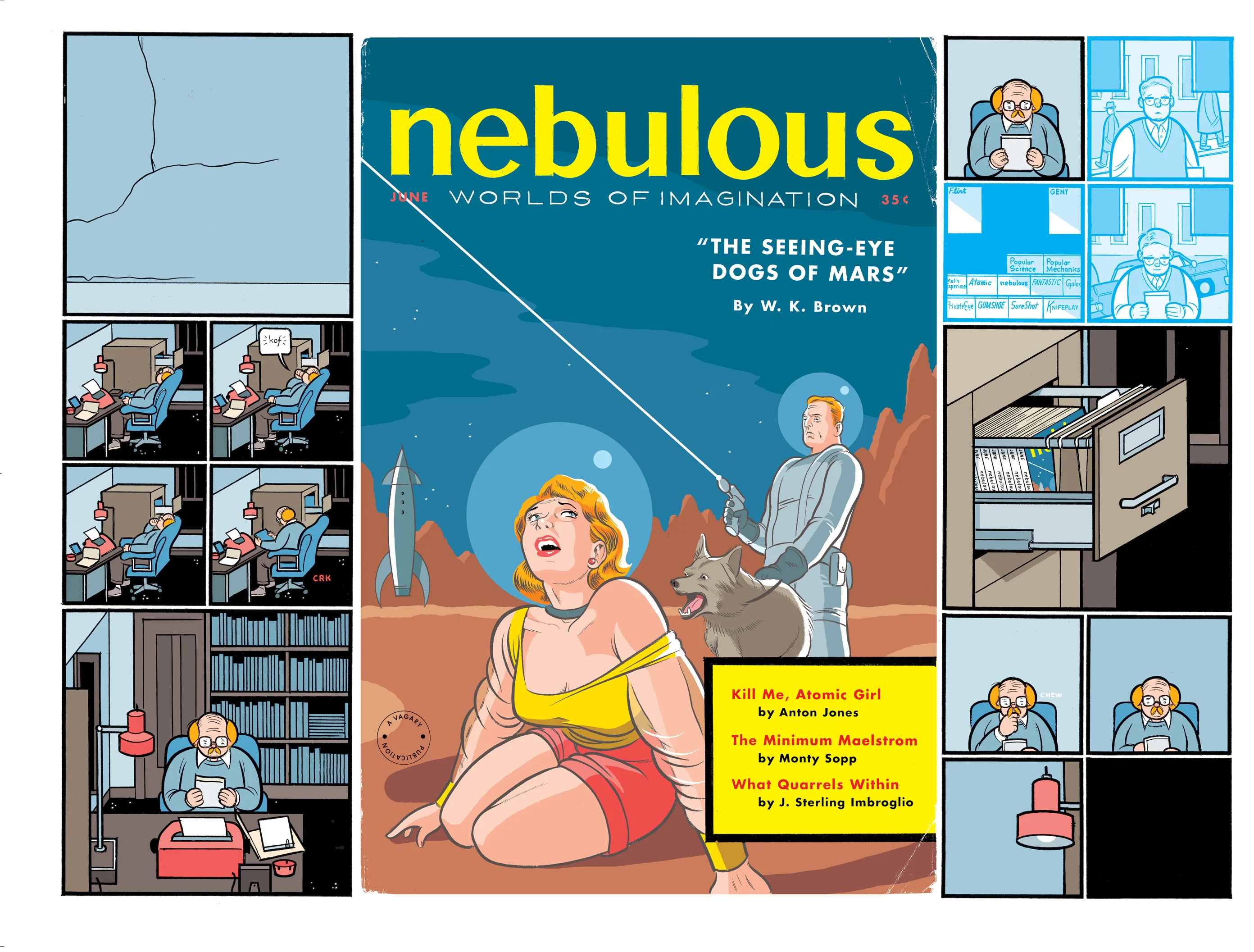

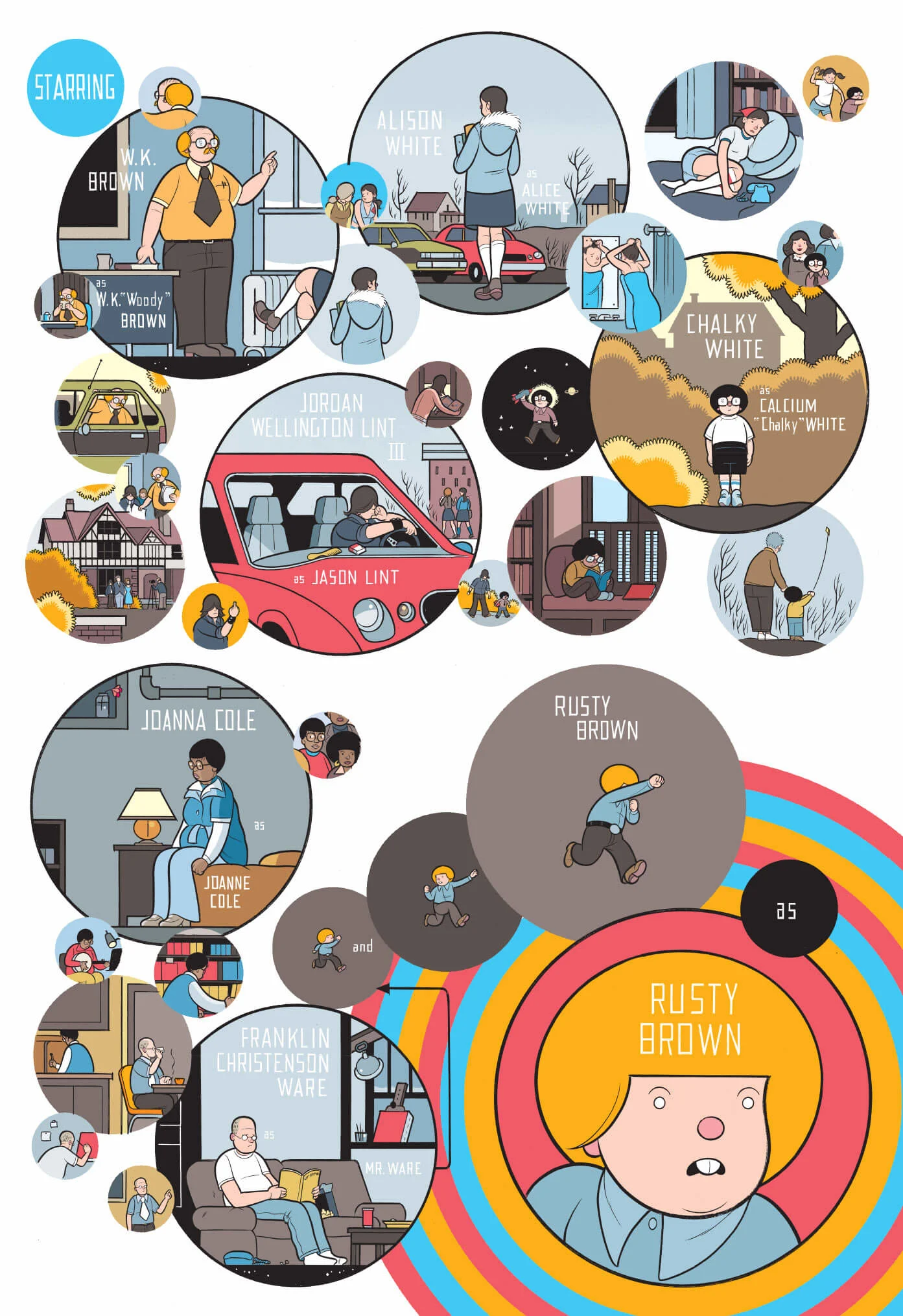

Chicago-based artist Chris Ware is responsible for some of the most critically acclaimed graphic novels of recent memory. The author of Jimmy Corrigan, The Smartest Kid on Earth and Building Stories he has won countless awards and has become synonymous with his ability to turn the banal into the extraordinary. Here we speak to the artist about the release of his latest feat, Rusty Brown.

