Before the internet, family photo albums brought out on special occasions would hold the memories of Britain's Black communities. Now Jesse Bernard investigates how archivists and photographers such as Rudeboys & Rollups, Black In The Day, Adama Jalloh and Bernice Mulenga are bringing the past into the present and ensuring it provides a reference point for the future.

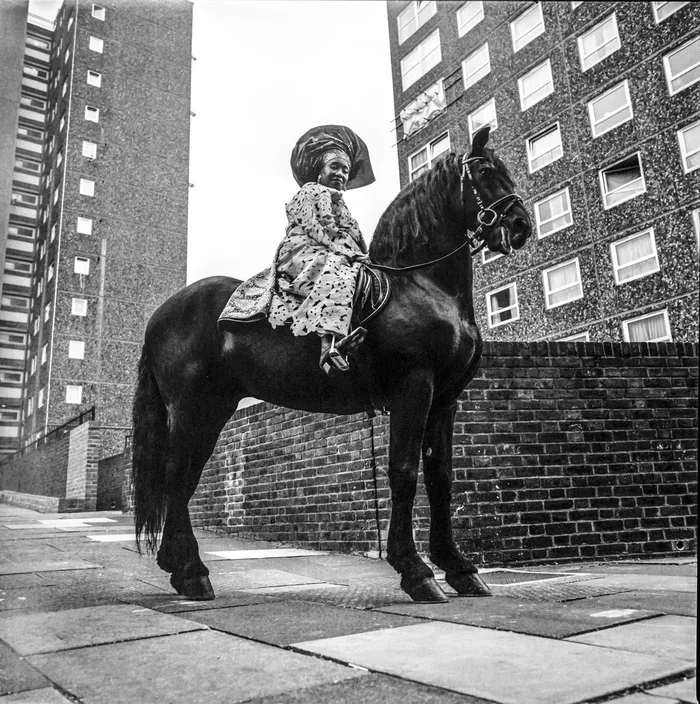

There’s an age old proverb, ‘it takes a village to raise a child,’ but as the child grows and goes through various stages in life, the collective memory of the village often survives through physical memory. “There’s a consistency with immigrants standing firm in maintaining their identity, whether that’s through traditional clothing, our mother tongues or regular gatherings,” Peckham-based photographer Adama Jalloh says. For decades, Black British artists in communities across the United Kingdom have sought to immortalise the memories of the neighbourhoods that taught them to walk the streets. Photographers - Neil Kenlock in the 1970s who captured many of the Black liberation activists including the British Black Panthers and Liz Johnson Arthur’s work decades later in the 1990s - aimed to capture the essence of the various degrees of Blackness in Britain that reflected the rich, vivid and colorful life of dynamic communities that the mainstream media often doesn’t portray.

It’s beautiful seeing how there’s still forms of repetition with how we do certain things.

