, when trawling through Adobe Stock’s huge archive, was the duck. “I had to find that good duck close-up, where it low-key looks at the camera,” he says. “This was the only duck that could pull it off.”

Cute and funny though it is, the duck is an embodiment of Deonté’s anxiety, fear and insecurity. “I wanted to create this world where people just have ducks,” he adds. The duck allows Zae to address the stigma around mental health. But it’s also about giving his viewer relief. “I want people to laugh!” he says. That's the beauty of making art; you can distract people from whatever they’re dealing with. Laughter is like a breath of fresh air.”

Maybe this is going to be another of those times. Maybe everybody will one day tell their quarantine stories.

Like Daina and Zae, director Graydon Sheppard found himself drawn to depicting an intimate relationship. His short film, Muya, tells the touching autobiographical story of his coming-of-age, when he spent a semester living with a close friend in Switzerland, and came out about his sexuality for the first time. Why this topic? “Maybe things feel monumental right now,” he says, from a cabin in his hometown near Ontario, Canada. “Maybe this is going to be another of those times. Maybe everybody will one day tell their quarantine stories.”

He’d dug out his photo album of that trip before lockdown started, so piecing the film together was a process of matching up those photographs to Adobe Stock footage. Which, he says, allowed him to make changes that ordinary filmmaking wouldn’t. Usually, “you have to plan, plan plan, and then you have your shooting days, and that's it. This process was great because it felt limitless. And also scary, because it felt limitless.”

Surreal and snappy, the film plays joyfully with memory, using graphic effects and clever cuts to create playful, vivid scenes in Switzerland which contrast directly with the comparatively closed life lived in Canada. “I love using fast edits and throwing everything at the viewer really quickly,” he says. “I let myself be open to taking an image and making it a little bit more special, wherever I could.”

For Sho, as for Graydon, the relative simplicity with which the film came together demonstrated that perceived blocks to the filmmaking process didn’t need to stop it altogether. “I learned that you can be creative under any circumstances,” says Sho. Graydon took a similarly can-do approach. “My dad gave me this mug ages ago, and it says, 'do what you can where you are with what you have,’” he adds. “If you really want to make something, but it feels impossible, there might be a way that's in your hands right now.”

After all, emotional experiences evoke emotional responses. As each of these filmmakers learned, sometimes it’s the situations in which making anything feels impossible, that the most intimate, powerful, universal stories present themselves for telling.

FUTURE

In a time when so much is uncertain, one thing is for sure: this experience will shift the way the creative community moves forwards. It seems more like a community – united, cohesive, with shared aims and shared experiences – than ever before. So how do we move into this strange new world? And what should we take with us, and leave behind, when we go?

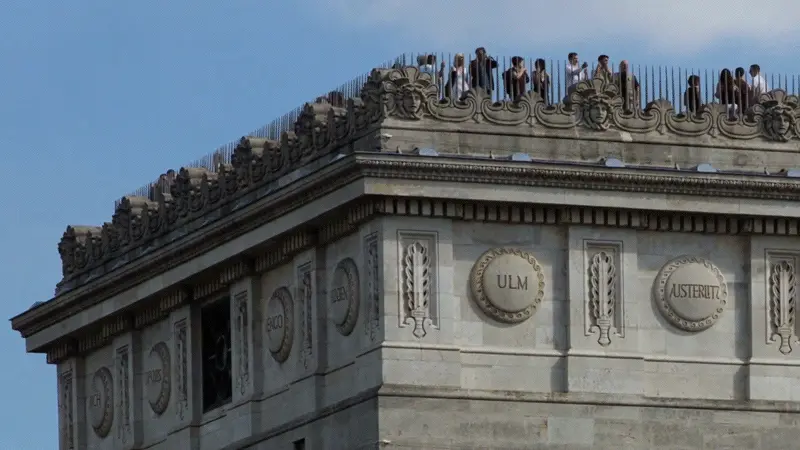

London-based British-Asian director and photographer Vivek Vadoliya hadn’t intended to make a film about his experience of Coronavirus. But he couldn’t get Arundhati Roy’s powerful piece for the Financial Times, entitled The Pandemic is a Portal, out of his head. “I was so fearful about what was going on in India,” he says. “But her last paragraph, which describes the pandemic as a portal – that we're going on this journey, we need to travel lightly, step forward into a new world? I thought that was spot on.”

His film, The Portal, became a visual representation of everything he is thinking about, a collage of clips which move through destruction towards what this exciting new future landscape might be. In dance, he found a way to express emotion without needing to describe it. “I've been watching lots of ballet and contemporary dance in the last year,” he says. “I was looking for movement which felt like it had friction, tension. What I really liked about working with Adobe Stock was recontextualizing images into something different, giving them new meaning. It was fascinating finding those clips, and pulling them together in different ways.”

