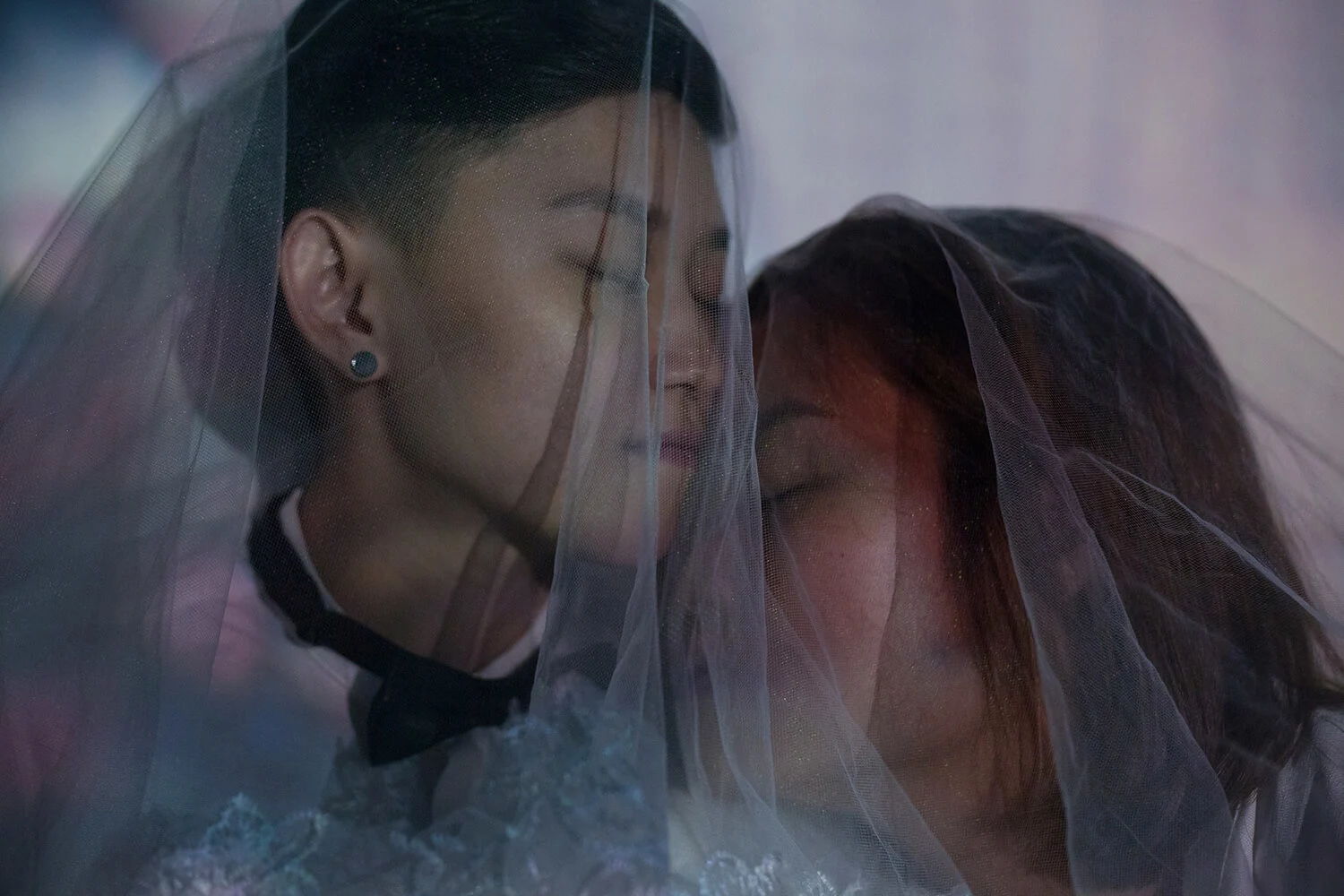

In subdued lighting, a couple rest their heads together in a loving embrace beneath a white veil. Projected onto the wall behind them is an old wedding photograph, the bride in a big white dress and the groom in a black suit with a bow tie. The photo is from the ongoing series by Singaporean-Chinese documentary photographer Charmaine Poh called How She Loves.