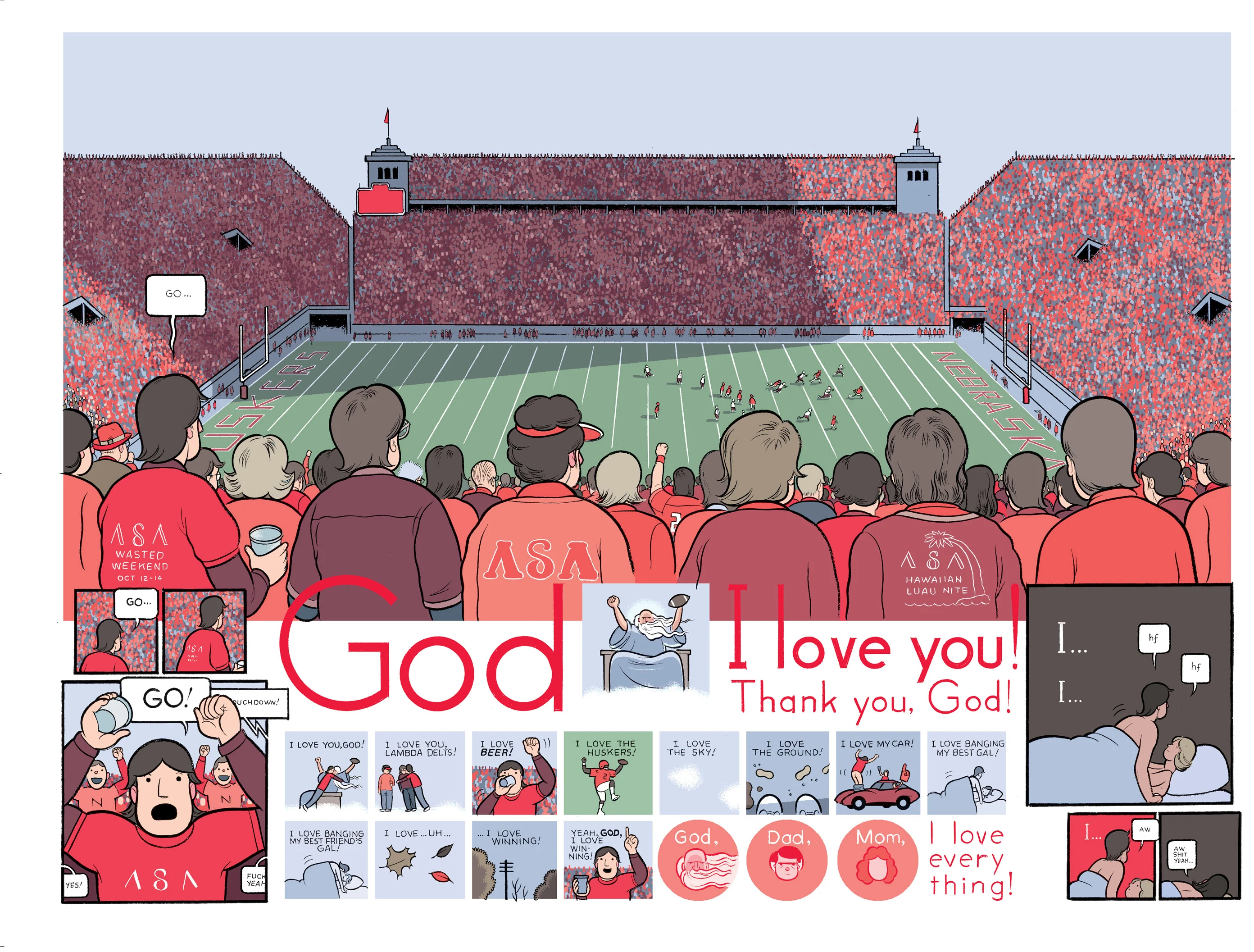

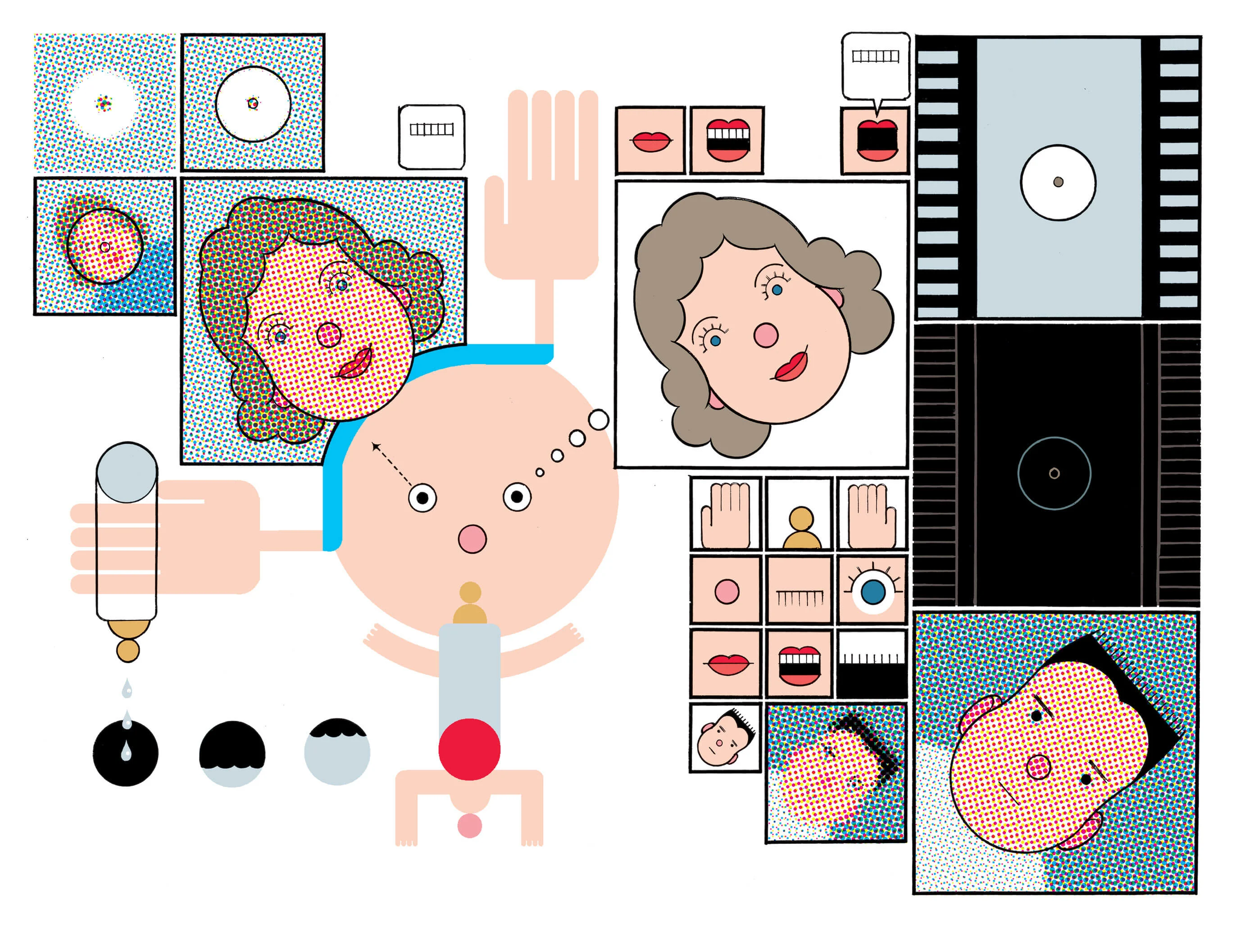

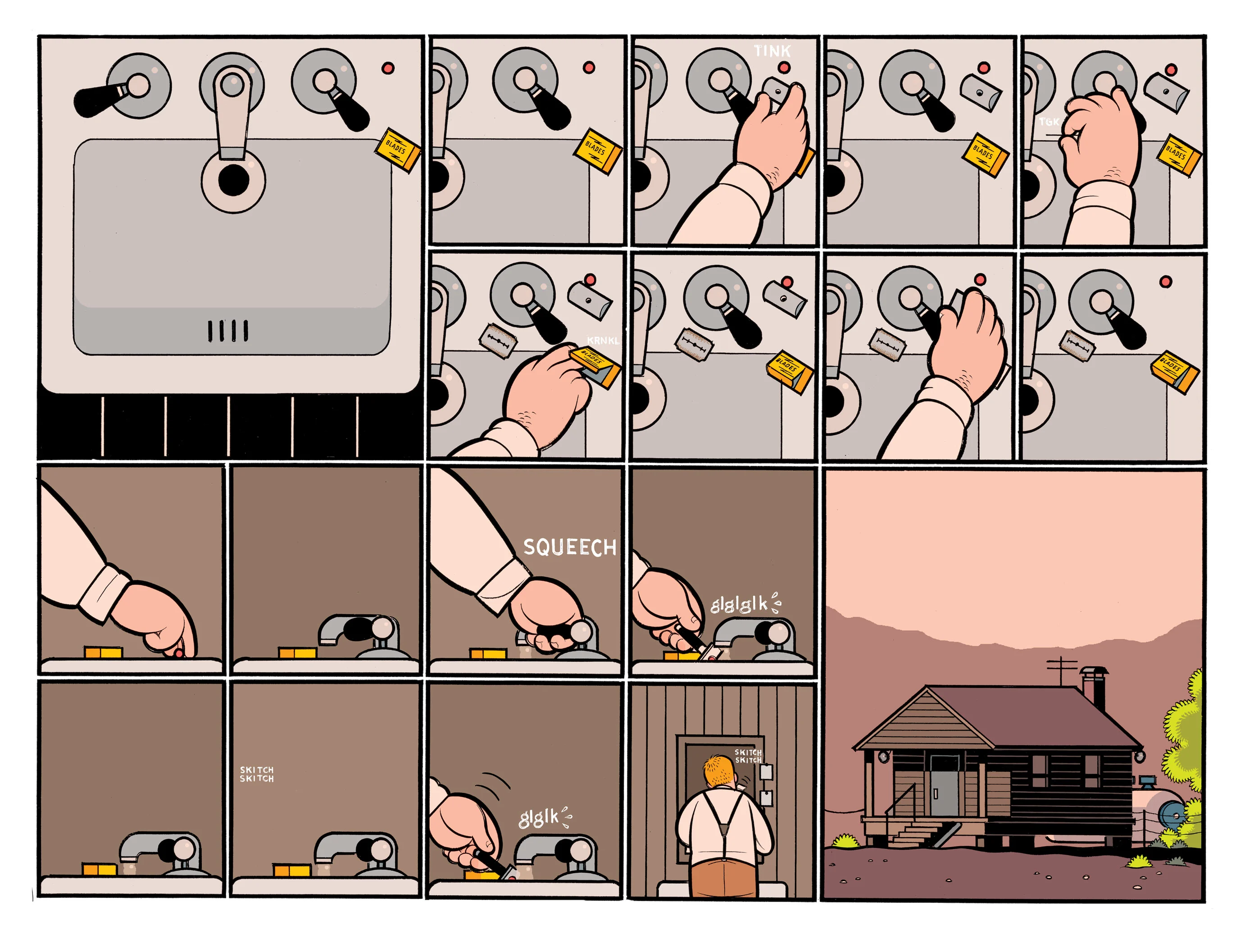

Assiduous, intricate and often spanning long periods of time, the work of artist Chris Ware adds a new meaning to the term ‘labour of love’. Layered with emotional depth and biting social commentary, his work cuts through the zeitgeist like a hot knife through butter. Defying comic book conventions with every project, Chris has