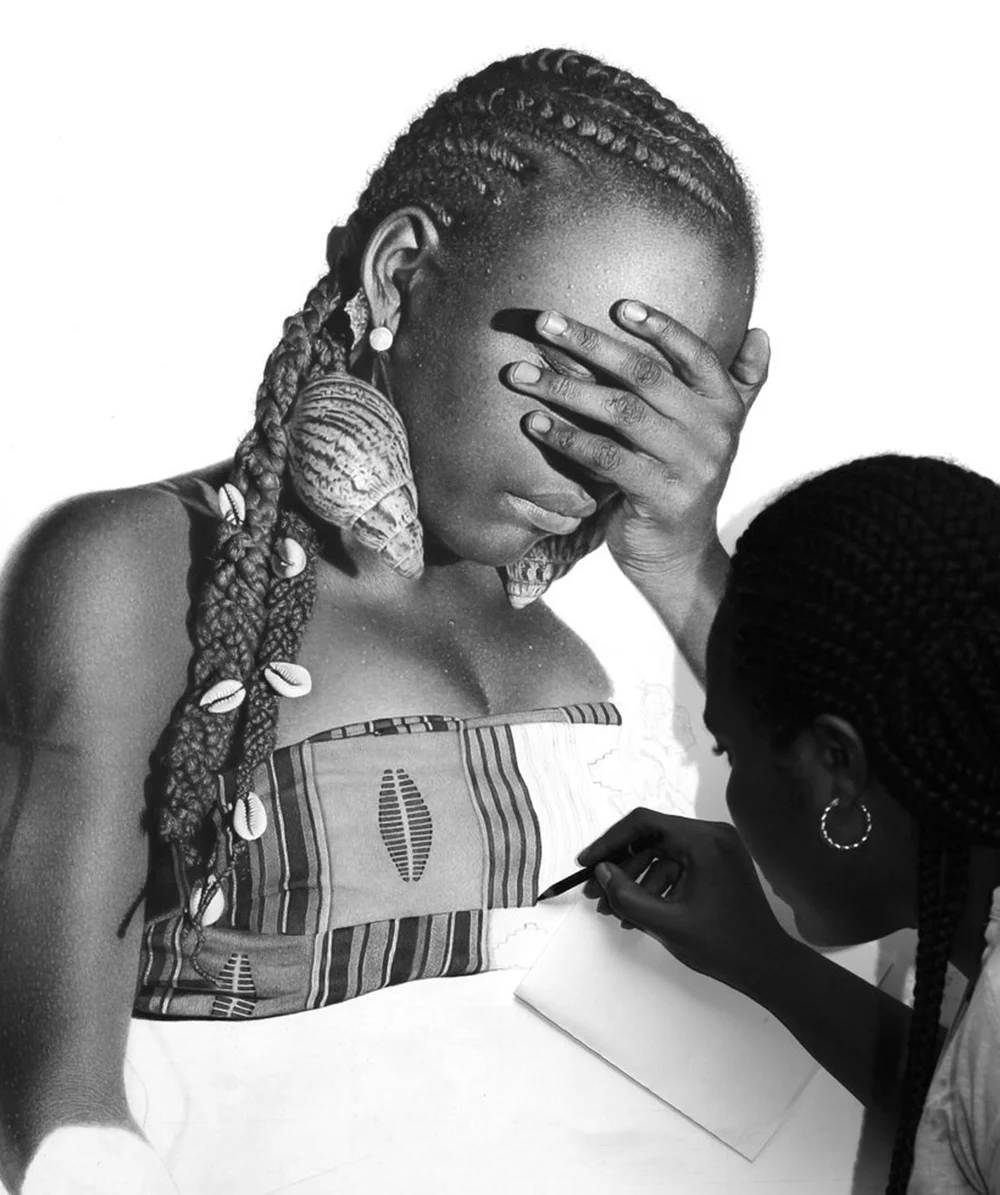

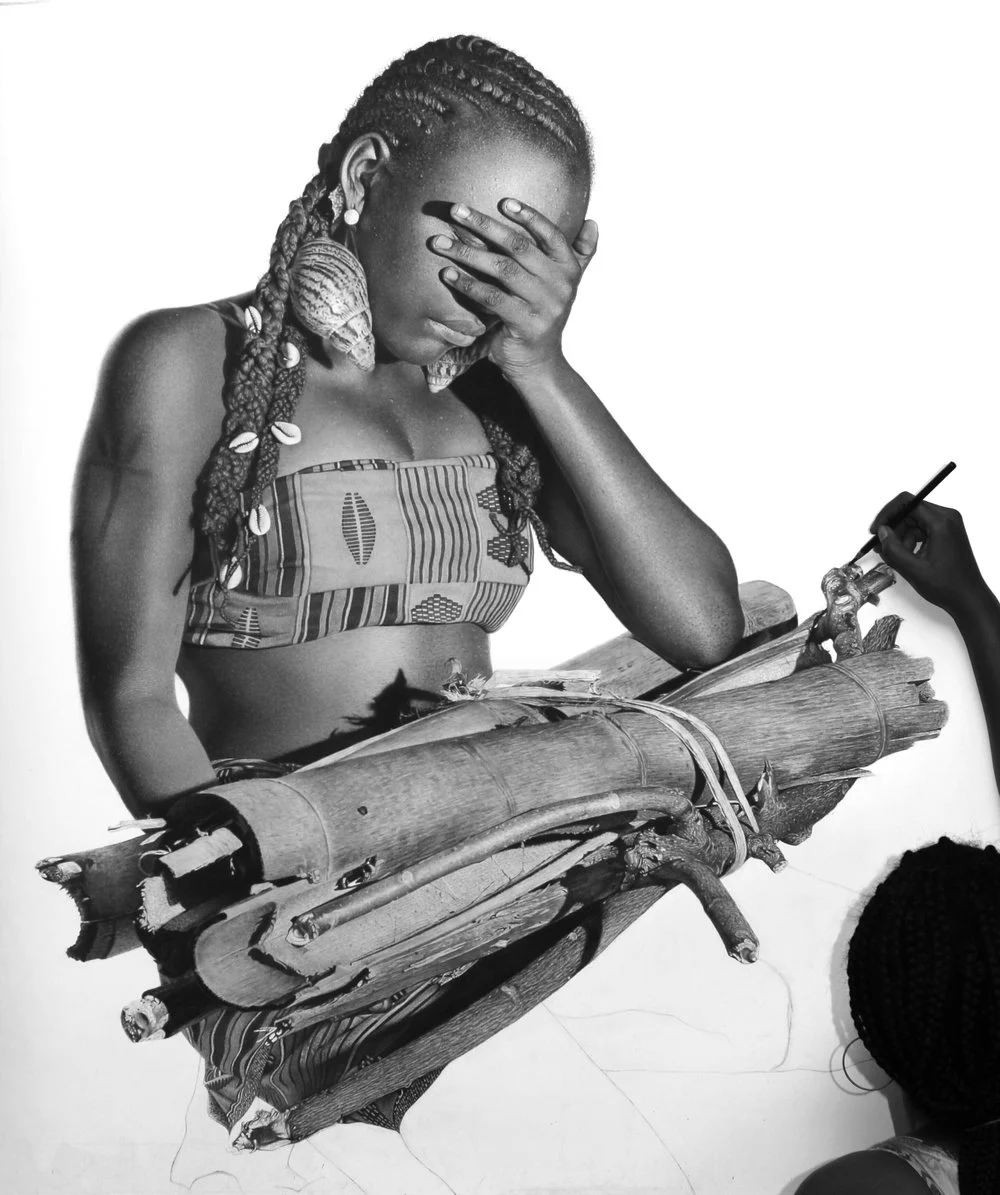

Chiamonwu Joy’s astonishing artworks could easily be mistaken for photographs. It’s only when you see her works in progress – the paper-white outline of an unfinished arm, or the Nigerian artist’s hand adding a finishing touch – that you realise the optical illusion.

While a picture takes a fraction of a second to appear in digital form, a drawing can take Chiamonwu from three weeks to two months to complete, depending on its size and subject. Daily realities dissolve when she picks up her pencils to draw. “It's like time doesn't matter,” she says.