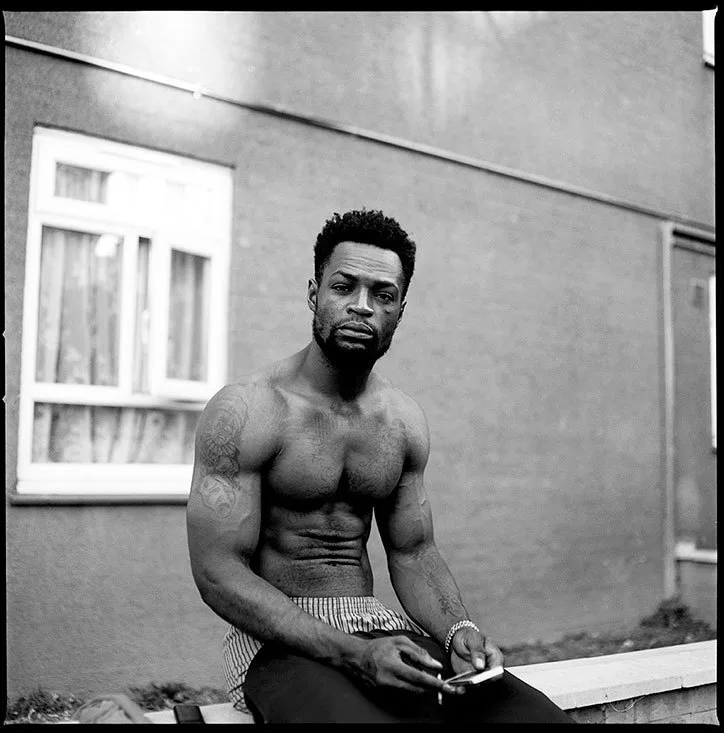

Raisied in Peckham in South East London, photographer Adama Jalloh is an artist who in recent years has taken up the mantle her predecessors passed on to capture Blackness in Britain in its full complexities. Her work predominantly centres on people from her community but in the past couple of years, since graduating from the University of Bournemouth in Commercial Photography, it’s led her to shoot artists such as Little Simz, Octavian, Swindle, D Double E and many more. However, the strength of Adama’s work lies in the fact that her shots often look as though they could’ve been taken anywhere between thirty, twenty or five years ago.

“A lot of our parents immigrated to London at a really young age and, even based just off memory and family photos, there have always been common threads that I noticed that are still apparent now,” she says. “These cultural values are retained and passed down from each generation. Obviously things aren’t completely the same as changes are bound to happen, but I think it’s beautiful seeing how there’s still forms of repetition with how we do certain things. I think it contributes to why at times it could feel like I captured a moment in any era.”

This repetition of how certain cultural rituals are carried out is vital to ensuring younger generations are able to retain a sense of identity, particularly in London where there has been increasing displacement and upheaval due to the effects of gentrification. In the five years since Adama graduated, she’s also noticed a significant difference in her own work as she looks back on it. “It was becoming more and more apparent that a lot of recognisable places within black communities were now replaced with buildings and shops that at times feel very out of touch,” she says. “So for me there’s a sense of relief that I've happened to capture Black people and cultural establishments in those areas that aren’t just a distant memory and it’s possible for people to photographically look back at, so that those communities still feel vivid.”

I’m basically documenting my life and all of the people in it.