never been one to follow rules, and in forging his own path has come up with a style that in unmistakably his own. This inimitable quality to his work has perhaps never been quite so obvious as with his latest work, Rusty Brown - a project that was almost 20 years in the making.

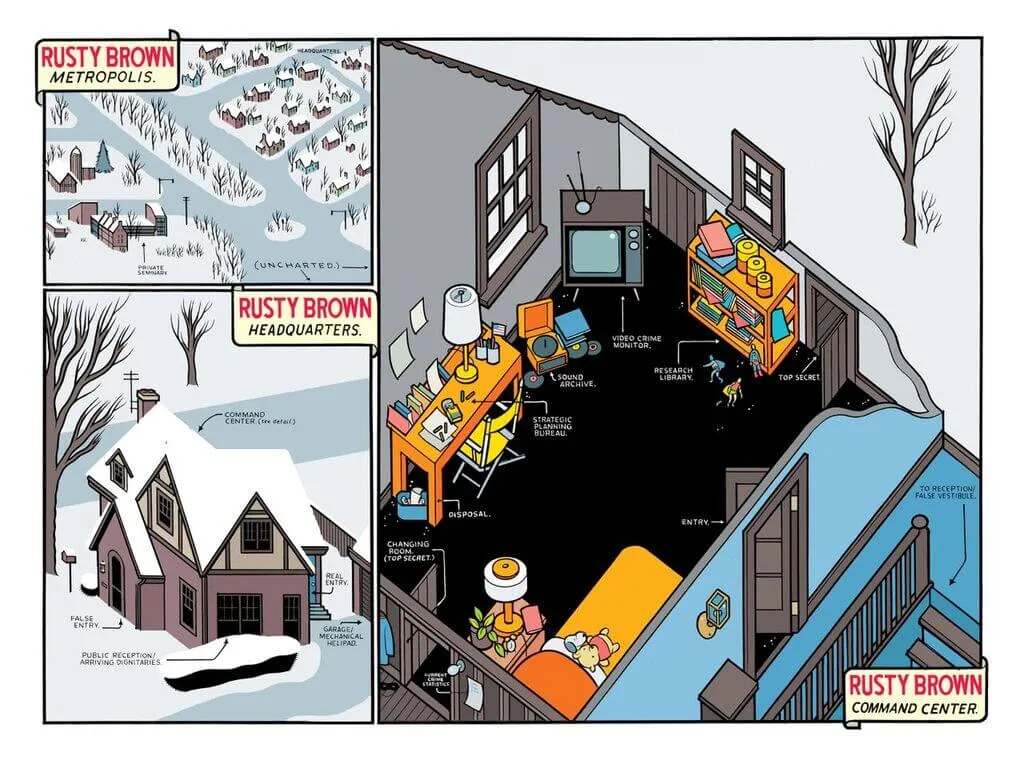

To call Rusty Brown a graphic novel is a bit of an understatement. Clocking in at 352 pages the novel is weighty enough to bench press and spans a huge portion of Chris’ life, starting with his memories of growing up in Nebraska in the 1970s and taking in a fair chunk of everything else that has transpired in the past two decades. It’s a book that has to be seen to be believed and a creative process that deserves some unpacking. We speak to Chris about the project that has turned his life into art, and why comics can capture the ‘slow erosion of consciousness’ better than most.