Chiamonwu first discovered hyperrealism on Instagram and immediately fell for the style. She practised drawing this way by following online tutorials and it’s taken her four years to get to this level, but she’s determined to improve even further.

There’s one downside to drawing hyper realistically though; training your eye to notice such meticulous detail means you also see the minute mistakes that others wouldn’t. It’s become a habitual part of her process to scan her works for areas that could been improved upon. “I’m the first and biggest critic of my artworks,” she says.

The people in Chiamonwu’s pieces are mostly family members and a few friends who she considers her muses. She styles, stages and then photographs them to create the reference material from which she draws. “I decide who and what to draw next depending on how physically, emotionally, spiritually and psychologically attracted I am to the subject or object,” she says.

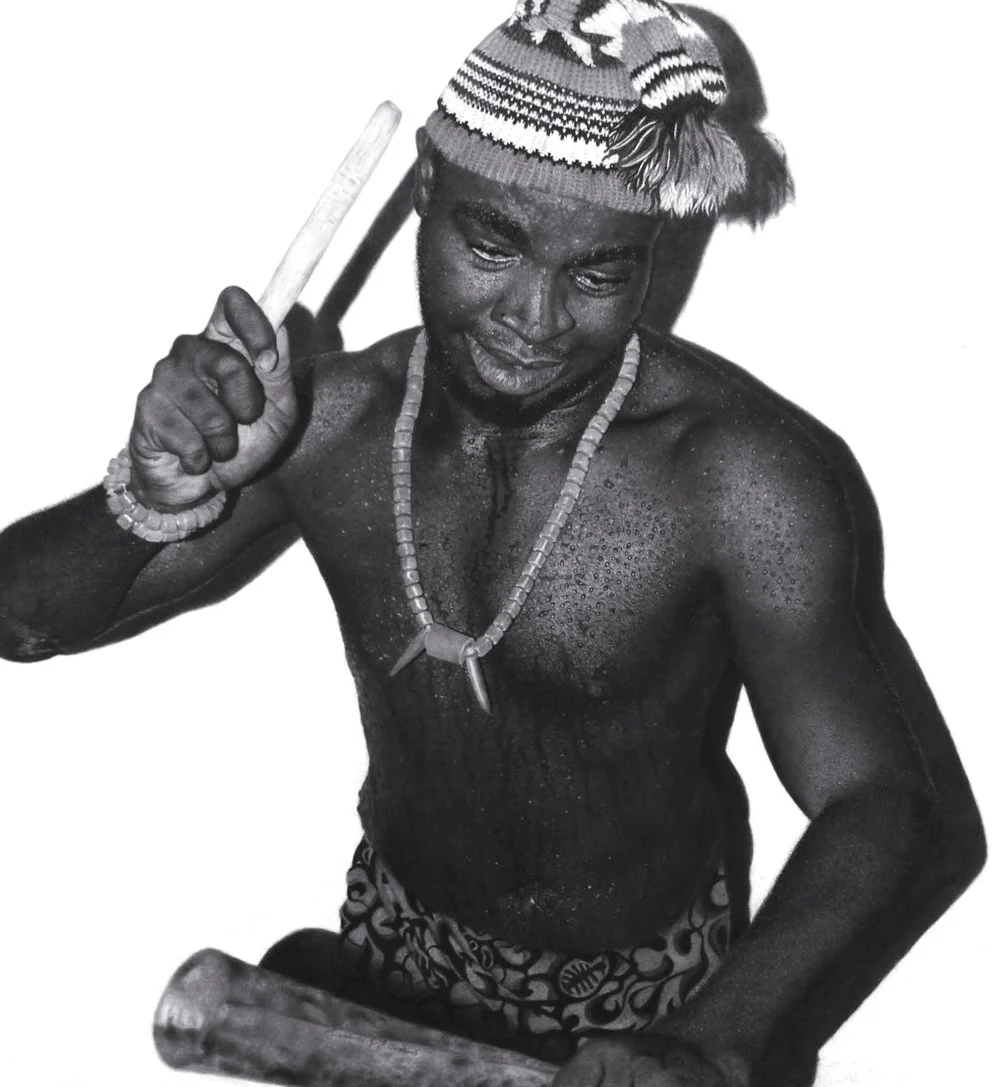

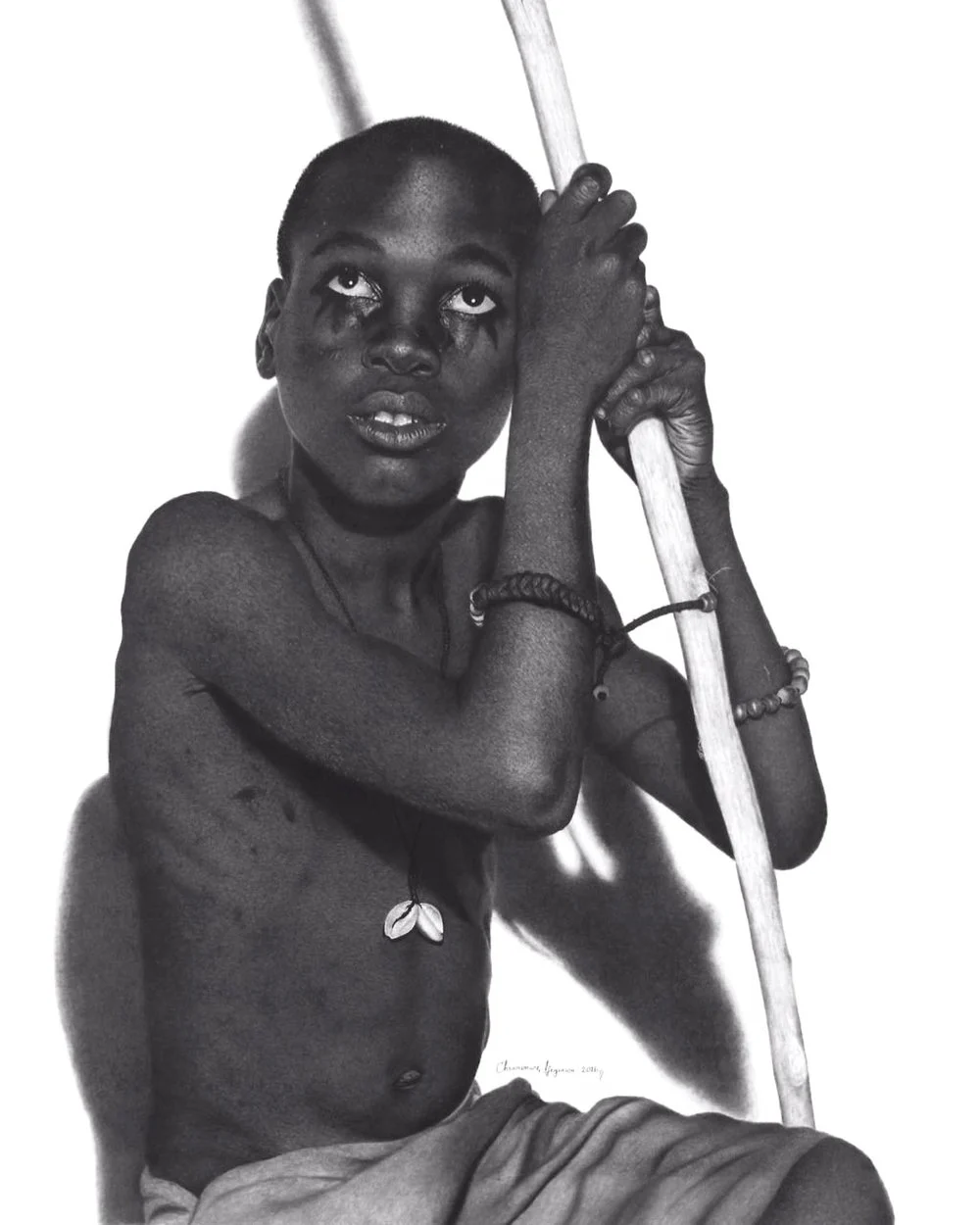

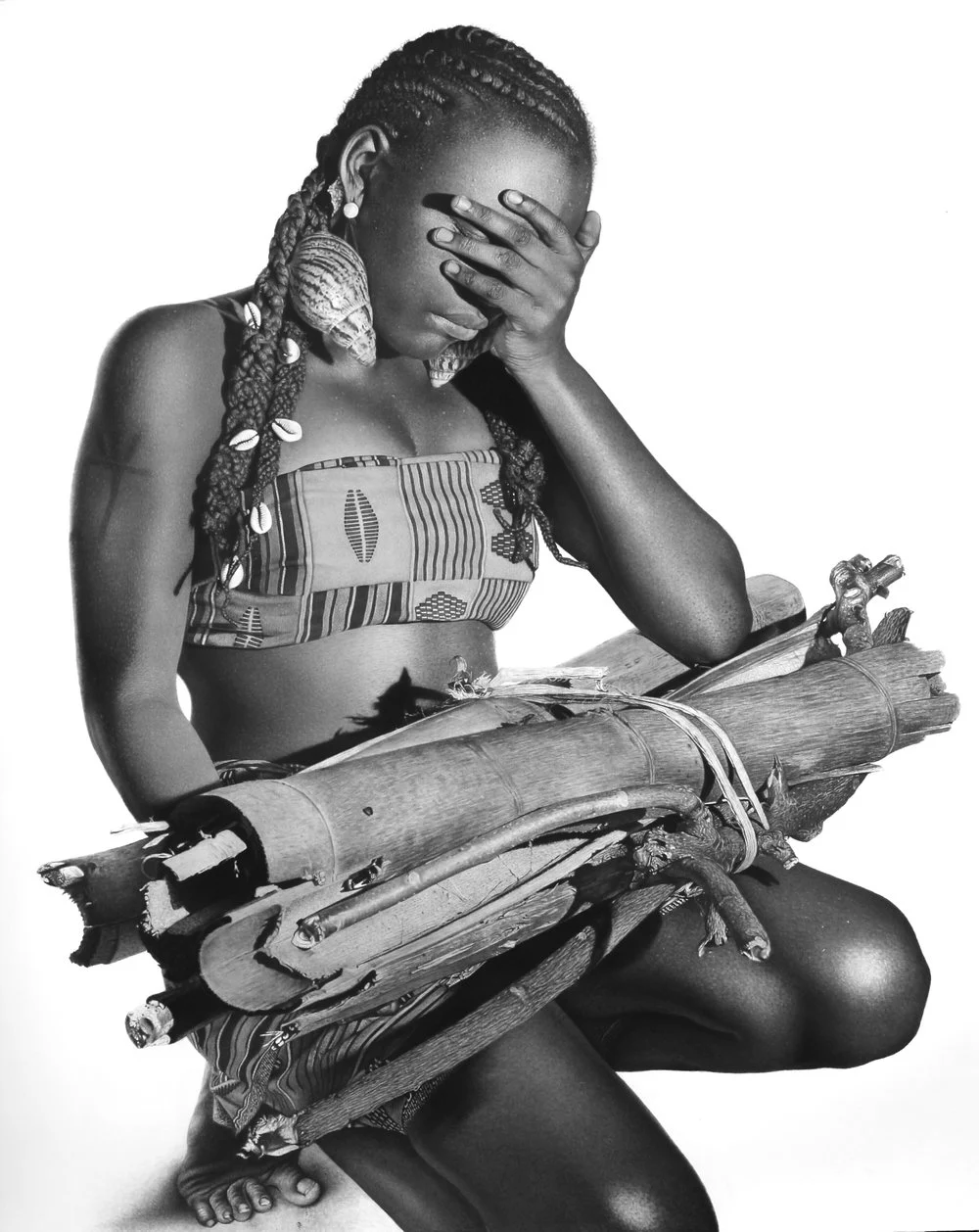

Using graphite or charcoal, Chiamonwu begins at the top of the page working her way down – incrementally adding light and shade to replicate the luminous skin you get when using a flash camera. Every hair and fibre is eventually revealed in crisp detail.

