Cinga Samson’s project, Iyabanda Intsimbi / The metal is cold, is a study on the nature of violence. Not necessarily human violence, but the threats we face on a daily basis, be they from nature, chance, or the passage of time. Here, he tells Allyssia Alleyne why the idea was born as he faced misfortune in his own life, and how he went about translating something that seems so random and indefinable onto canvas.

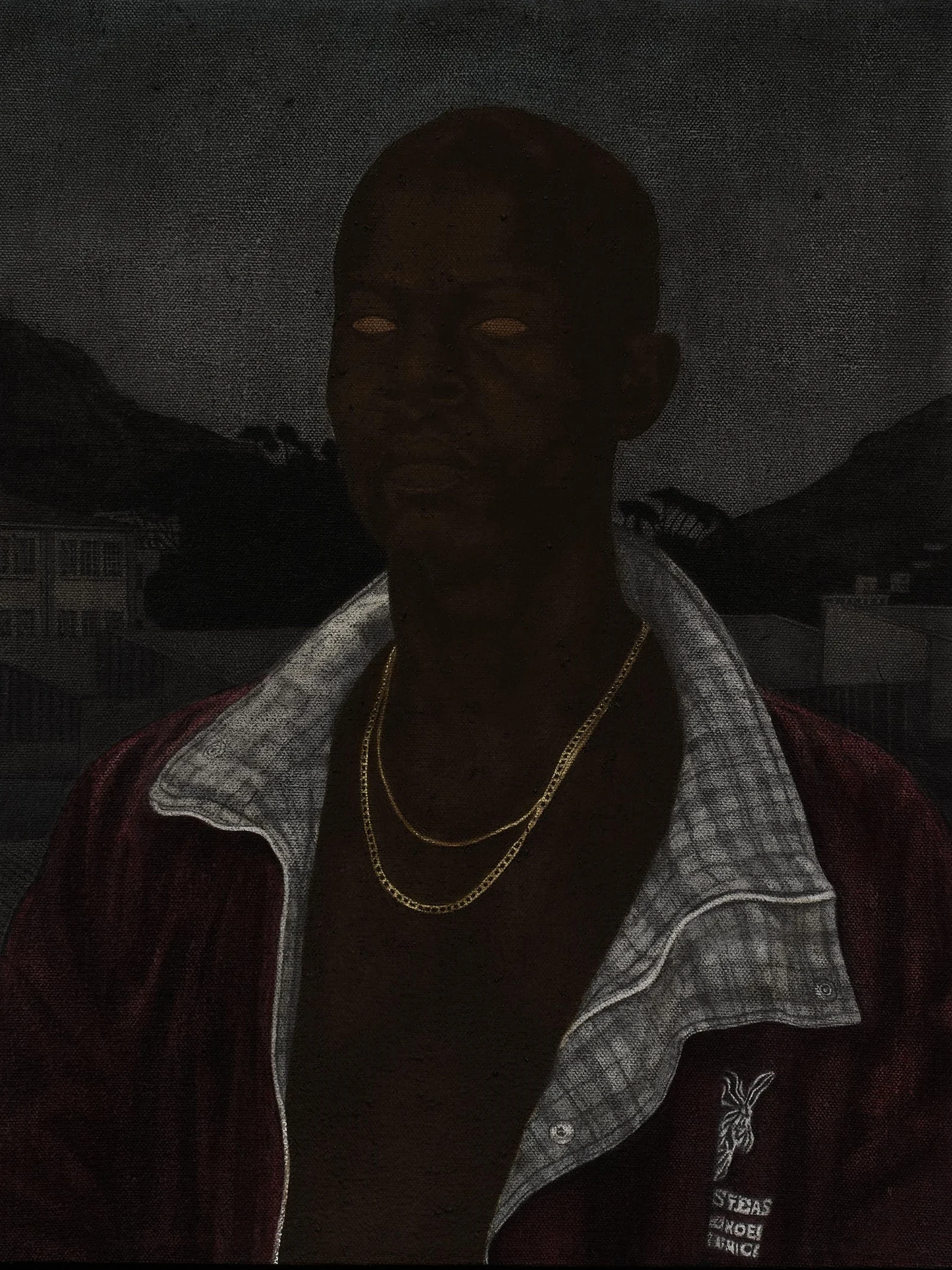

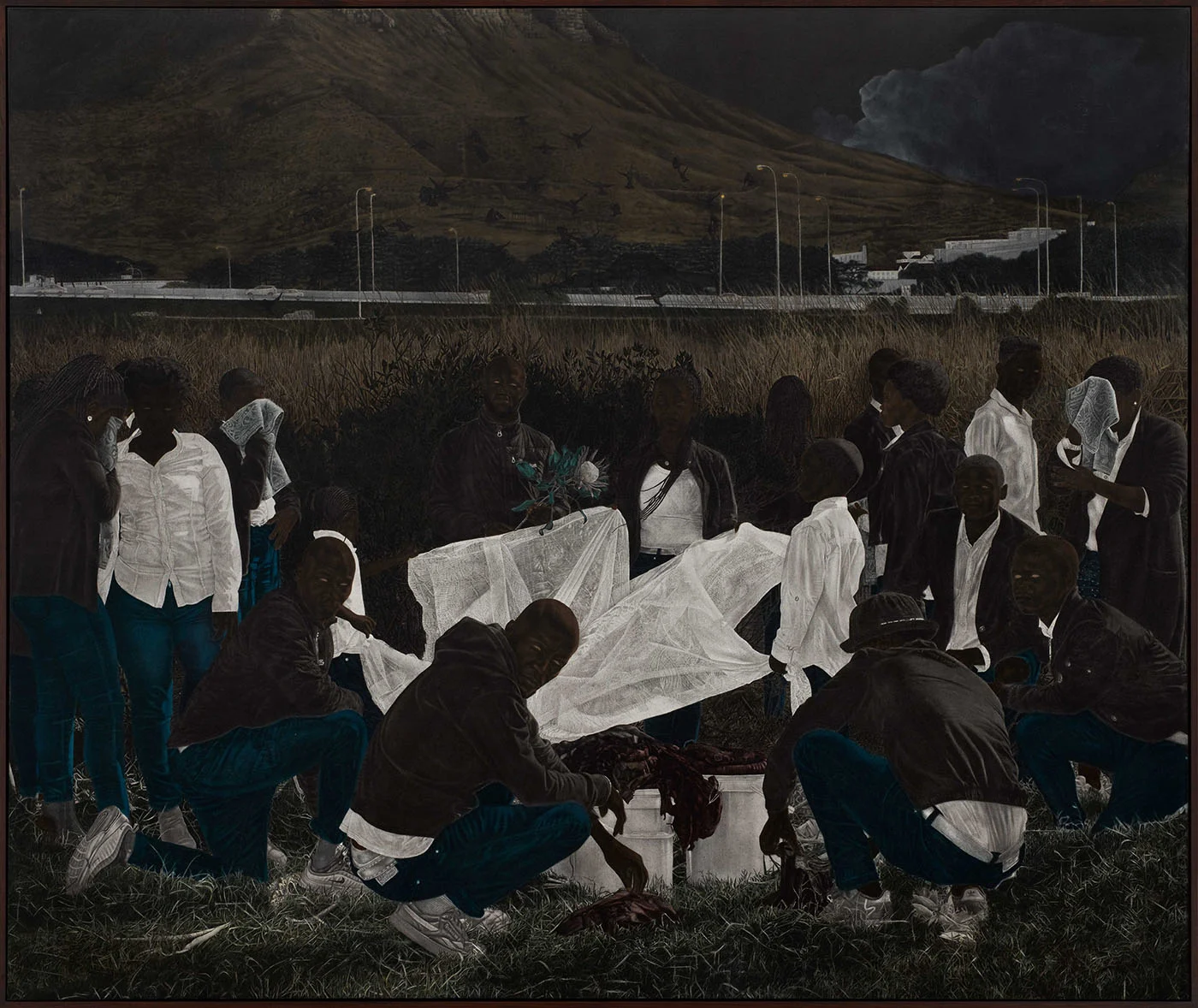

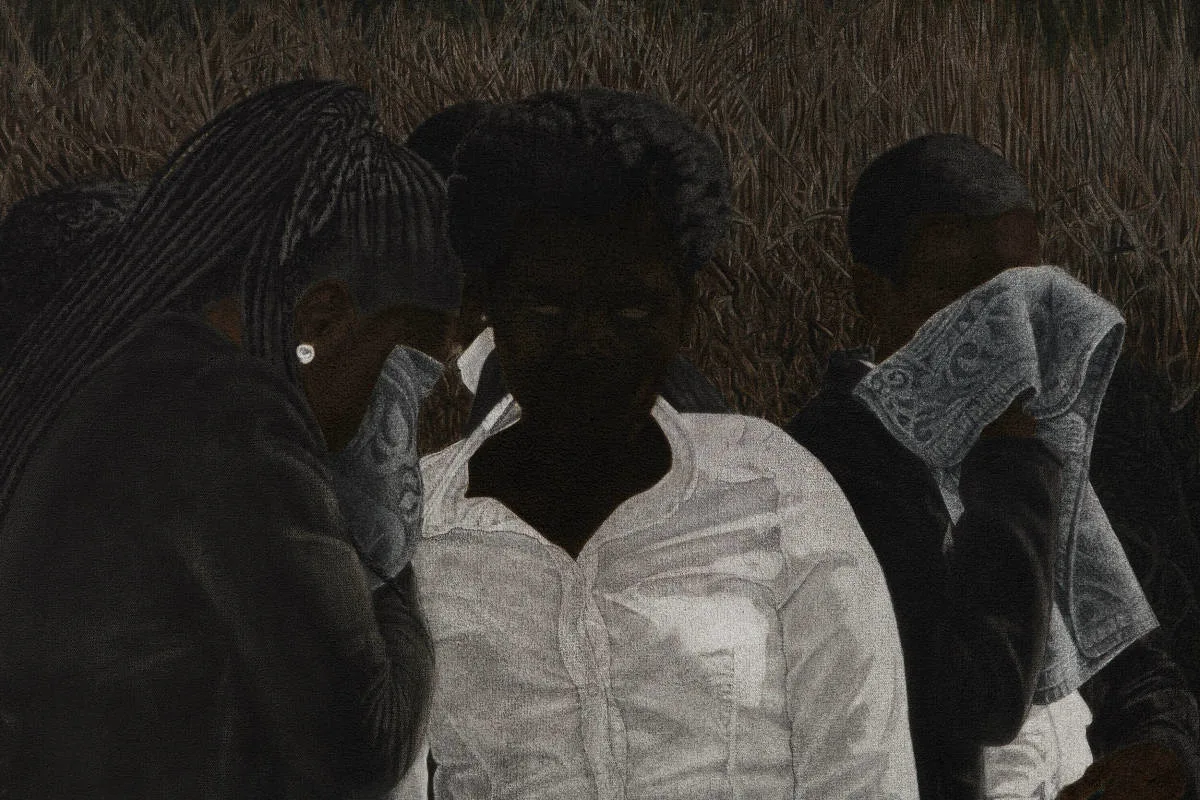

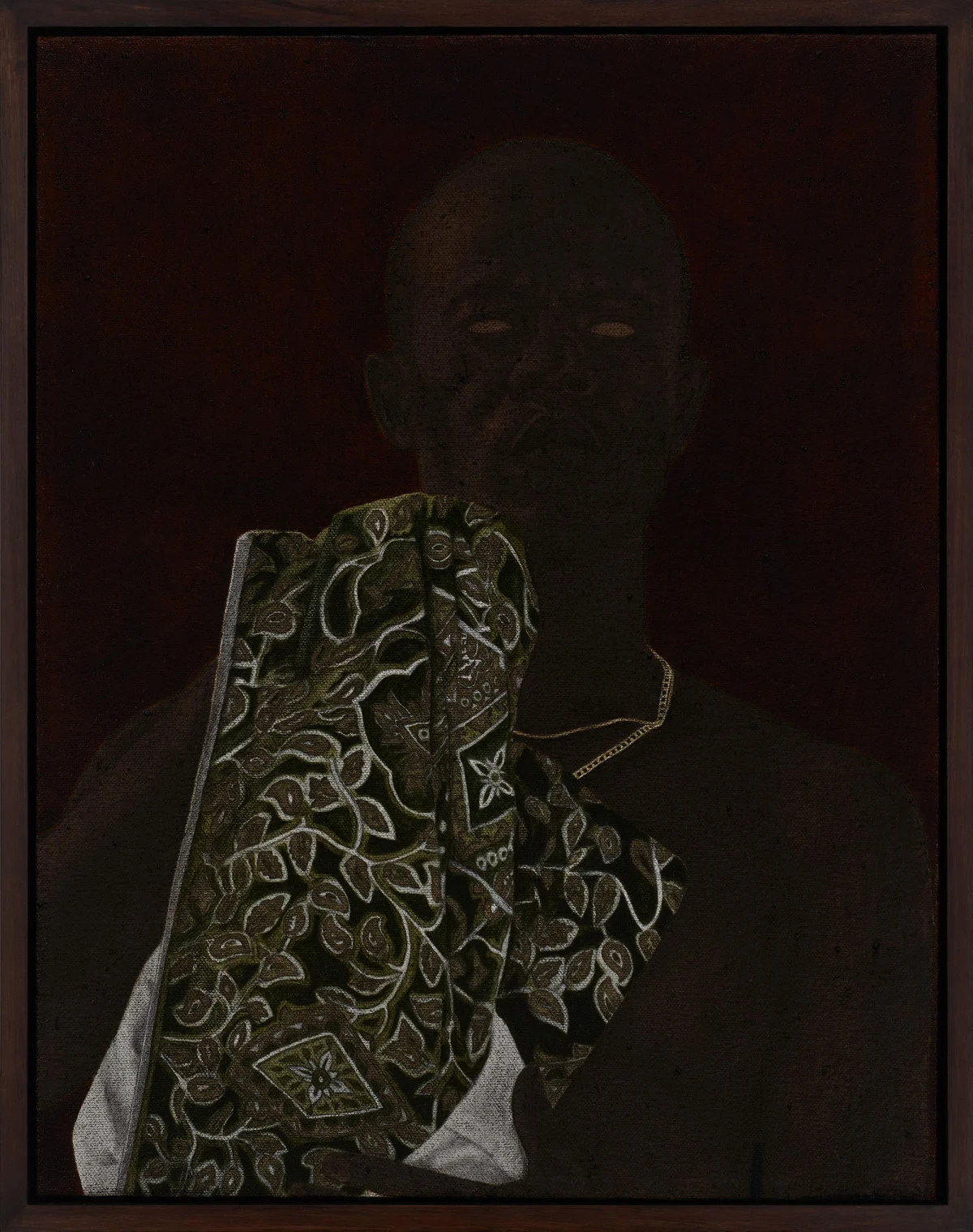

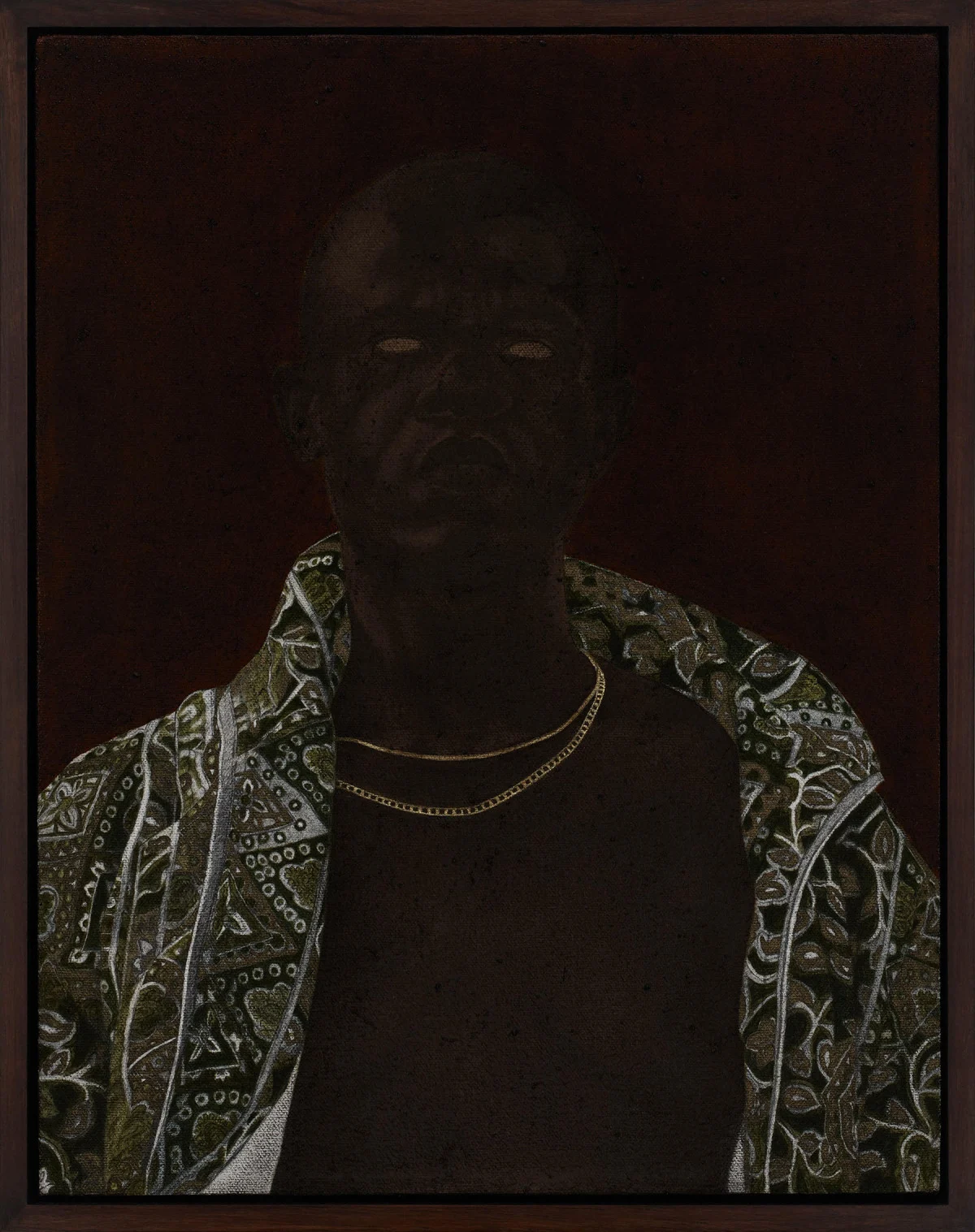

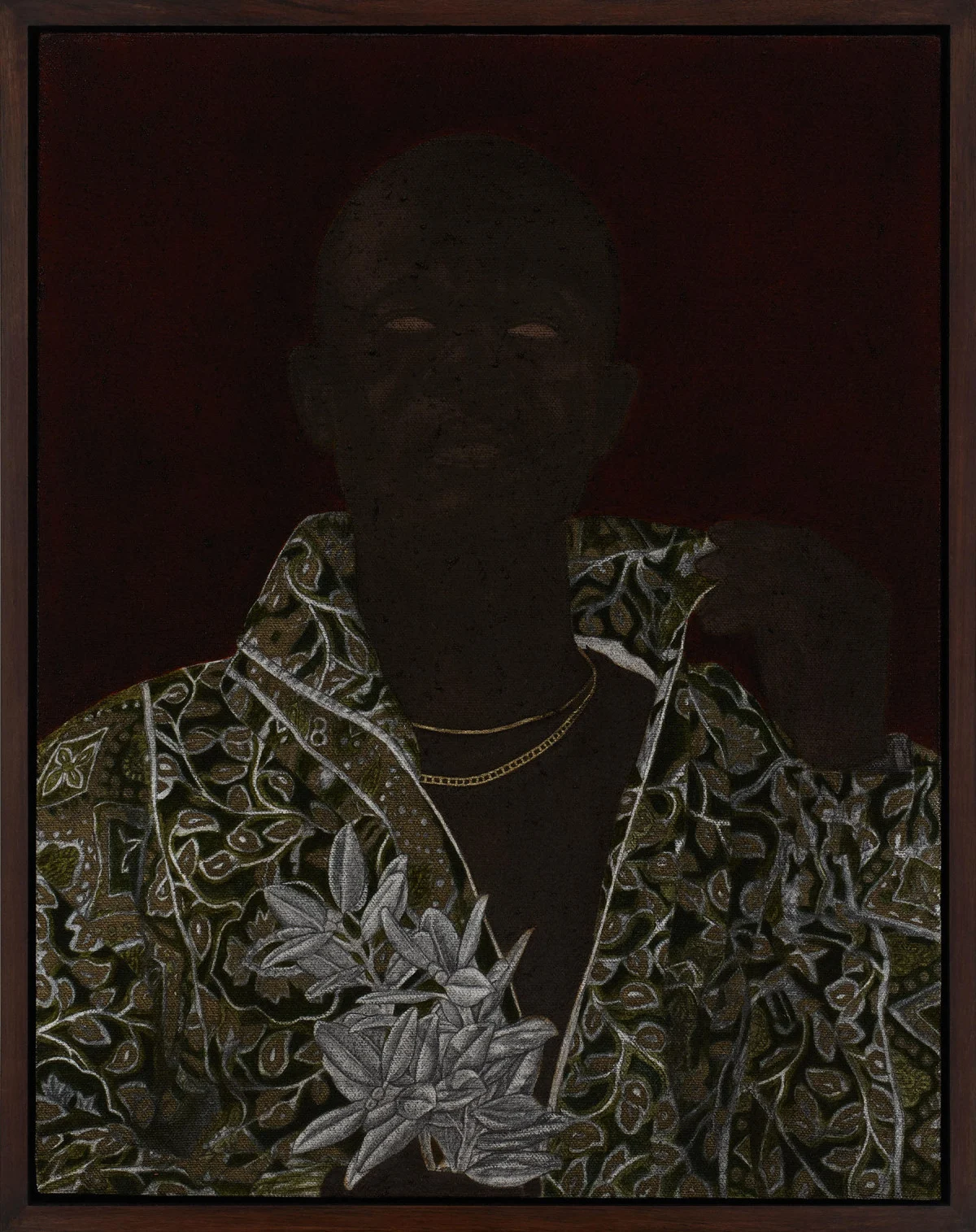

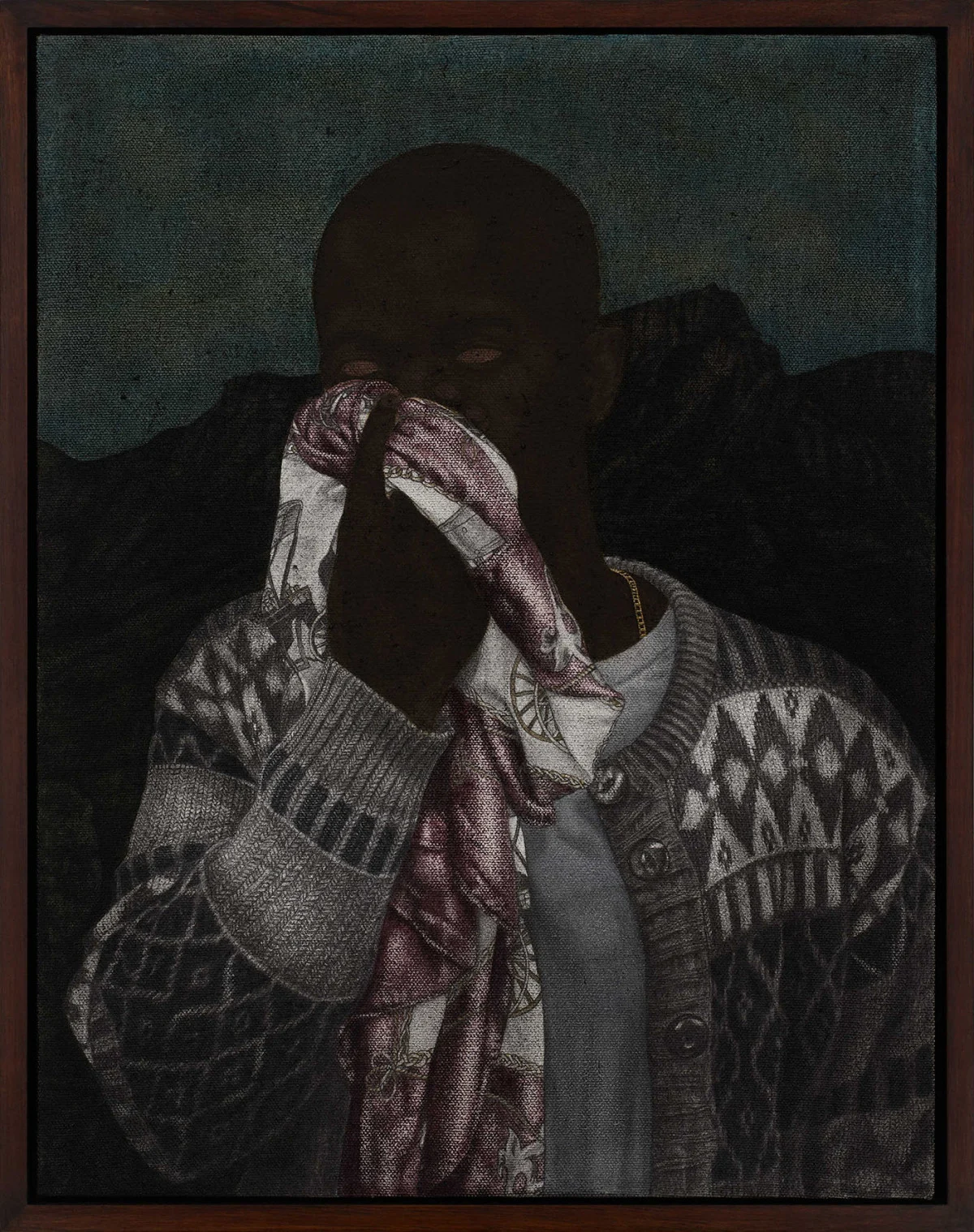

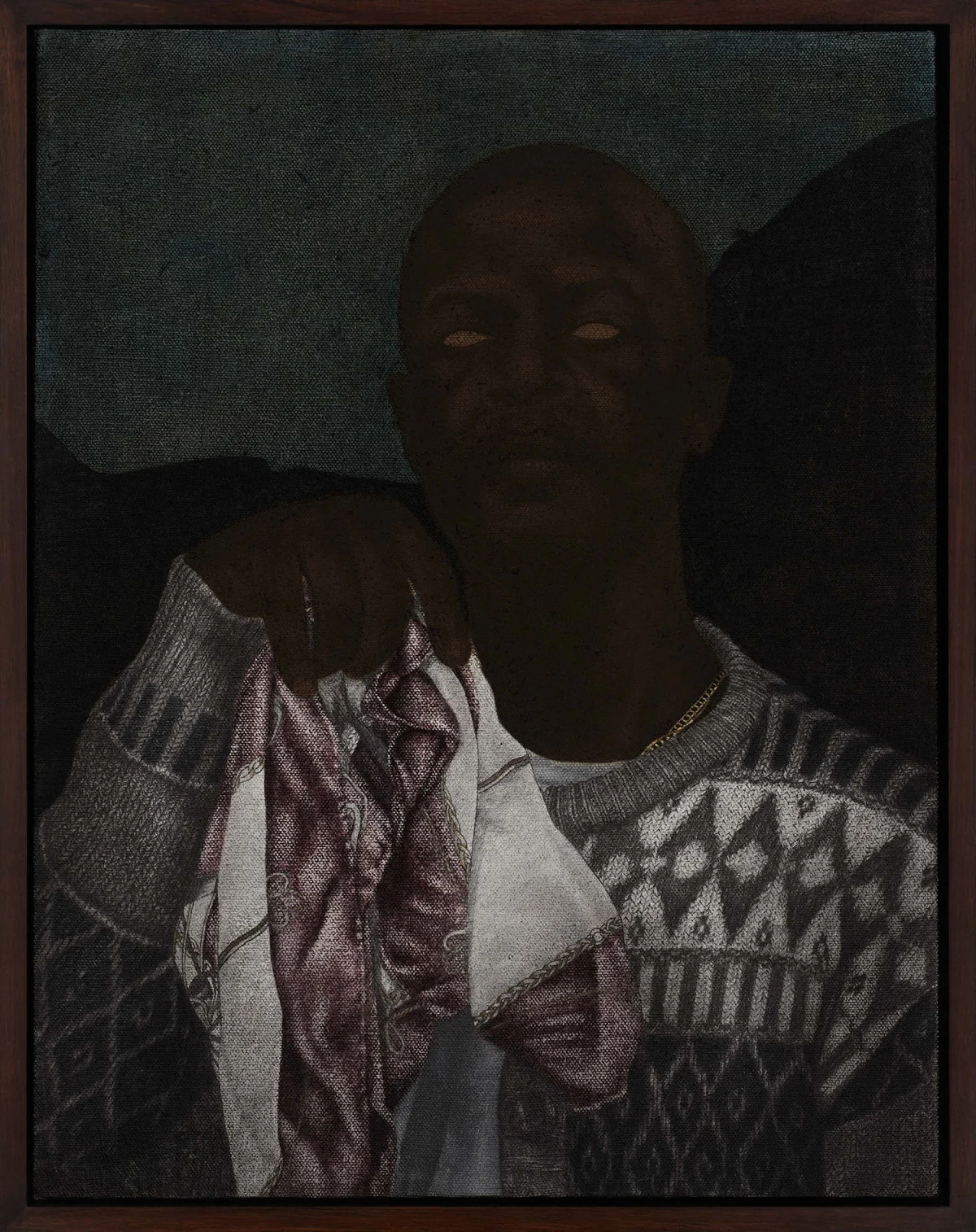

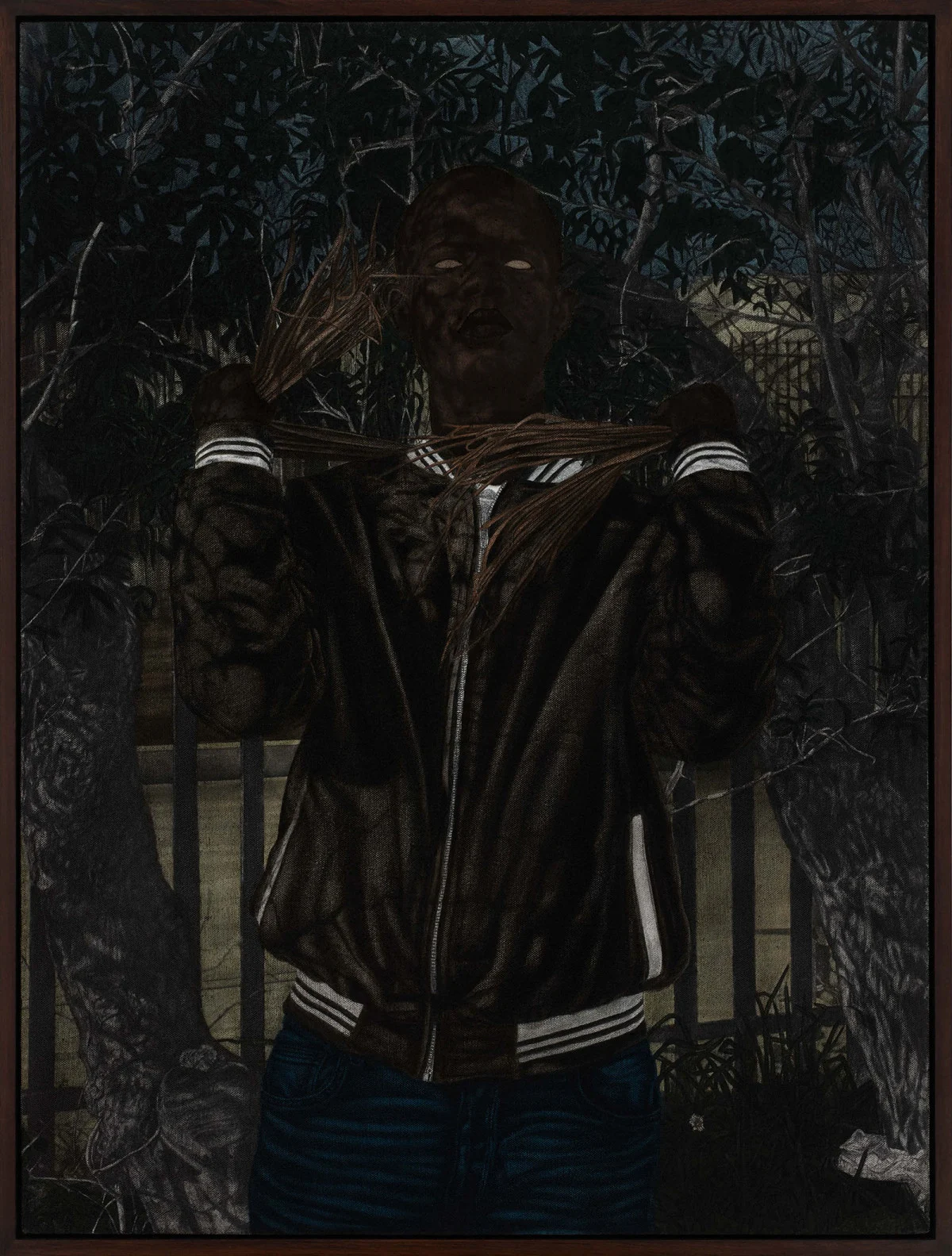

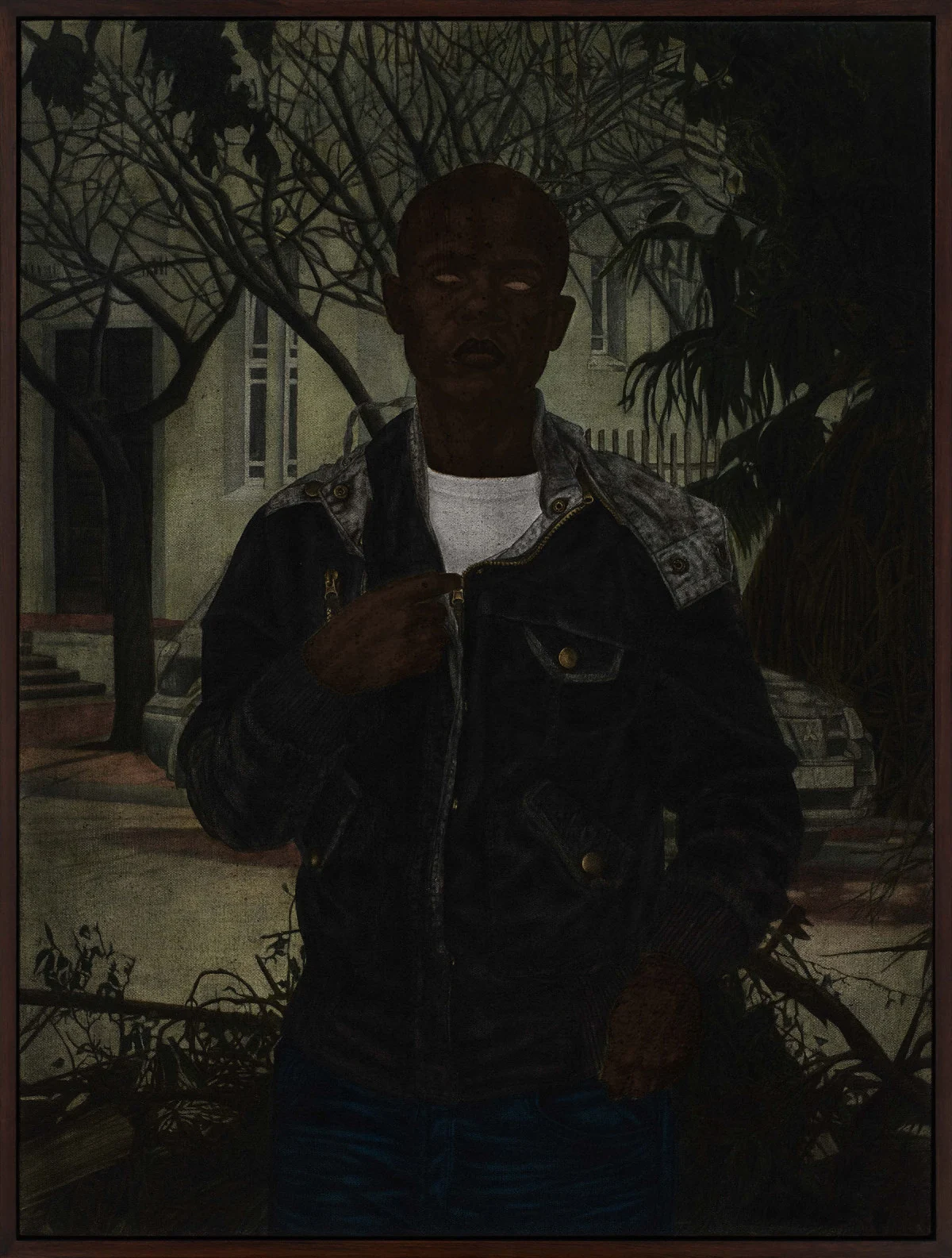

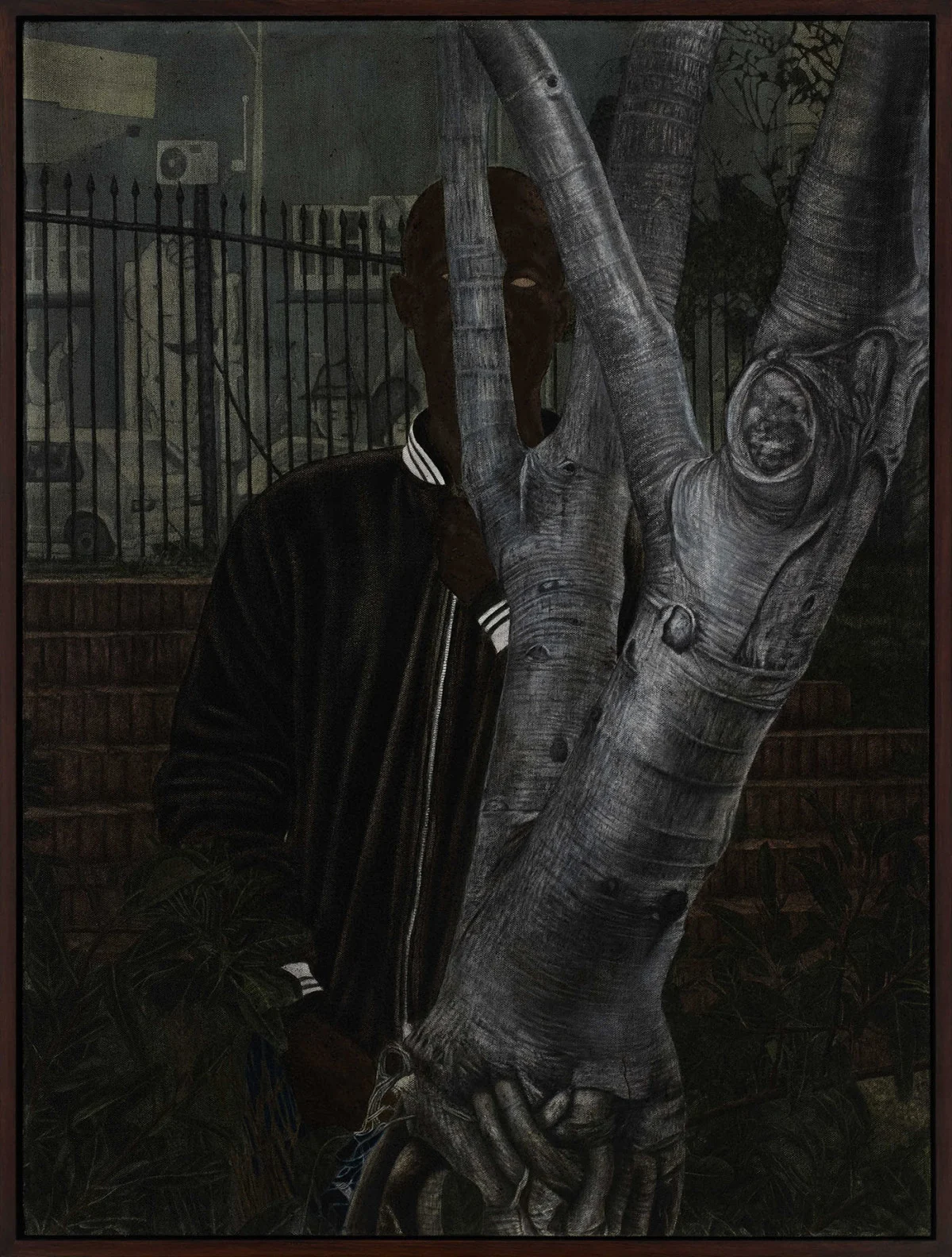