You started the novel right after Jimmy Corrigan based on 'characters who had originated as parodies' - why were these characters so urgent to you, what was it about them that compelled you to further their narrative?

Because I am a terrible writer, almost all of my stories seem to start this way, i.e. as a satire or gag which then somehow metastasizes into something serious, grave and depressing — sort of like saying "just kidding" to someone when you really mean what you're saying. I’m not sure if this working method is due to my lack of innate confidence or some other psychological problem, but then again it seems to have worked for other authors, like Flaubert‘s Madame Bovary and Melville‘s Moby-Dick, both of which were, I believe, born of satire but ended up at very different finish lines.

When you first began Rusty Brown, did you have any idea how all encompassing the project would become? Was there ever a stage when it became overwhelming?

Actually, I don’t think it can ever become quite overwhelming enough. Sometimes, when I started to think I might have some inkling what it was all “about,“ I'd deliberately thwart that narrative direction and stir things up until I had no idea what I was doing again. I don’t trust books that make too much sense, because life doesn’t make much sense, and life is always the ultimate rubric. At the same time, a story shouldn’t be utter tangles of nonsense, either, and I have a pretty fair idea of where my stories are going, but only about the same I have of where my actual life is going (which is, for example, much different than where I thought it was when I was twelve years old.) Whatever narrative notions I have, however, ultimately take a backseat to the reality of the drawings as they appear, and the images always seem to have a better idea of that than I do. The greatest books have lives of their own; bad books are wrenched and wrestled and bent into shape in the service of an idea. I learned this the hard way, and the results were always disastrous, if not cadaverous — dissected and dessicated.

How has Rusty Brown - the story, the characters - evolved over the almost 20 year time span of the project? And how have you as an artist - your process, beliefs and thoughts on creativity - evolved in tandem with it?

