Imagine a place where people who don’t often get all the chances in life that they should can express themselves without any limitations. A place where they can paint, sculpt, draw, do wood-work, or any other creative endeavor that captures their imagination.

This is exactly what happens at the Creative Growth Art Center, the world’s oldest institute for artists with developmental, mental and physical disabilities. Director Tom di Maria, who’s been part of the program for 17 years, still vividly remembers his first encounter with the the Oakland-based center.

“When I walked into the studio where the artists work, it was so compelling for me to see the process they were engaged in. I realized there was something really magnificent about what art is, and what art tells us about the human experience,” Tom says.

The center is based in a large industrial building, and most of the activities take place in the same space. They work with 160 artists, of whom about 100 visit the studio every day. The artists don’t have to pay for their spot, they get all the materials they need and the place is their’s for as long as they want it. There are no production deadlines, no passing or failing and no grading.

Creative Growth’s philosophy is not to teach, but to expose artists to materials, so they can explore their own style without pressure. “If you look at the people who come, often they’ve been told in their life to be quiet, to take up the least space possible. Here we say, ‘Tell us everything. Take as much space as possible. Take as much time as possible.’ And if you open the door like that, people walk through it,” Tom says.

And even though they do things a little differently from traditional academic programs, it doesn’t mean they aren’t taken seriously by the art world. In fact the center’s artists have been shown in an impressive collection of museums and art fairs, such as the MoMA, theSmithsonian Institute and Art Basel.