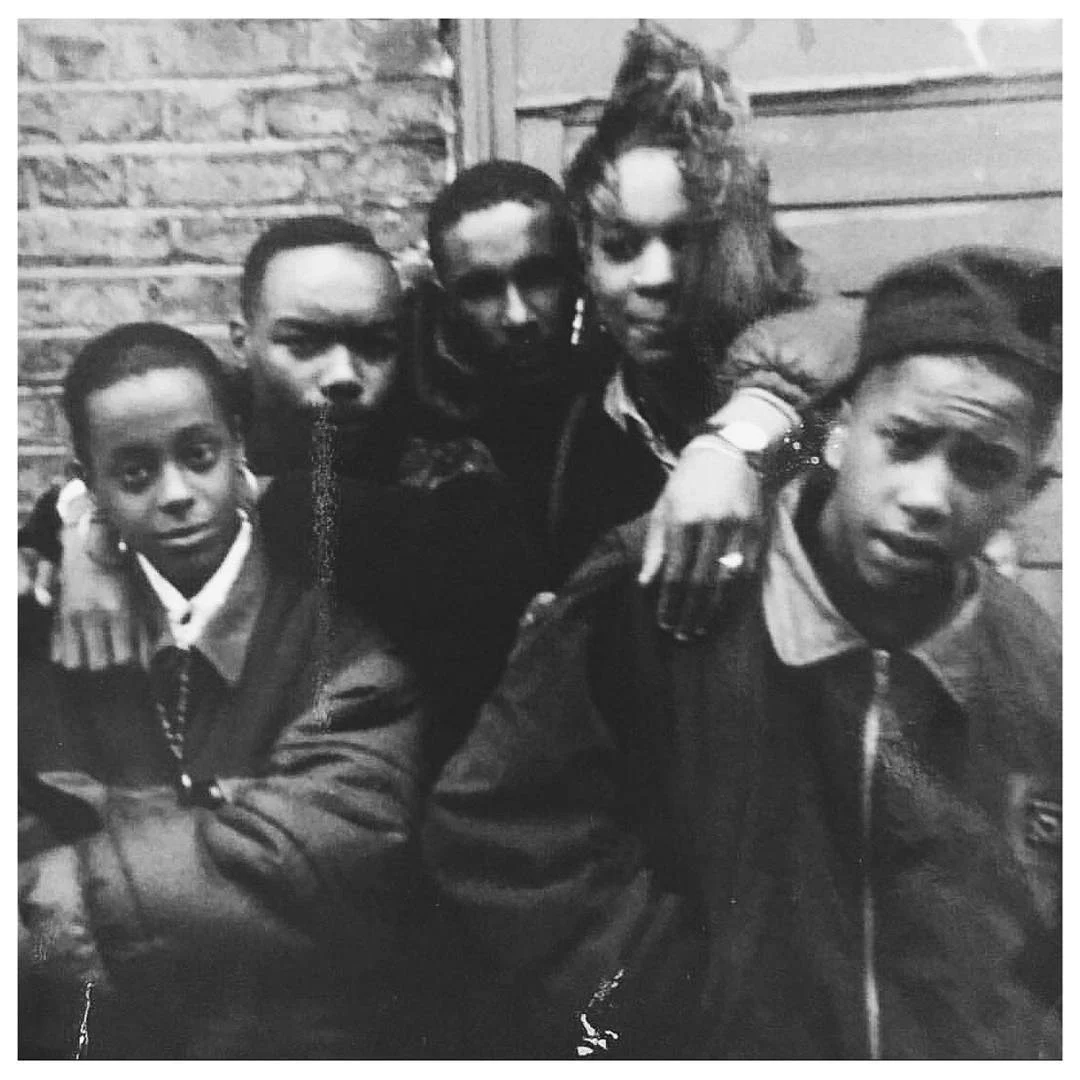

The documentation of everyday moments and rituals led by Black British photographers allows us to look into the communities across the UK in a way that centres just being, rather than aiming to appease a white, mainstream gaze that often projects its own ideas of Blackness. Bernice Mulenga, part of queer collectives Pxssy Palace & BBZ, began their #FriendsOnFilm series in 2016 and what started as just capturing intimate moments, became a concerted effort to centre London’s young Black and Brown queer communities. “I unknowingly created the series to document my surroundings, the places I went and the people I used to hang out with. As time went on, I started to understand what I was sharing and why I was doing it,” they tell me. The significance of Bernice’s project is already profound in the present, especially for young people exploring their sexual identities. However, the power of their work lies in its permanence and providing younger audiences with cultural ancestors who can look at the work and dive into the past and see themselves. “I was essentially doing it for myself. I didn’t see the people I was surrounded by being showcased, I didn’t see regular people in photography. I’m basically documenting my life and all of the people in it,” they add.