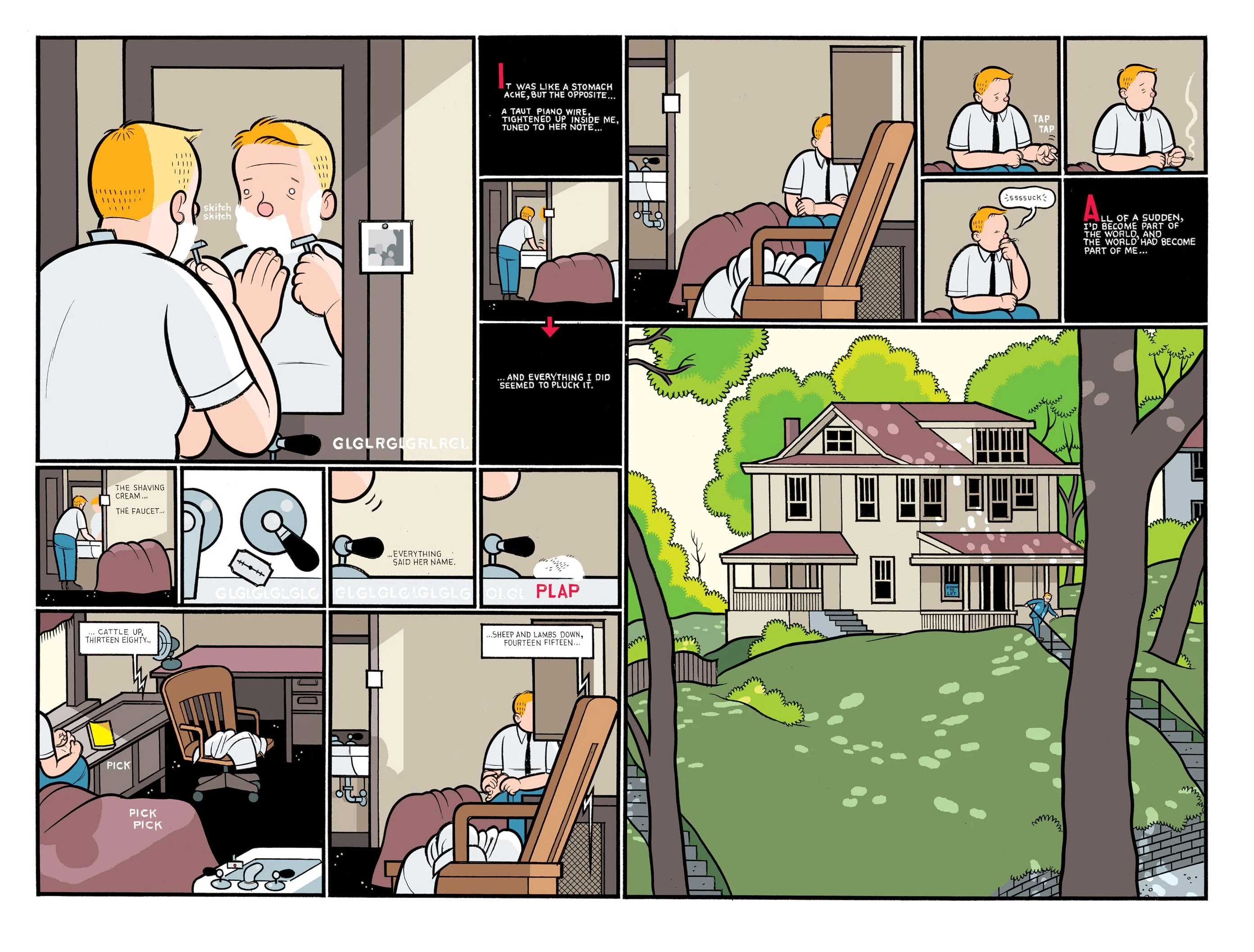

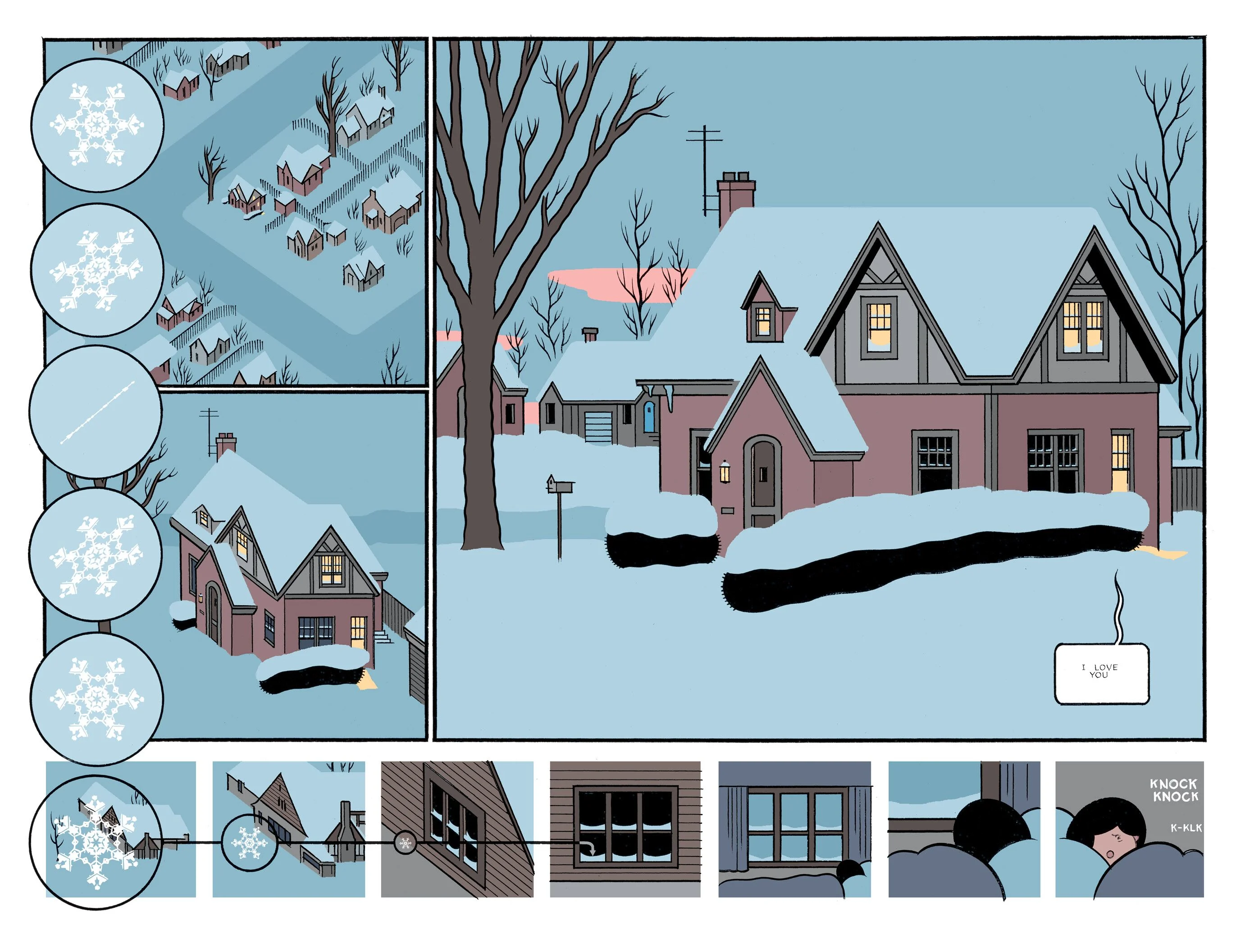

If anything, that’s really the overarching point of the book, to capture this sense of inevitable change and shift of memory as we unseeingly daily and hourly recall and anticipate our lives while life itself passes us by. My memories of my own childhood, details of which I have tried to capture as intensely as possible in the book, have changed in the time of its writing in ways I can’t effectively describe in words but can, somehow, in pictures. There’s something about the medium of comics which captures that slow erosion of consciousness more obviously and affectingly than most, if any, other visual media. Probably the clearest example is how Charlie Brown's face changed over 50 years, from a carefully drafted saucer to a handwritten doodle; somewhere in there is something approximating the calligraphic distillation of Charles Schulz's soul.

I can’t effectively describe in words but can, somehow, in pictures

How did you fit the timeline - a lot has changed in 20 years! - into the novel, how did you choose which elements of society, which elements of change, to include? And what were the biggest challenges?