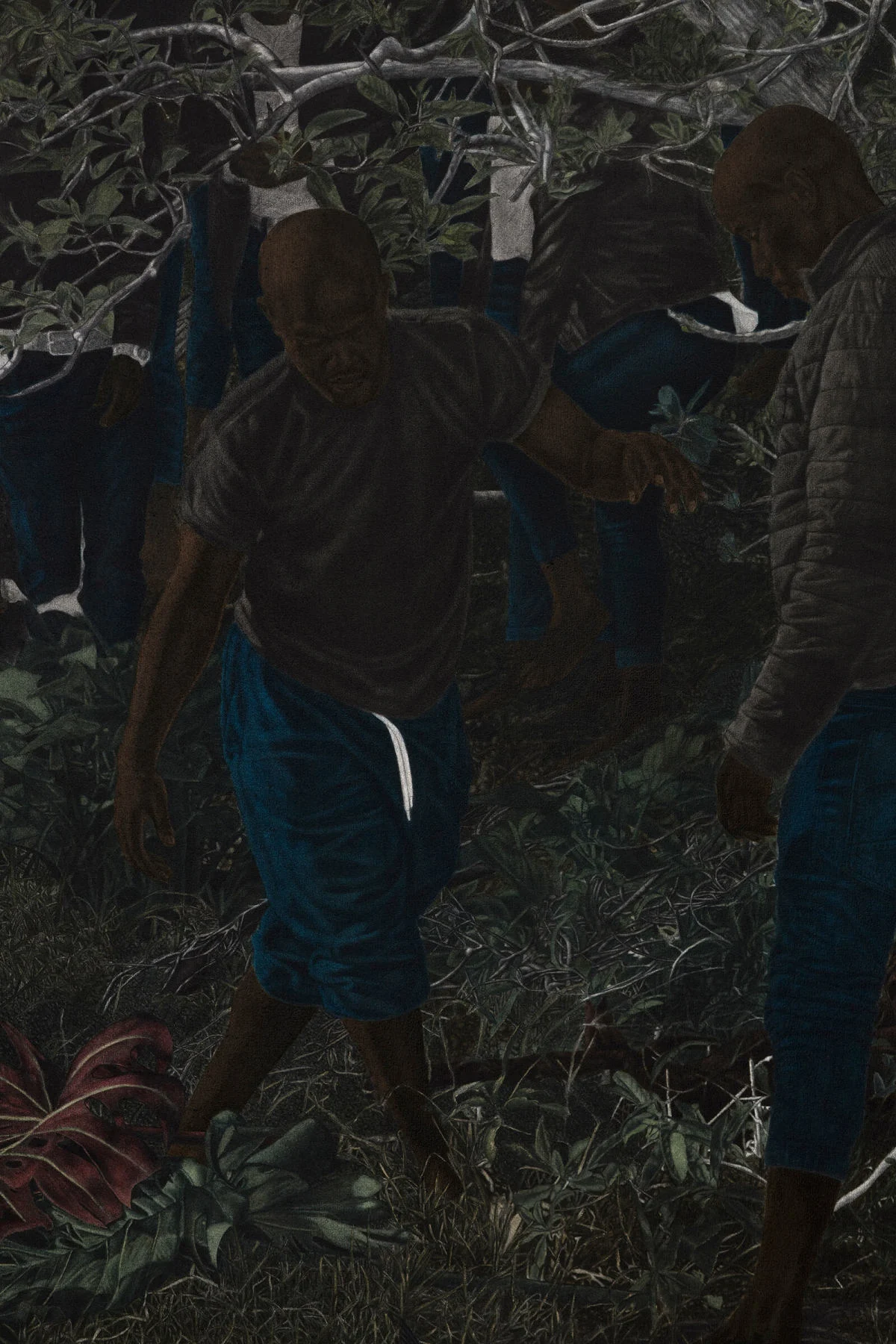

There’s something unsettling at the heart of Iyabanda Intsimbi / The metal is cold, a show of 26 new paintings by the South African artist Cinga Samson at the FLAG Art Foundation in New York. Group scenes and portraits set around Cape Town are painted in a palette of oils so dark that, in some lights, his figures are almost indistinguishable from the verdant landscapes they inhabit. Often, it’s only the white that cuts through on sweaters, sneakers, tangles of branches, and pupil-less eyes—a signature of the artist—that meet the viewer with unwavering intensity.

On the foundation’s website, Samson calls the work an exploration of “the nature of violence: its laws, its flair, and its finality.” But when we speak just days before the exhibition’s mid-October opening, he feels the need to clarify: To describe his subject as “violence” is something of an