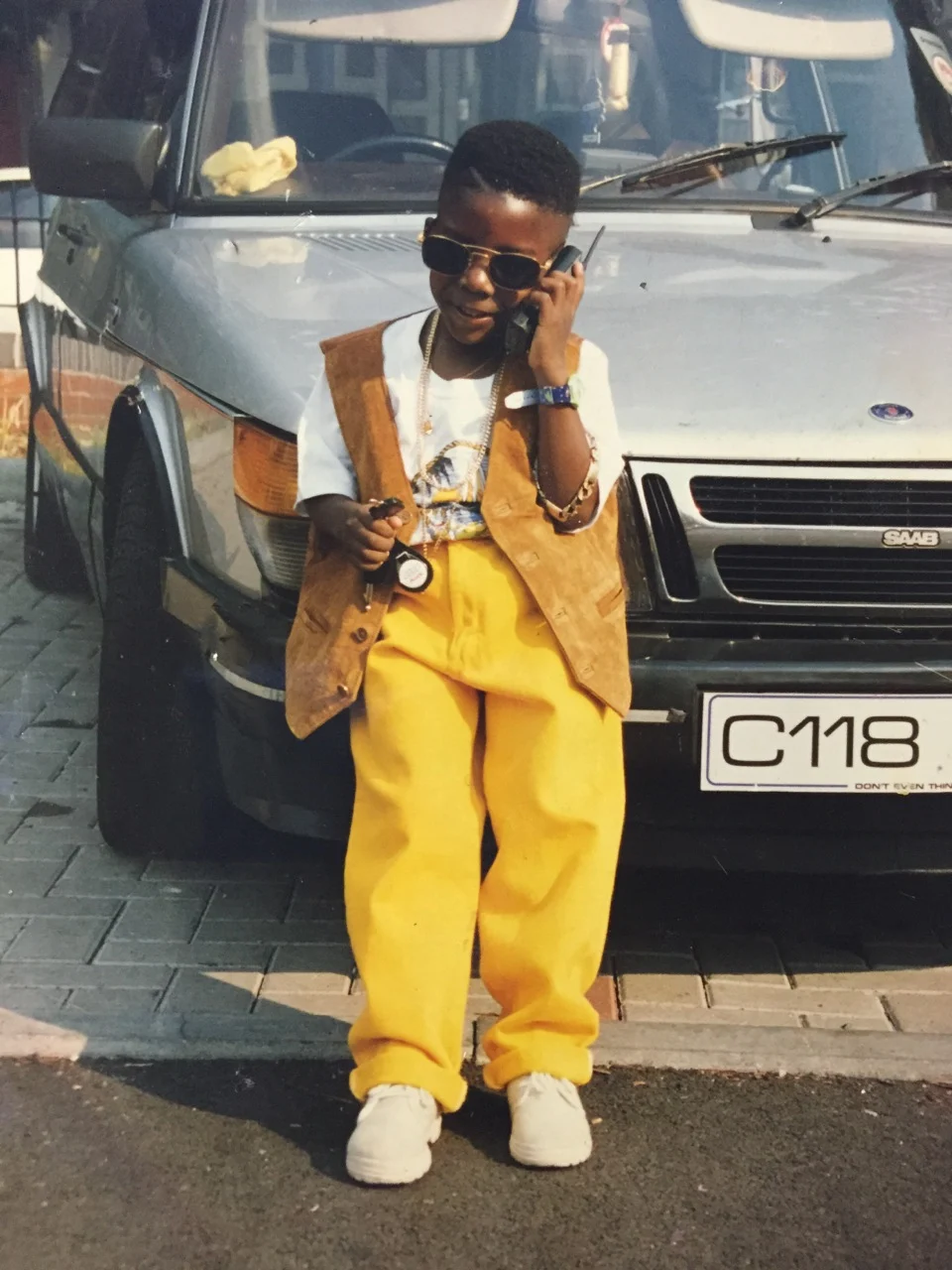

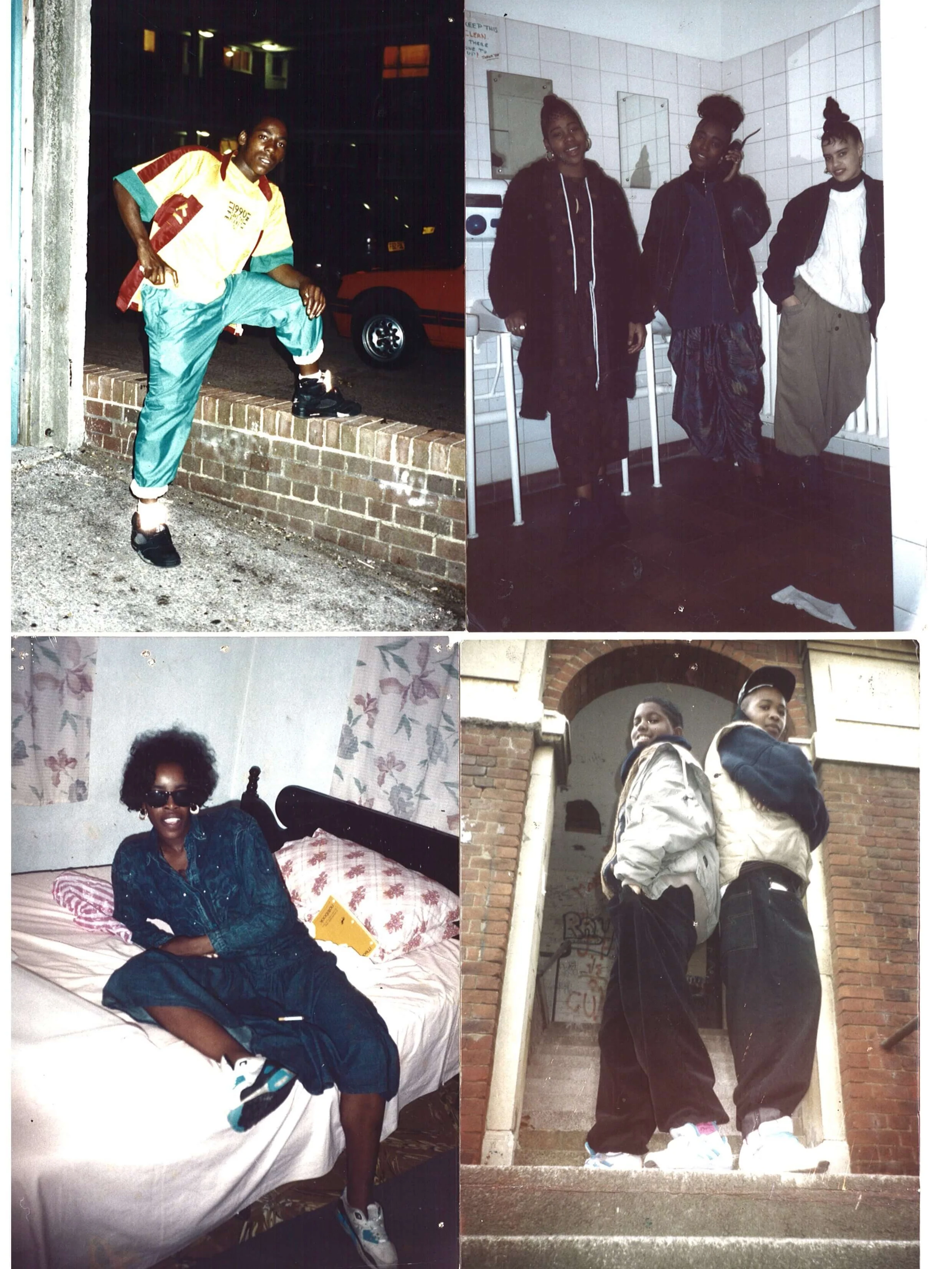

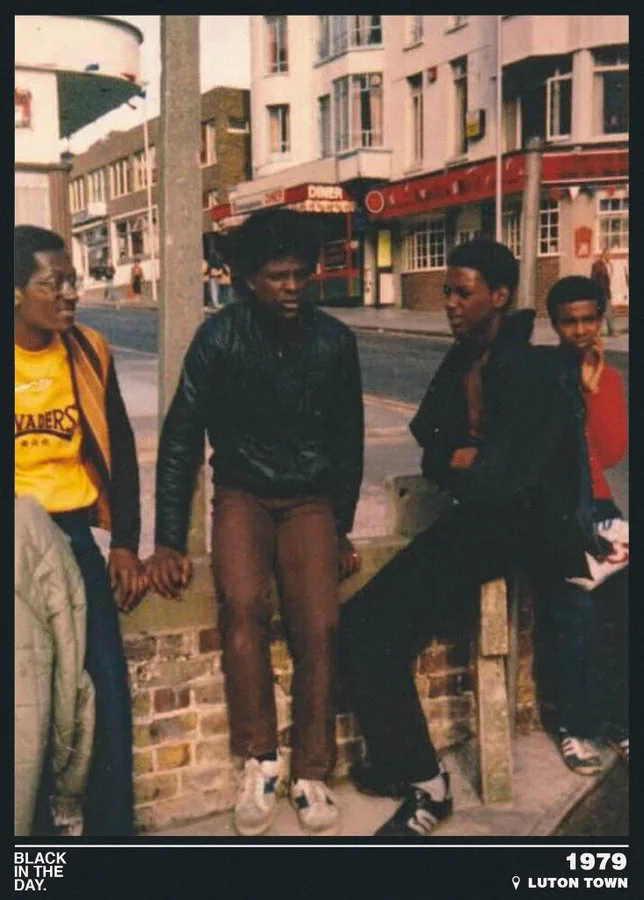

It’s a sentiment writer, designer and curator Angela Phillips shares, who founded the online archive Rudeboys and Rollups. She says that her goal is to acknowledge the early innovators of UK street culture whose names have been lost to time. Blackness and the many expressions of it have often been suppressed throughout modern British history, whether that’s by the media, government policies or something as recent as gentrification. “I didn’t set out to be that one person who was documenting, it started off as a passion project to be honest,” Angela says. “There are so many images that we bring out from family albums and so many stories behind these that I feel like we can tell the story behind a particular piece of clothing that is far more deep-rooted than just liking a particular type of fashion,” she continues. “Even when it comes to wearing our Sunday best, it’s something that’s more entrenched than just fashion, it goes back to the way we were raised. We were taught to wear our clothes with pride. That feeling that emerges when a memory is evoked cannot be replaced.”

A lot of us are hoarders and that in itself is a form of archiving.