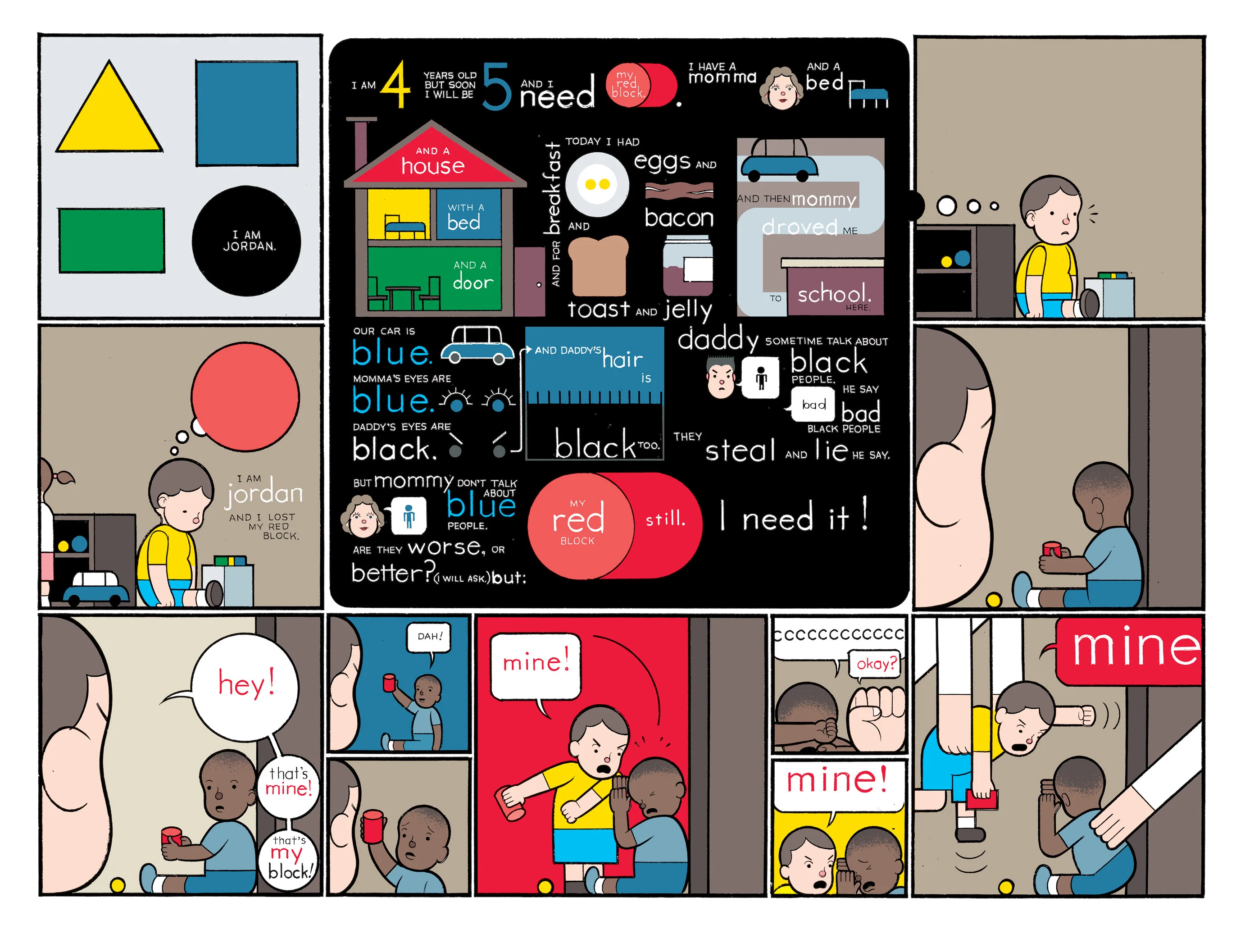

One of the minor challenges of the book was indeed to decide how much of contemporary 1970s political life I would include; at least in the case of the youngest kids in the story, I decided to stick to my own childhood experience, which is basically that my memories of Gerald R. Ford are of him preempting my favorite television shows. However, the 1975 day which is the framing device of the book is only a gameboard from which the individual chapters then veer far from, going backwards and forwards in time sometimes several instances on a page — so there are computers, iPhones and social media along with cruddy economy cars, plaid pants and entrenched racism. This sort of internal time travel is something we all do every day, if not every minute, of our lives, and writers like James Joyce devoted their lives to figuring out how to capture it in words; I am simply trying to do it, however awkwardly, in pictures.

The setting of Rusty Brown is your memories of a childhood in Nebraska. How much of you do you see in this novel? How much of your childhood did you relive, and what effect did that have on you as an artist, revisiting it as an adult? It really feels like a life’s work.

Sadly, it is a life’s work, and even more sadly, it is all me, even the characters who seem demographically furthest from a 51-year-old middle-aged middle-class white male who spends most of his time at a table kvetching about people who wronged him four decades ago. More importantly, though, the book is very much about trying to understand and inhabit people who are not me, since really that is the most important task that we as humans can do. When I was in art school, I was told that by drawing women I was “colonizing“ them; aside from how strange and wrong it would be to write and draw a book without any women in it, I know I was then, and am now, simply trying to empathize with others. If that effort is somehow wrong, then I take full responsibility.

Further, if one cannot — or even worse, should not — try to understand and empathize with those wronged, subverted or stolen from, then I don’t know how else to try to better the world. We have to try to get past the example of the current American president, whose thieving and lying mode of “success“ is so much simpler, easier and effortless than someone who tries to remain truthful, open and sympathetic. I hope that once Trump's tenure is over he will have served as the last gasp of this penis-centric mode of conquest which has characterized not only my country for almost 400 years, but for millennia.