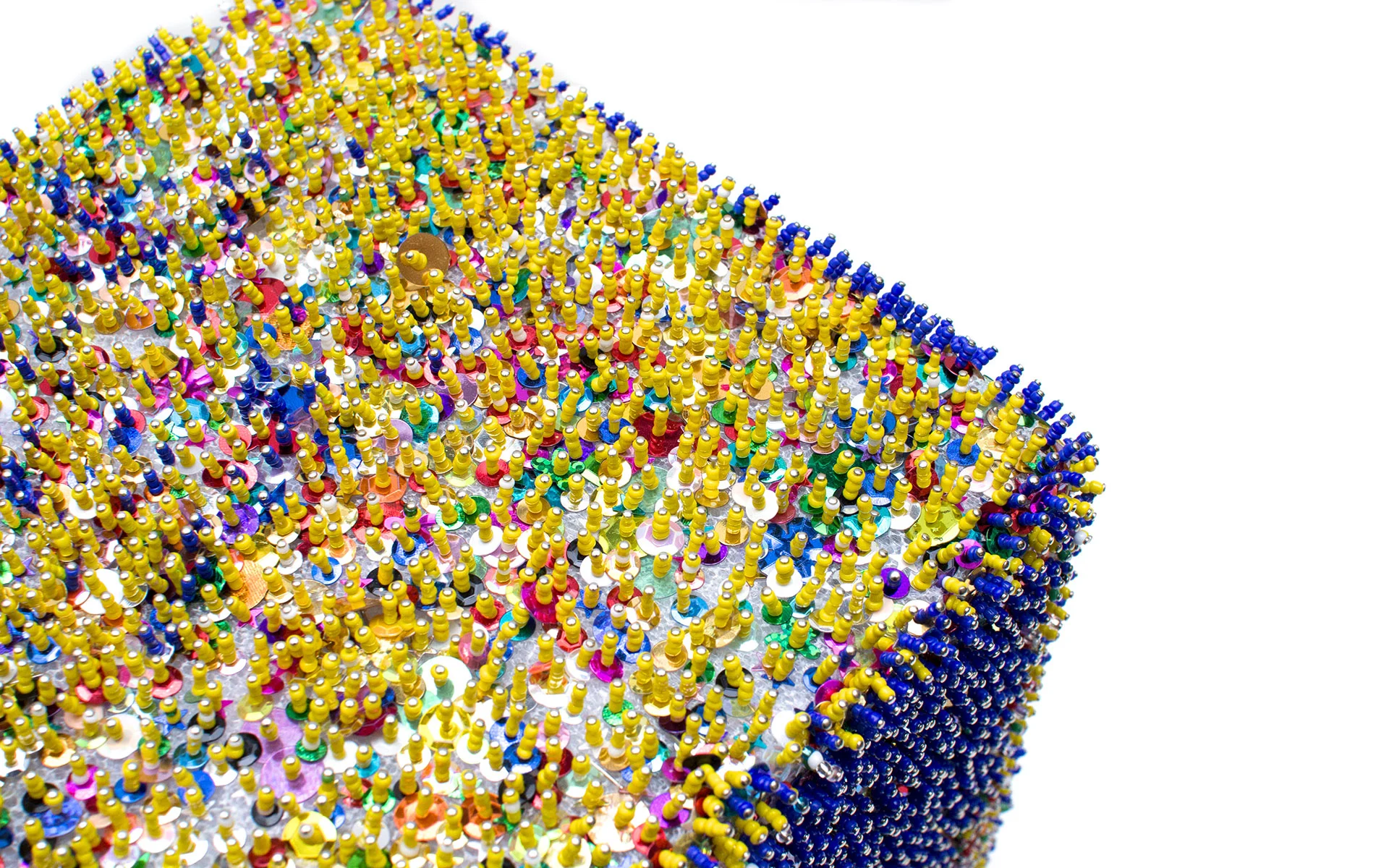

Judith Scott, for example, is showcasing her work at this year’s Venice Biennale as one of the first artists with developmental disabilities to be represented at the festival. “She was isolated in an institution for most of her life and wasn’t used to expressing herself; we might have lost her entire life’s career if we were in a hurry,” Tom says. It was two years before she started making artworks at the center, but she hasn’t looked back since.