oversimplification. “For lack of words, I want to say it’s violence, but it’s not,” he explains during a video call from his studio in Cape Town. “It’s part of how things are structured, a necessity to maintain balance—if there’s such a thing.”

This “it” is not interpersonal brutalities per se. Instead, the artist is referring to the inescapable threat of demise or destruction that lurks beneath the surface of daily life. Personal suffering and death, he elaborates, are just one part of that essential reality. “And it’s not just human beings that are subjected to it,” he says. “You can broaden it up to space: Stars collide, new stars are born, others are destroyed… A black hole swallows another black hole, and then everything it comes across.”

For Iyabanda Intsimbi / The metal is cold, Samson set out to imbue his paintings with the uneasy energy he associates with this persistent, dispassionate threat. In the titular metaphor, he likens its presence to the chill of cold metal against skin.

The series is mostly paintings of individual men, violence incarnate. Decked out in gold chains and in clothes covered with ornate patterns, they clutch cut plants and cloth, obscure themselves behind branches—actions that appear benign, but beg for interpretation. Their glowing eyes meet the viewer, implicating them in the moment they’ve stumbled upon, even if they don’t quite understand it.

I want to say it’s violence, but it’s not. It’s part of how things are structured, a necessity to maintain balance.

But the showpieces are the three large-scale group scenes. In one, men seem to circle a large leaf that has fallen in the forest “like a pack of hyenas about to eat that impala or springbok they’ve surrounded,” he explains—a subtle nod to the threat man poses to