These days, it seems anyone with a social media account and enough audacity can call themselves a curator, a title once reserved for those operating in the loftiest art-world spaces. While purists bristle at the co-option of the term, curator Barnie Page has come to welcome it. Here, he explains how the corruption and evolution of the term could give the industry a much-needed shake-up.

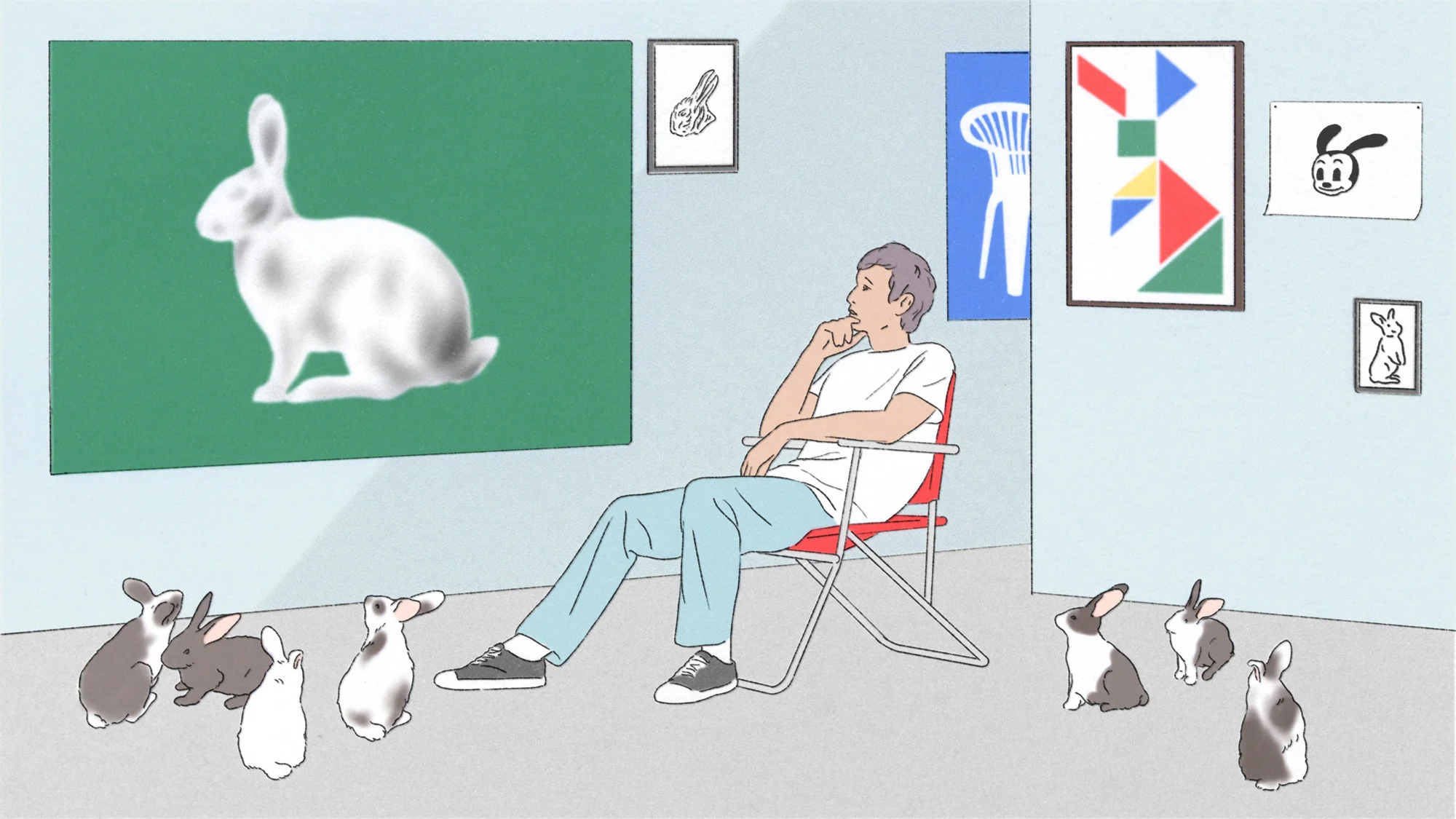

Illustrations by Lucas Burtin.

The job title of “curator” is no longer limited to a specialist position within a cultural institution. It now seems that anybody with the ability to compile existing things can be one, too. From restaurant menus to playlists, listicles to Instagram feeds and shopping “edits,” all sorts of miscellany claim to have been curated. There is even a beef jerky brand called The Curator. I, like other professional curators, have been guilty of dismissing this phenomenon as an example of late-capitalist, Zoomer linguistic vandalism. But putting aside my inherited artworld snobbishness, I can’t help but believe the recent proliferation of curators could in fact be a good thing.