The Earth has regenerated itself more than seven times in its history, from super-volcanoes, from asteroids.

Nature played a powerful role, too – flower motifs, blossoming in super quick time, in particular. “I’ve been reading a lot about the environment,” he says. “The Earth has regenerated itself more than seven times in its history, from super-volcanoes, from asteroids. It has always come back. I wanted to incorporate this idea of rebirth and regrowth.”

With these symbols of hope and forward movement, Vivek motions towards a not-too-distant time when creativity is more agile, in how it is executed, and more unifying, for the audience it reaches. As Roy writes, of this particular interruption: “It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.”

But what does it mean to interrupt a way of thinking? This year has seen a global renewal of conversations around social and racial justice – topics which shape every aspect of our everyday lives. This moment manifested in filmmaker Jasmine McCullough’s work, in the form of a video essay.

Classified interrogates our understanding of labels, and how they are used and misused in contemporary culture, through a series of conversations between the filmmaker and 13 of her close friends, family and co-workers. From race to gender and sexuality, the pervasive impact of using inaccurate language to define people is the central theme of the film, which feels honest and authentic in its attempt to confront an expansive and ever-changing issue.

Abstract, expressive and narrative fragments, all overlaid with a VHS-style effect for cohesion, create the emotional tone and texture of the film. But its most startling feature is the black frame which begins by blocking out all but a close crop at the centre of the shot, and expands as the film progresses. By the end, the entire contents of the screen are visible, and as the frame continues to creep outwards at the border, it almost feels as though it could continue to grow beyond the limits of that rectangle, exposing our everyday lives.

It is a poignant apparatus for forcing the viewer to reckon with their own clumsy attempt at definition. “At the beginning you are hearing this audio, and you find yourself focusing on what's happening in the box” says Jasmine. “You're trying so hard to figure it out – then, midway through, you realize that those voices are telling you, ‘no, stop trying to figure me out, just listen to me’.”

Simple and effective, the film nods towards one way we might all make a change – by starting difficult dialogue. “We are so ingrained in our habits, and the ways we have been conditioned to think about each other and the world. But I'd like to think these conversations have opened me up to think more deeply,” says Jasmine. “Labels are not necessarily bad. They're a tool. But we can't let labels box us unto our own ways of thinking.” Classified serves as a call to arms for all who watch it; ask questions, expand your definitions, move beyond what you thought and learn anew. The future will be all the more exciting for it.

Istanbul-born, LA-based director Taylan Sinan Yilmaz is thinking about the future too. The concept for his provocative film was dreamt up in collaboration with his friend, creative director Okan Usta, and while the premise is simple – “using two different images to create a new meaning” – the impact is powerful.

It is aptly titled The Bubble. “We create our own bubbles to protect ourselves,” Taylan explains. They decided to work around the bubble motif, placing subjects inside it that are vulnerable to those outside. Say, a woman working out, against a background of pasta. She is ostensibly motivated by her health – but as the background switches to a count of followers on social media, suddenly she seems driven by the validation of others, instead. Later, balloons hang dangerously close to a prickly cactus; a man surfs against a powerful image of refugees’ now empty life-jackets, piled high. With each watch, a new juxtaposition reveals itself to the viewer.

We create our own bubbles to protect ourselves

Set against a bass-heavy soundtrack, the film has an almost gameshow feel – like a race to grasp the hidden meaning. “With Adobe Stock Audio, you can add tracks layer by layer – the drums, the bass, the various instruments,” he says. “So I took the bass part of a track and sped it up, to create more tension. It keeps the focus up, makes it feel hypnotic.”

But most of all, Taylan hoped to use film, which has historically been a powerful catalyst for social change, to nod towards what our own future might look like. By framing The Bubble in the VHS format, he depicts these habits as dated ideas we are already moving away from; in the future, he suggests, anything is possible. “Maybe this will be the final drop,” he says. “The one that creates the flood.”

After all, at a time when audiences are consuming more film, more art, more music and more magazines than ever before, the creative community is in a position to reach more eyes and ears than it ever imagined.

Interruptions, however earth-shaking they might be, precipitate change – on both a global and an individual scale. This one has prompted makers around the world to look again at their processes, their messaging, their motivation and their perceived limitations. Because creativity is adapting and evolving all the time. And while it’s impossible to predict what might come next, you can be sure the world will be watching, rapt.

WePresent and Adobe Stock have partnered to highlight the Adobe Stock Film Festival, showcasing the creativity of 13 global filmmakers using the vast library of millions of royalty-free stock images, photos, video, vectors and illustrations from Adobe Stock. The films have been edited using Adobe Premiere Pro with music handpicked by the creators from Epidemic Sound. Want to create for yourself? Try both Adobe Stock and Adobe Premiere Pro for free, and find out more about the Adobe Stock Film Festival here.