For many creatives, like illustrators, designers and photographers, knowing what success looks like and when you’ve reached it, is hard to pinpoint. Madeleine Dore explores how creative minds deal with the pressures of becoming, being and staying successful.

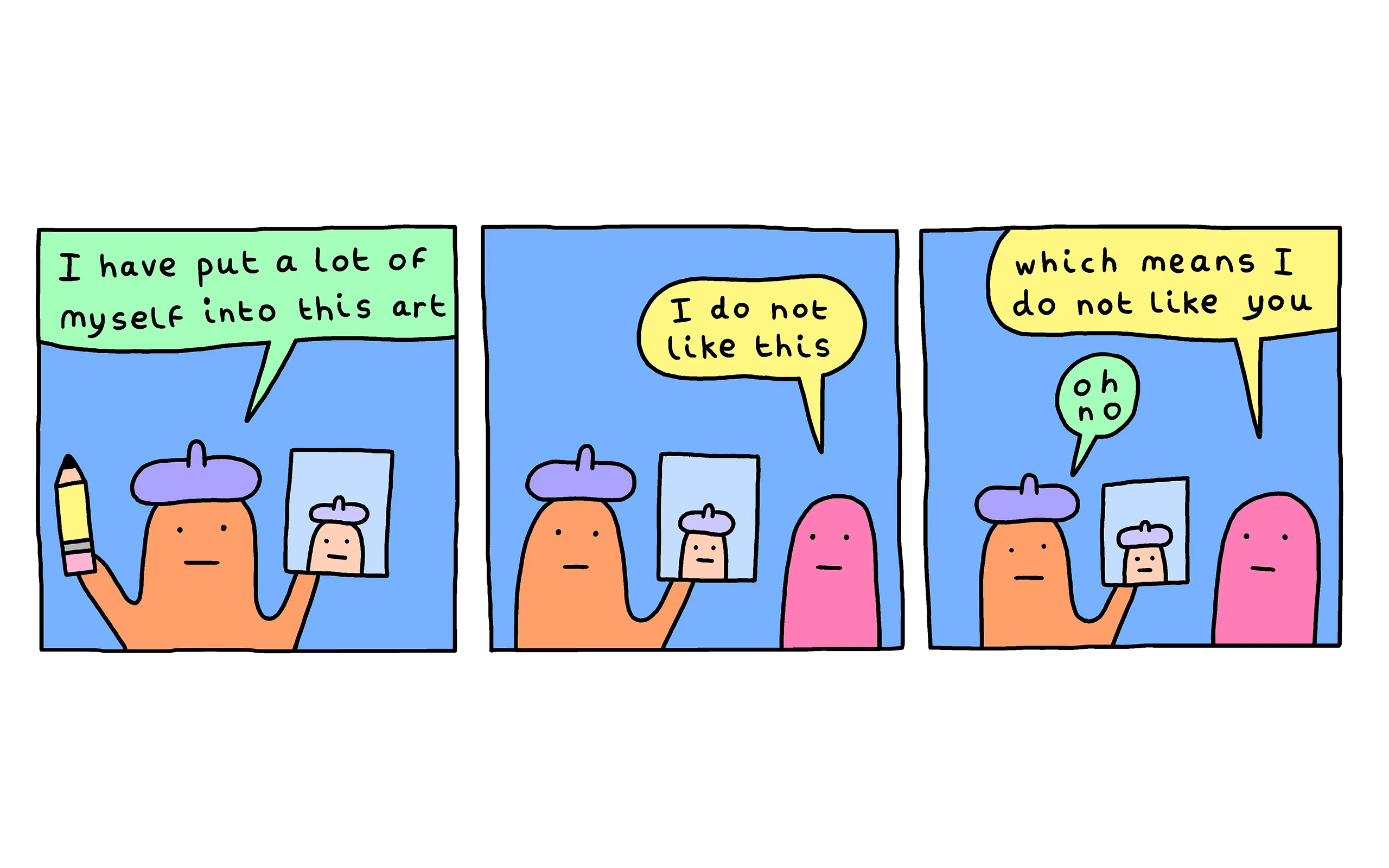

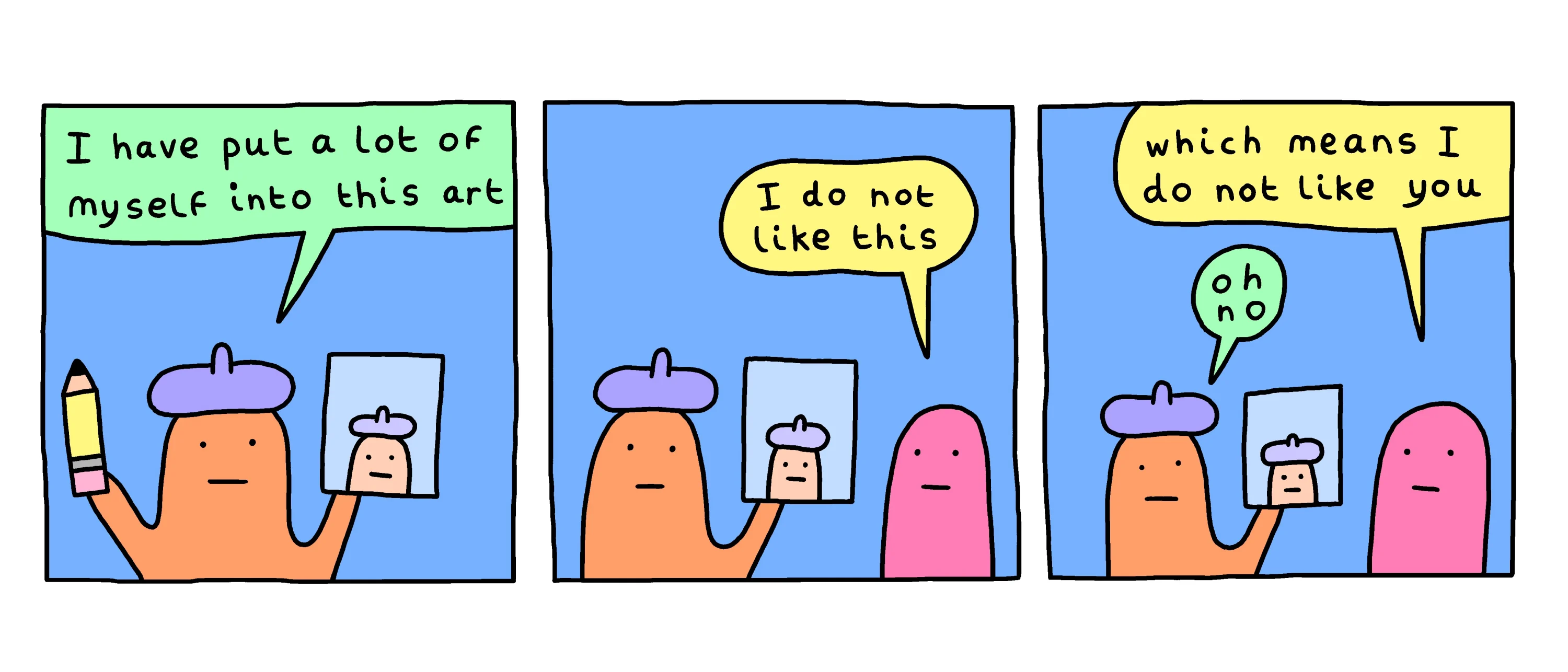

Illustrations by Alex Norris

As an artist have you made it when you’ve illustrated the cover of The New Yorker, or when you reach over 100k followers on Instagram? These are questions creatives have to grapple with throughout their careers.

Taking the creative path can make you feel uncertain about if or when success will come, with an implicit requirement to explore new ideas and territories bringing a series of ever-shifting goal posts.

As creative work is often tied to how artists find meaning in their lives, putting work into the world sometimes feels like putting part of yourself out there too – it’s very personal and intimate. As a result, striving for a successful creative career also means having to deal with judgement and rejection of your personal work, which can lead to stress and, at times, existential depression.

As Eric Maisel, author of The Van Gogh Blues: The Creative Person’s Path Through Depression somewhat bleakly put it: “The dirty little secret is that if you spend three years writing a novel you may end up with a successful novel and at that split second you may feel like you’ve done something meaningful, but for those thousand days virtually 700 or 800 of those days you are just slogging along… most of the time you are not experiencing life as successful or meaningful.”

So how do independent creatives deal with day to day “slogging along”, without knowing when or how it will add up to a successful career?

One way to do it is to look at textbook measures of success, like fame, wealth and social status. These can act as a springboard for creatives to define what a successful career means to them – even if it takes a few wrong turns in the beginning.

This rings true for artist, illustrator and speaker Mr Bingo. For the first decade of his career in animation, publishing and advertising, his idea of success was, “probably recognition, being perceived as successful by others, and possibly some sort of riches as well.”

I decided that busy meant that you had lost control of your time and freedom, which is not something I want.

Working for clients like The New Yorker, The Guardian, The Mighty Boosh and more, by Mr Bingo’s own definition, he had attained success.

Yet despite reaching the pinnacle, there was a feeling of emptiness. In 2015, Mr Bingo decided to ditch the illustrious commercial work to focus on his independent art practice and redefine success as “being free and happy in life.”

Adjusting his definition of success has seen Mr Bingo make other pivots in his recent career, such as deciding he wasn’t busy, a rebellion against the common narrative that busyness is a badge of honor.