nature. But the others are harder to decipher: Guests gather next to a highway for a ceremony that seems at once marital and funereal, involving buckets of animal flesh, a wide white veil, and a stone-faced couple; a group of young people seem oblivious to a lone figure lying prone on the grass among them, focusing on a man in a fur coat clutching an animal skull.

In each work, there’s a primal sense that something is not right, though the artist was intentional about avoiding definitive narratives and heavy-handed symbolism; uncertainty is a part of the invisible threat he was hoping to evoke. There’s the implication of violence or danger, pending or past, but that unease is provoked primarily by the layers of texture and darkness with which Samson paints his scenes, and in the ambiguity of his players’ actions. “The challenge in doing works like this is that everyone wants something literal,” he says. “But what’s more interesting is the experience of viewing the painting—what are you feeling?”

Samson first conceived of the series in 2020, in the wake of the pandemic, but the motive behind it was planted long ago. He traces his first ponderings back to a formative childhood experience. While playing in a cemetery with friends, he recalls witnessing a man stabbing another to death. While he considered investigating “this violence that is there within life” earlier in his career, he says: “I didn’t feel that I could articulate it well… I felt I was too shallow to have such a conversation.”

In 2020, the subject was urgent. Samson began to note those patterns of misfortune which appear throughout life. A solo show in New York shut just three weeks into what was meant to be a two-month run due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Shortly