Black In The Day, comprised of Tania Nwachukwu and Jojo Sonubi, is both a physical and digital archive in the traditional and colloquial sense. Since 2016, they’ve asked people to submit images from their family albums to help build a physical and digital archive — an ancestry.com of sorts. Funnily enough, I submitted an image taken at my first birthday party which featured my uncles and father dancing together. The image was posted on Black In The Day’s Facebook page and it led to me reconnecting with a cousin I hadn’t seen or spoken to since I was a young child. That in itself is the power of collective archiving, aided by tools that social media have provided which allow us to connect with family members halfway across the world.

One of the assumptions made with regards to the history of Black people in Britain is that the archives don’t exist or for whatever reason, are inaccessible. That’s something Angela Phillips disagrees with. “It’s actually there. There are so many people having impromptu conversations who find themselves going into their wardrobes and pulling something out from twenty years ago. A lot of us are hoarders and we don’t even know it but that in itself is a form of archiving, we just don’t see or call it archiving,” she says. Perhaps that speaks to how memory survives through the aural and oral retelling of our histories, whether that’s cultural, communal or familial. This rings especially true for a group of people who have often been denied access to institutions that allow for history to be on display.

The record collection my parents passed down to me, which features soul, funk, R&B, reggae and rap from the 70s and 80s is a sonical archive in itself that allows me to dive back in time and understand on a much richer level how they celebrated life in London in their twenties. More than twenty years later, those memories survive through the work I carry out by documenting Black music in Britain and its history. The hope is that in twenty years time, young people will look back at the work of Adama, Bernice, Black In The Day and Rudeboys & Rollups and see how their cultural ancestors came of age.

The trinkets that we hoard which no longer hold much cultural relevance aren’t relics of bygone eras. Given our penchant for nostalgia, those items we hoard are more accurately echoes of the past that survive through a communal effort to preserve Black British history at a time when our status as citizens couldn’t be more precarious. “There’s space for all of us to document our culture,” says Angela. “I just want our stories to be told accurately, and the more voices we have doing that helps build a stronger sense of collective Black identity. There’s no limit to our culture.”