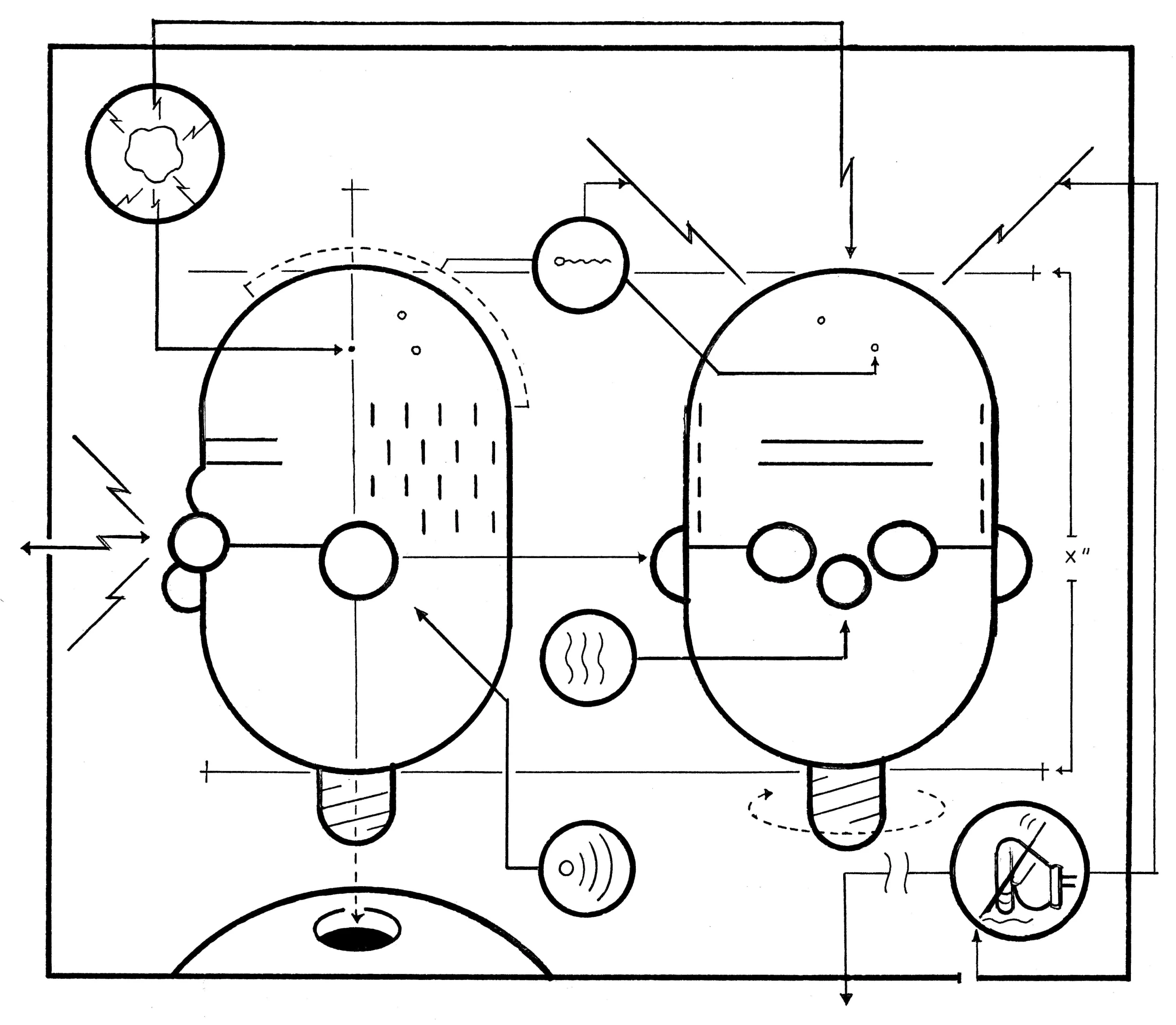

Can you talk us a bit through the process of creating and how that itself changed over the duration of the novel?

It’s pretty simple: I sit down and I draw. More often than not, though, I get up and wander around and do anything I can to avoid sitting down and drawing. But once I do, again, the drawings tell me what to do, and I try to listen to them, in the same way that a writer tries to get caught up in the flow of his or her words on a page. Drawing comics is a little less like carpentry and a little more like gardening; it takes patience and a lot of time and self-doubt and trust. I spend about a week drawing two pages, after which I enjoy a brief (+/- 15 minutes) of relief before the anxiety sets in knowing I have to start all over again.

Drawing comics is a little less like carpentry and a little more like gardening; it takes patience and a lot of time and self-doubt and trust

How does it feel finally releasing this labour of love to an audience and is that ever difficult as an artist, allowing outside perspective on your personal characters, particularly in a project as intimate as this?

It’s made me horribly anxious, fretful and paranoid that I have wrought 352 pages of full-color self-indulgence and pointlessness. At the same time, I know it represents the very best that I could possibly manage at the moments at which I drew every page, and that it also represents my attempts to always try to see the good in those “people“ I have imagined, even if that good is not immediately apparent. Again, I think there are few skills more worth honing than trying to see the good in others.

In our current society where ‘content’ has become disposable and people are encouraged to work quickly, how important is it for creatives to be able to really take their time with work. How much value do you see in that?

I think it’s extraordinarily important. I hate Facebook, I hate Twitter and I especially hate the people who run those companies with their cultivated guru-like posturing, claiming they are bringing us all together when they are really providing hyper-amplified and artificially-flavored ways of driving us apart, to say nothing of stealing the inner self as quantifiable and saleable data. Trump understands this better than anyone, and he's playing America like a toy xylophone, using the internet to divide and conquer, the oldest trick in the book. This court of instant verdict asphyxiates the possibility of nuance and humane consideration. I can’t believe that we all really want to live in a world of faster-than-light algorithms of judgment, and I'd love to imagine that humanity will reject it all, but I know my wish is stupid and naïve, so as in all things catastrophically "innovative" we'll have to adapt and, most importantly, mature from within to master it, or it will master us.

Do you feel like there is more to explore with Rusty Brown, or is this chapter now closed?

It's only halfway done, and I suppose I'll be working on the second half for the better part of the next decade, but it’s not as if the world will stop turning waiting for it. All I can really hope for is that the book will improve as I age and I'll develop an ever-finer and more careful scrutiny of life, to say nothing of an ever-expanding view of humanity and possibility for this still-young medium. At least that’s my aim.

As a creative how long do you sit with a project before moving onto the next. It was immediate in the case of Rusty Brown, but will that be the case moving forward?

I’m working on two other graphic novels concurrently, just as I did with Building Stories, and whereas Building Stories was an attempt to write a book with no beginning or end, Rusty Brown is an attempt to write one with no protagonist, despite the very misleading and embarrassing title with which it is slapped. At least I am not alone in this regard; Moby-Dick's main character certainly isn't a whale, and nearly every single one of Herman Melville’s books (i.e. Typee, Oomo, Billy Budd and of course Moby-Dick) are also all deeply embarrassing to say out loud. Maybe he was on to something.