Leonardo da Vinci once said that, “art is never finished only abandoned.” He was talking about the inherently infinite nature of the creative act, but his words have taken on new meaning in our modern culture, where questions of artistic ownership and copyright have complicated this idea of when an artwork is complete.

The music industry has wrestled with these questions for several years – how does a creative culture based on remixing and sampling coexist with laws about who owns what? This topic was explored in Copyright Criminals, a 2011 documentary (with a surprisingly sparky introduction from Hollywood star Maggie Gyllenhaal). It’s a strange film that flits between hip-hop producers, attorneys and intellectuals, but it does a good job of delving into this clash between art and ownership.

There’s a moment in the film where one interviewee becomes particularly impassioned. “Look at how Shakespeare made culture, look how Homer made culture,” he says. “It’s about collage, it’s about taking bits and pieces of your influences and forging them into something newer and stronger.”

He’s not the only person in the documentary to bring up art and collage as a frame of reference. But it’s an issue the art world has struggled with too. Shepard Fairey settled out of court with The Associated Press who sued him over the famous Obama hope portrait (which was based on one of their pictures of the future president). Writing in The New Yorker, Ben Mauk told the story of the clash between photographer Patrick Cariou and artist Richard Prince, after the latter modified Cariou’s photographs of Rastafarians and presented them as new pieces of art.

As Mauk writes: “At stake is the question of how artists are to produce relevant work about a society that is more saturated than ever with ready-made images, many of which are under copyright.”

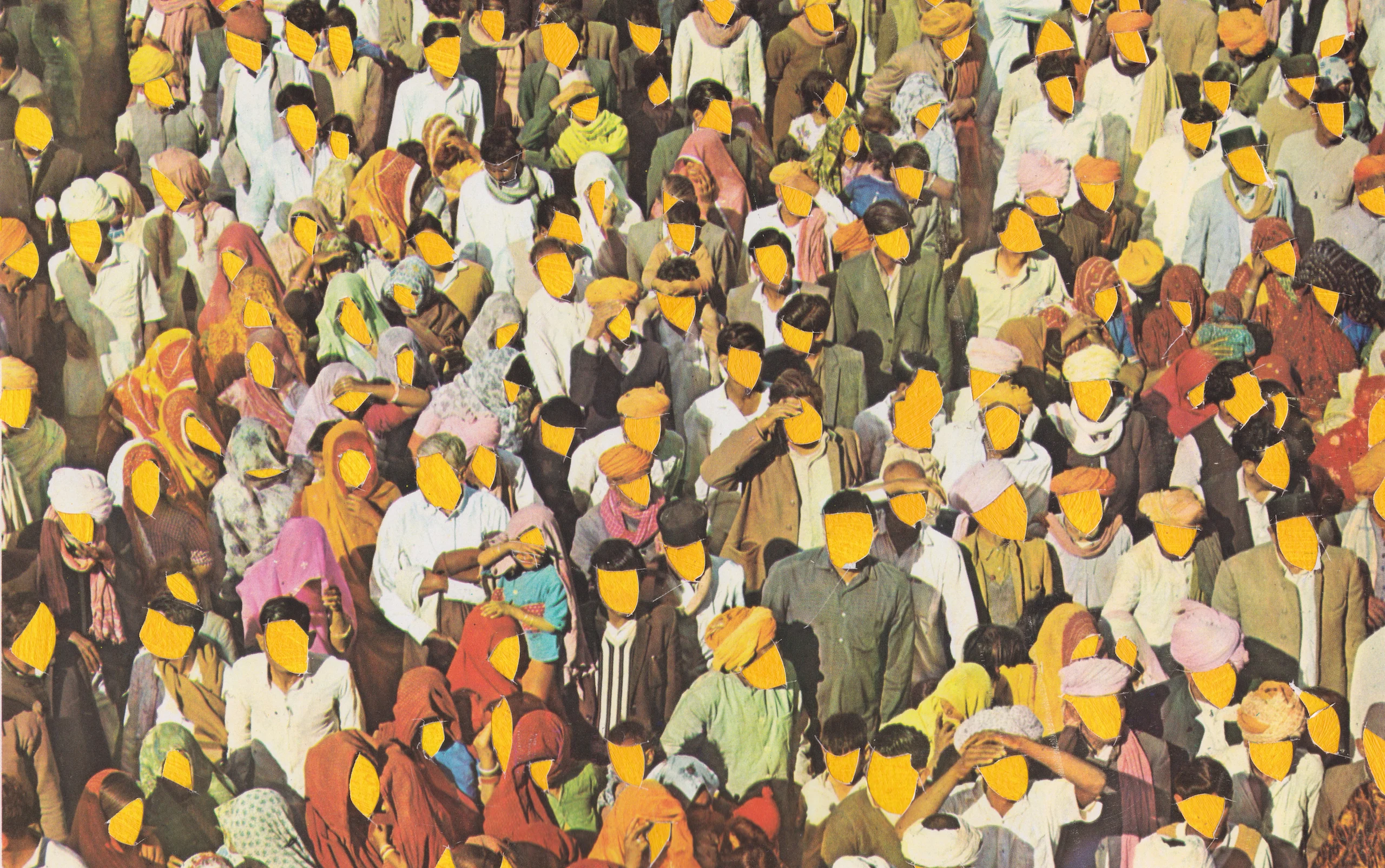

Into this debate steps Dutch artist B.D. Graft and his deceptively simple project Add Yellow. One night in his room, Brian was flicking through a nature book when he impulsively grabbed a nearby scrap of yellow paper and placed it over a picture of a parrot. He liked how it looked, but it also got him thinking about the artistic act. Did altering this image – even so bluntly – make it a new piece of art? Or as he puts it on his website – “Is it mine if I add some yellow?”

An idea was born which became a collaborative Instagram project, and as it has evolved so have Brian’s interests in this area.

“Collage artists are often confronted with questions of copyright and ownership,” he says. “Can I take and use this image? Will I get sued? If I use it, when will cease to be someone else’s and become my own? Does such a line even exist?”

“This project deals directly with these questions, employing a common theme – the colour yellow – to alter, and thereby attempt to claim, art. But making the alteration of the original image minimal (by making a simple addition, as opposed to cutting up and re-arranging certain elements), the collage becomes arguably more self-reflexive and conceptual than traditional ones.”

Brian explains that selecting the original images comes down to aesthetic preference (he believes black and white photos work particularly well) and although the choice of yellow was coincidental, he believes it carries less connotations than a colour like red or black.

For Brian, artists will only be inhibited by copyright concerns if they let themselves be. He explains this in terms that very much mirror the music industry.

“That’s one of collage’s main allures: to take, sample, and remix the existing, most of which was originally someone else’s, and make it your own. Often, as is the case for the Add Yellow, it’s the opposite of inhibiting: it offers a great means of expression and an interesting dialogue.”

And although reactions to his project have been mainly positive, he says that some people haven’t been fans. “They don’t really understand the concept or fail to see its significance,” he says. “But that’s cool – all interesting forms of art have their haters.”