This story is part of our Through The Prism of Pride series, where we present stories from LGBTQ+ communities around the world. From London to Lagos, we explore how creative expression can bring about change, understanding and acceptance. See the whole series here.

The series is about queer women living in Singapore, but the staged wedding celebration is a life-event the couples won’t have access to in real-life since same-sex marriage is unrecognized in the country. While Charmaine has noticed that society in the island city-state has gradually become more accepting of LGBTQ+ people over the last decade, the laws remain unchanged.

“Infrastructurally speaking, the government's policies towards homosexuality remain pretty much unyielding,” she says. “They are pragmatic in understanding that queer people exist and are valuable resources to society, and therefore they tolerate a quiet existence, but resist any obvious acceptance or celebration of (the LGBTQ+ community). The law continues to criminalize sexual acts between men, and women aren't mentioned, but this penal code is not actively enforced. It's an apt parallel to the tension that the community lives in.”

Much of Charmaine’s work draws from portraiture. But for this project she wanted to see if there was a new way of investigating what queer love looks like. “I wanted to see what love and attraction looked like between two women and if it could be captured in a photograph,” she says. In her studio female couples step into a make-believe world where they have permission to marry to each other.

Charmaine dresses the set with signifiers of traditional white weddings: cloth, wine glasses for toasting, pink bouquets and flowers petals. The couples are invited to accessorize with bow ties and veils, or not. In the subtly lit room they can play out wedding tropes and traditional gender roles for Charmaine’s lens, or decide to go down a completely different route.

“I just wanted to create an imagined world and see what they'd do with it,” she says. “Would they adopt gestures from conventional romantic imagery? Would they subvert heteronormative roles? I didn't know, and I wanted them to show me. The way we act in this given situation says a lot about how we see ourselves.”

The people in the projections are their own parents on their wedding days. “I wanted the couples to feel the bearing of their parents' history on their bodies,” Charmaine says. “It's not only heteronormative, but also so deeply personal, because family often remains a topic of heartache and tension among the queer community. And I wanted to visualize what it meant for them to have a partnership so different from the one that brought them into this world.”

Making How She Loves is the first time that Charmaine has invited her subjects into her space instead of bearing witness to theirs. “It turned out to be for the best,” she says. “I wanted them to feel free, and sometimes being at home with family limits that. I wanted them to breathe.”

Making documentary images, it’s important that her subjects feel comfortable enough to act in an authentic way; to share their truth. It’s also vital that she captures a moment that speaks to her as the photographer. A large part of Charmaine’s process is getting to know her subjects before any shutter clicks. “I think an important part of making work like this, at least for me, is a sustained hanging out,” she says.

She begins by conducting an informal interview to get a sense of what the couple are like with each other and what makes their relationship unique. This gives her clues as to how to document them. “I’m therefore able to make portraits that speak to their reality, while at the same time they've warmed up and now trust me to create the images I have in mind.”

Charmaine works instinctively so while she’s making the images, she’s guided by what speaks strongly to her. But, she’s also aware of the eyes of an audience. A question she asked herself constantly, was: “Could I bring the viewer into their world and cause them to feel what I and the participants felt in that moment?”

She hopes to inspire empathy and to start a process of normalizing queer partnerships in the minds of her viewers. “I am cognisant of the importance of making this project for a public audience made up of both people who identify with these images and those who view them with curiosity, unfamiliarity or perhaps even revulsion,” she says.

“I think we as image-makers have the power – in our own little corners of the world – to shift visual culture. And I want to play a part in shifting this culture towards that of an acceptance and celebration of identities.”

Words by Alix-Rose Cowie.