“I decided that busy meant that you had lost control of your time and freedom, which is not something I want. Being busy sounds like you are beholden to other people’s demands, people that you’re working with or for. I stopped working for clients three years ago, so if I’m busy, it’s totally my own doing, nobody is asking me to be busy.”

This is something New York Times best-selling author and illustrator Mari Andrew is learning along the way as well. “When I was 21, my understanding of success could be boiled down to numbers: how much money I had, how many goals I had crossed off, how many close friends I had,” she says.

Ten years later the numbers have arrived for Mari, but instead of making her feel like she has reached success and could reap the rewards, an Instagram following of over 850,000 has created more pressure to perform, numbers-wise.

She’s now learning to focus on how she is feeling in her work, rather than the numbers, to look at her creative successes differently. “Now my metric of success is all about feeling: How alive do I feel? How much newness am I infusing into my daily life? What adventure will I take next? Is this fun?,” she says. “I am constantly seeking new ways to learn and delight myself. Otherwise, what's the point?”

With a lack of clear trajectories to follow or universal indicators of success, we tend to look at our peers and judge how they are performing compared to ourselves. Do they receive more likes, have they got more followers? Do they get to work with that client you’ve wanted to work with for forever?

Essentially, if you work hard and you do good work, then the success will hopefully follow.

Social media may amplify this tendency to compare, but it’s not a new phenomenon. Our brains are wired to figure out where we sit in the social pecking order and when we feel our status may have dropped or be threatened, we feel deflated.

Not only can this game of comparison feel like a demoralizing rollercoaster, it’s also inaccurate. When we are only privy to other people’s highlight reels, we can easily discount our own experiences, skills and achievements.

This distorts our view of ourselves and others, but it can also stifle our creative ideas. Multidisciplinary designer and artist Beci Orpin can sympathize with the difficulty young or emerging creatives face now with such explicit measures of success inherent to social media.

“Early in my career I put a bunch of energy into being jealous of my peers. Even though I was having my own successes, in my eyes it paled in comparison to what they were experiencing at a similar stage of their careers,” she says.

My metric of success is all about feeling: How alive do I feel? What adventure will I take next? Is this fun?

“I feel like it's really hard now with social media because there is this literal measure of success that can be both distracting and discouraging. But, essentially, if you work hard and you do good work, then the success will hopefully follow.”

When she stopped putting energy into comparison, Beci freed the energy for her own work and was able to inch towards her own version of success. “Once I stopped worrying about what other people were doing, that energy was redirected and I started to focus on what I was doing and worked hard towards that.”

This shift allowed Beci to use her skills to help bring others up the ladder of success with her. She’s now known to be a great mentor to young Australian designers and artists. For her it’s a way to make a difference and help people find their own energy and momentum.

“The work I do is essentially just making things look nice as a designer. Of course there are designers who create things that do change people's lives, but I’m not one of them,” she says. “But what I can do is make the world better by sharing ideas, passing on what I have learned so people can take that and have a positive influence that way by promoting anybody who feels like they are going to find it harder to get somewhere.”

Although they have figured out how to define success for themselves, it doesn’t mean Mr Bingo, Mari and Beci always feel they’ve “made it.”

“Sometimes I’ll be sipping champagne on a business class flight to a conference to be paid to tell people about my life, which in some ways does feel like I’ve made it,” Mr Bingo says. “But just before I go on stage at said conference, I’m hit with imposter syndrome and think I’ve done nothing, I am nobody, and I’m there by mistake.”

You can never make it, you’re just constantly striving to be better and make something new

Our views of our creative work can resemble a Newton’s cradle, the pendulum swinging from assured confidence, to feeling like a complete intruder into a world you know nothing about. But perhaps it’s that swing that motivates creatives to strive for success.

“As a creative person, all you’re really motivated by is making new things and getting new reactions from people, so you can never make it, you’re just constantly striving to be better and make something new,” Mr Bingo adds.

Without striving to do new things, we would be left with complacency, Beci says. “It’s really easy to rest on your laurels and keep doing the same thing – especially as you get older – but I think that’s stifling for creativity.”

The minute you think you’ve arrived is the minute that everything crumbles.

Getting outside your comfort zone is key. “You have to keep pushing yourself forward and trying new things – and that doesn’t necessarily have to be creative, it could be something like public speaking.”

There is a fine balance between striving to do new things and appreciating what you have achieved. For Mari, remembering all creative work is a process helps to find that equilibrium. “I think I've ‘made it’ in that I have people who want to hear what I have to say – what a dream – but I know it could go away at any moment,” she says.

“I am so grateful for where I am, but life is fluid, surprising, strange, and much bigger than we could ever imagine. The minute you think you've arrived is the minute that everything crumbles and you have to rebuild.”