I learnt to be more patient, to be cautious but also to take risks for what I believe in.

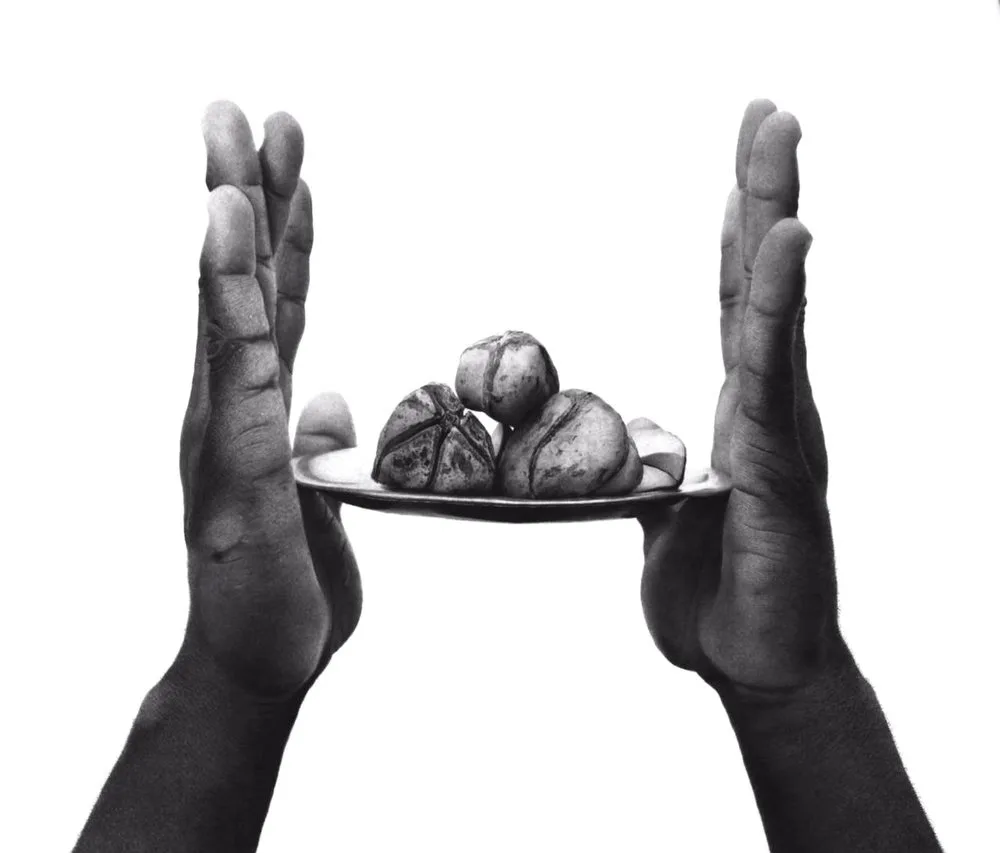

Chiamonwu was born and grew up in Maiduguri in the northern part of Nigeria and now lives in Awka in the south east of the country. Her incredible skill aside, at its heart, her work is about documentation and preservation of her Igbo culture. Her drawings feature a woman wearing cowrie shells woven into her braids; two hands hold up an offering of kola nuts; a boy wears painted markings under his eyes.

“Everything they’re wearing is a symbol of my culture,” she says. “The attire, the hair-do’s, the accessories and all. They all represent the Igbo culture and traditions and what we value.” Some of the rituals she recreates are dying practices. “I have read lots of historical books about my culture,” Chiamonwu says.

“My art tells a story of typical Igbo culture before westernization and globalization.” It’s become her mission to immortalize these customs that will surpass even her own lifetime.

As much as her work is art, the painstaking practice is also discipline. “What I like about this genre is the patience and dedication that comes with the skill,” she says. Her training has revealed qualities in herself she didn’t know she possessed.

“I learnt to be more patient, to be cautious but also to take risks for what I believe in. It has shown me how limitless we humans can be when it comes to nurturing or harnessing our passions and our skills.”

Words by Alix-Rose Cowie