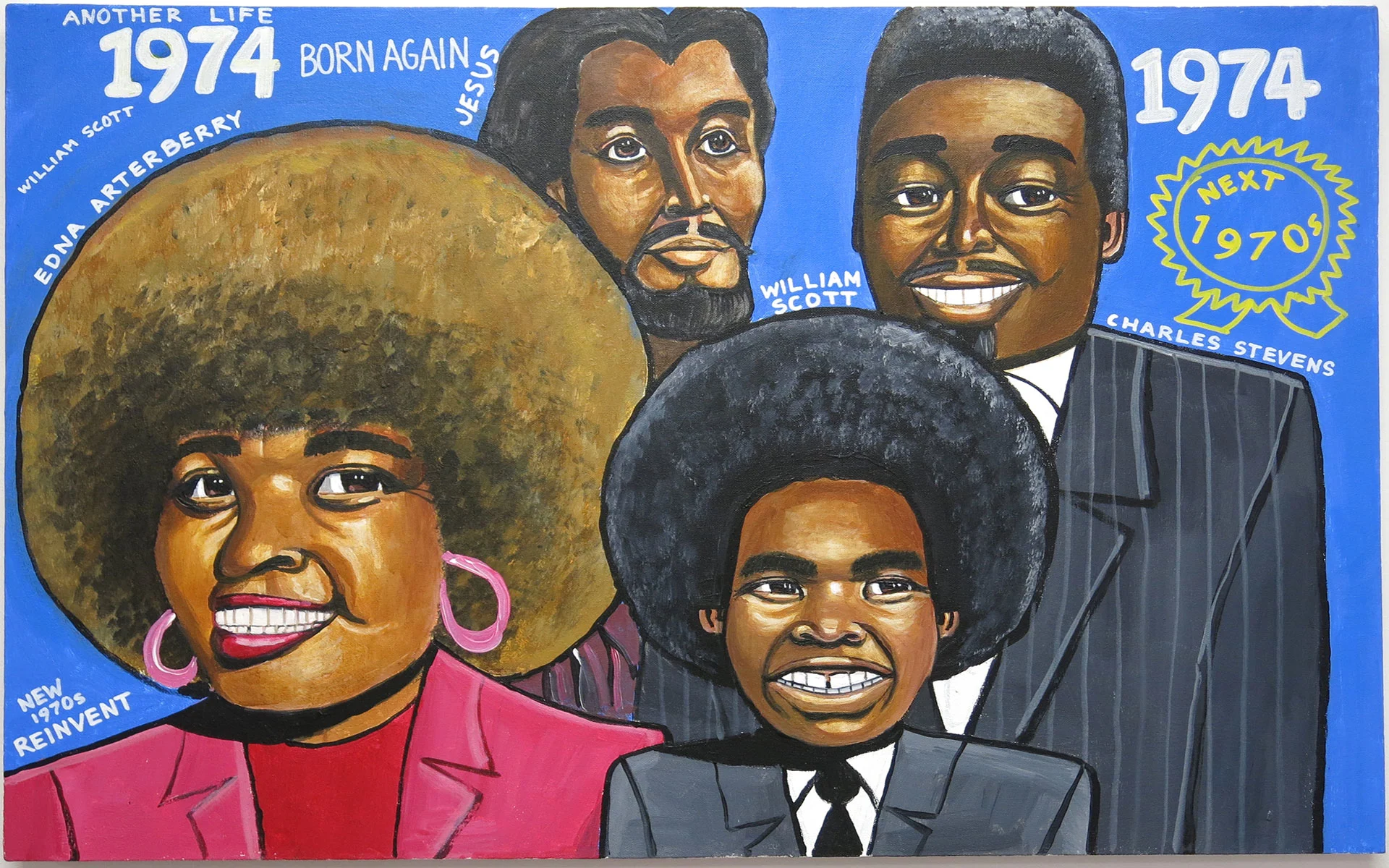

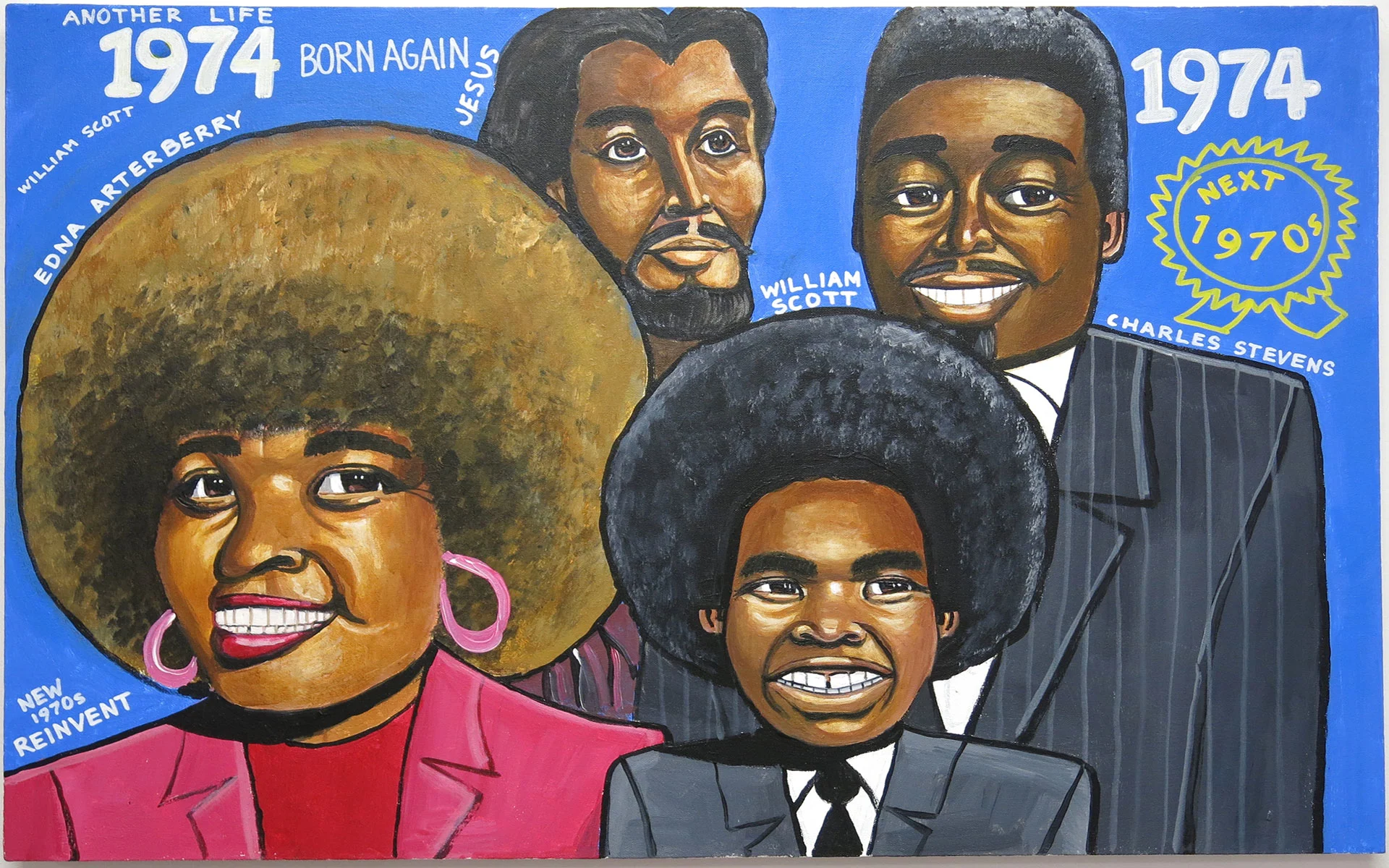

Whereas the traditional art scene usually responds to trends, movements, and the commercial market, the artists at Creative Growth aren’t affected by these influences – they are completely free to create.

“I think what makes the work of our artists so interesting is that it doesn’t respond to art history. It’s not rejecting an art movement, and it’s not about accepting another artist’s work. It’s about doing your own thing.”

For the people who run the center, the most inspirational thing is the energy and enthusiasm of the attendees.

“What I love is the artists’ absolute joy in art-making. How they bring this fresh perspective to it every day, how they work tirelessly, how creative it is.

“There is an essential need for people with disabilities to express themselves, to be able to become artists, and tell us their stories,” Tom says. “In a perfect world, Creative Growth is gone, because everyone would have access. But until that time, we try our best to make art equal for everyone.”