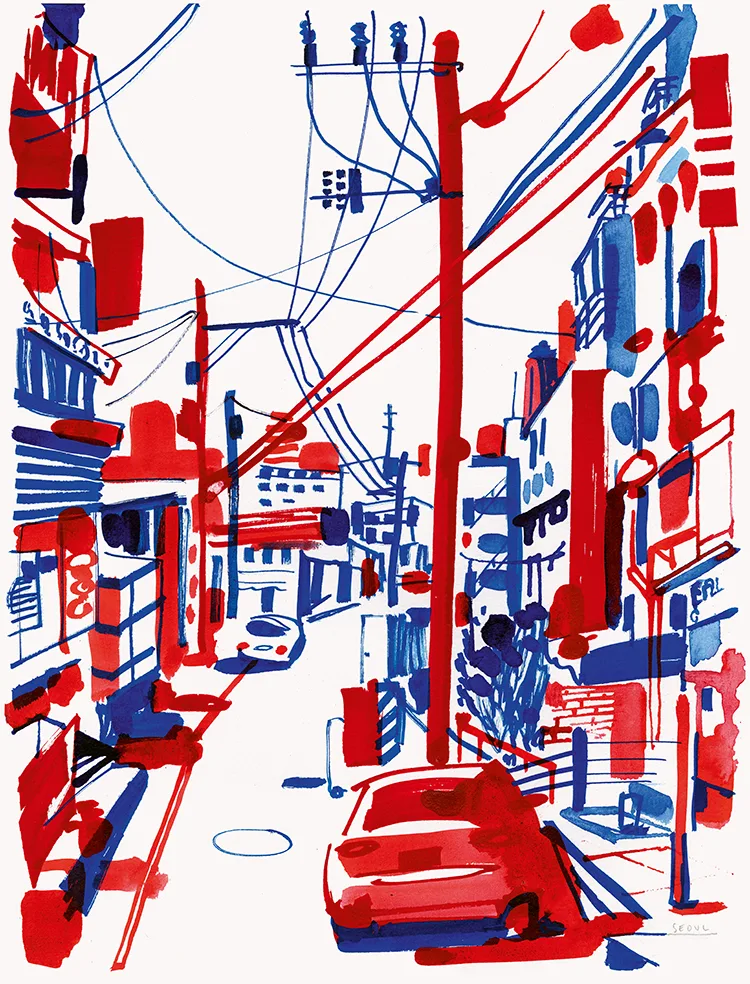

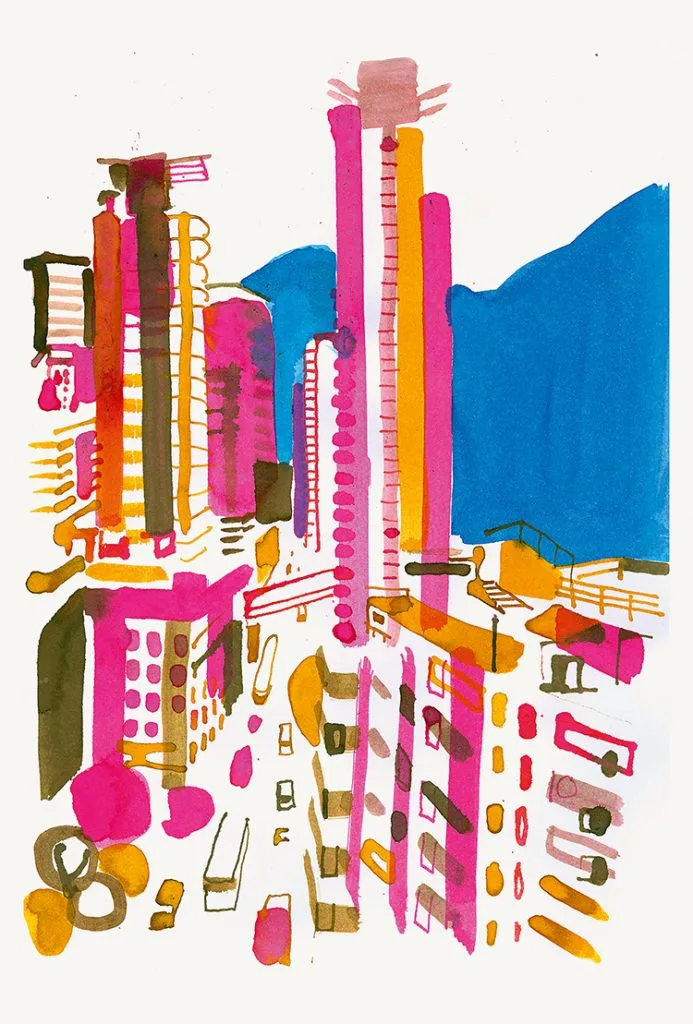

“When I travel, I draw.” That’s how Christoph Niemann begins the epilogue to his brilliant new book Souvenir, a collection of “travel drawings, portraits and still-lifes,” created on his recent globetrotting trips. From South Korea to New York, Singapore to Paris via Portugal, the book captures an amazing array of locations in Christoph’s vibrant style. Whether he is drawing industrial yards or quiet, windswept beach paths, he captures a thrilling sense of place built around spirit and sensibility rather than slavishly detailed reproductions.

The below extract from the book’s epilogue gives Christoph space in his own words to explore his process and what these intimate images mean to him.

*When I travel, I draw.

The first, and most important reason for this: drawing calms me down. I’m very fortunate that my job takes me to places all over the world. I always look forward to my journeys. Usually I’m so focused on the purpose of the trip (often a lecture), that I completely ignore my surroundings.

Even during family vacations, I struggle to let go of my workday restlessness and be receptive for the new environment.

Drawing is the perfect solution: It requires concentration and patience. But since there is

no assignment, there are no expectations and no pressure for artistic success. It’s a pastime, like smoking or drinking coffee, except it’s healthier and lasts longer.

The other reason has to do with my desire to preserve a moment. Whether I’m standing in front of the Eiffel Tower or watching the sunset on a beach, I’m aware that millions of other people have had an almost identical experience. Nonetheless, the moment feels very unique and personal.

The simplest way to capture such a situation is, of course, to take a photo. I always carry my smartphone, and the quality of even a quick snapshot, is becoming more and more impressive.

Yet, these photographs usually fail to capture whatever it is about a scene that moves me. This is especially true when there are no people in the picture. At best, the picture is a visual mnemonic.

Every detail is visible, and even the mood, the light, the contrasts are represented accurately. Once I’m back home and show the photo to somebody, I realize that it fails to convey what’s most important: the emotion. The viewer nods sympathetically but stumped, and I think to myself, ‘Oh, if you’d only been there, you’d understand it’.

A drawing is too abstract to provide an accurate depiction of a place. I leave out far more than I show: objects, textures, people, backgrounds. Elements that are consciously or unconsciously important to me are emphazised, made larger or more colorful than they actually are.

As opposed to my usual work, I don’t go about this analytically. I start with a basic premise – a certain crop, an odd angle, the tension between a person and their surroundings, plants and architecture, technology and nature.

But as soon as the first lines emerge on paper, the drawing decides where it wants to go. This rarely works at the first try. Often it takes multiple attempts. Sometimes, while working on the tenth version, I realize that the second one wasn’t so bad after all and that it radiates an energy all the others lack.

And more often than not, I have to concede, that even after many attempts, there’s no emotional link between the drawing and the scene I’ve attended.

Over time memories change. Most things fade, while others become more significant. Connections arise that one wasn’t aware of originally.

Sometimes a drawing can capture all this in a new and surprising way. And with some luck, the picture feels as authentic as the moment itself.