after his return from New York, Samson took a trip to the Eastern Cape to see his family after his show. His appearance, however, led to a fight between he and his brothers marked by serious outbursts of violence and aggression. On his return to Cape Town, feeling betrayed and confused, he was diagnosed with COVID-19.

Stars collide, new stars are born, others are destroyed… A black hole swallows another black hole, and then everything it comes across.

In January 2021, Samson also lost his father. “I felt violated because I didn’t cause any of these things. I felt some strong, ruthless hand intruding into my life, but I couldn’t point out where it is, or what it is. It’s just there. And then somehow, it made me think of all the circumstances where life has done that to me,” he says. “[To create this series] I needed a charge from inside. Once I got that charge… I knew I could put that [feeling] onto canvas.”

In the apparent randomness and universality with which violence is meted out, Samson detected a kind of spiritual order. As he reflected on his own experiences and discussed similar incidents with others, he was struck by the ordinariness of suffering. He was not the only one to have opportunities denied, fall ill, or lose a loved one.

After more than a year spent meditating on the nature of violence, Samson still doesn’t feel he has any further insights into its spiritual purpose, or the best way to manage the feelings it arouses. But ultimately, Iyabanda Intsimbi was less about making a point than capturing a feeling.

“This isn’t an exhibition where I have answers. I just want to give a small glimpse of this thing,” he says. “It’s just a single poem, nothing extra. I want [the viewer] to receive the poetry, and if they connect with it, fantastic.”