In 2008, Hans Ulrich Obrist, artistic director of the Serpentine Gallery and the world’s best-known and most prolific curator, published A Brief History of Curating, a collection of interviews he conducted with a roster of the 20th century’s most important curators. In the introduction to his interview with the late Swiss curator Harald Szeemann, Obrist writes of how Szeemann saw himself as a “ausstellungsmacher,” or maker of exhibitions—“simultaneously archivist, conservator, art handler, press officer, accountant, and above all, accomplice of the artists.” When I first read this interview many years ago, I was an intern in an artist’s studio and organizing exhibitions in my spare time. This passage struck a chord with me for its recognition of the solid foundation of ancillary labor that constitutes the role of a curator, yet goes mostly unseen.

The absorption of the word ‘curating’ into everyday speech perhaps signals the democratization of a notoriously inaccessible profession within a notoriously inaccessible industry.

In the 10-plus years I’ve worked in the world of contemporary art, I have never had a job with the word “curator” in its title. But despite this, I still see much of my work—writing, graphic design, publishing, art collection management, project management, art consultancy, art handling, assisting artists etc—as curatorial, and consider myself a curator. It could be that my understanding of a curator’s remit is broader than some might like to believe. But I maintain that the title has always come with a somewhat nebulous set of responsibilities, and it is therefore apt for me to use it as a catchall when asked what it is that I “do.”

The origin of the English verb “curate” is the Latin verb “curare” which means “to take care of.” This word initially made its way into English as the noun “curate,” referring to a clergyman who assists a priest in the pastoral care of parishioners. This noun later evolved into “curator” and developed the more generalized meaning of being a guardian in an institution, but it wasn’t until the mid-17th century that the word came to be used in reference to the care of artworks and objects.

In the 1960s, contemporary curators including Harald Szeemann and Lucy Lippard were proponents of the emerging field of conceptual art, in which artworks can be characterized by their prioritization of concept over physical form. (Lippard charted and described the emergence of this “dematerialization” in her seminal 1997 book “Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object,” a book that remains a mainstay of MFA reading lists to this day.) To Lippard, Szeemann and others, curating was not only a profession, but also a creative practice. They turned curating into an art form in its own right through pioneering thematic exhibitions in which, like conceptual artworks, the overarching concept was paramount, and artworks almost served as illustrations of the curators’ ideas. Probably the most venerated example is Szeemann’s 1969 exhibition at the Kunsthalle Bern, “Live In Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form,” the first major exhibition of post-minimalism in Europe. The new forms of art-making exhibited, including conceptual art, land art, and arte povera, provoked such outrage among the public and critics that Szeemann resigned from his directorship and became an independent curator.

The legacy of these curators lives on and can be seen in the curatorial practices of contemporary curators such as Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Cecilia Alemani, and Zoé Whitley. Today, curating is broadly understood to mean the act of organizing existing material with a level of criticality to offer new perspectives on the world. It is considered as valid an expression of subjectivity as art-making. Even if we limit our scope to the context of art, the curator’s output is not only exhibitions, it could be an events programme, a text, a publication or a symposium, to name just a few of the infinite possible outcomes.

Numerous articles have been written about the apparent desecration of the sacred practice of curating and many indignant art curators have been quoted within them. In 2020, Andrew Renton, Professor of Curating at Goldsmiths, University of London, said to the New York Times: “Is the end of all of this that the term is so debased that we have to think elsewhere about what to call ourselves?” This is probably how a medical doctor feels about a curator with a PhD who refers to themself a doctor. But given the long-developing linguistic evolution of the word, do we as curators of art have a right to behave so proprietorially?

Given the long-developing linguistic evolution of the word ‘curator,’ do we as curators of art have a right to behave so proprietorially?

The absorption of the word “curating” into everyday speech perhaps signals the democratization of a notoriously inaccessible profession within a notoriously inaccessible industry. It can only be a good thing if an encounter with curating in a new context encourages people from more diverse backgrounds to be attracted to the profession.

The first time the concept of curating caught my attention was also the first time I heard of it outside of the context of a museum or gallery. It was 2005, and I was reading about the music festival All Tomorrow’s Parties. The lineup of each edition was curated by a different artist—not only musical artists, but also comedians, directors, actors and visual artists, from the Yeah Yeah Yeahs to Matt Groening. As a 17-year-old compiling thematic mixtapes and dreaming up my own fantasy festival lineups, the novel application of this lofty word piqued my interest: it seemed to elevate my teenage pastimes to something more highbrow and specialized.

Like art-making, curating can be an expression of one’s subjectivity, and provides a way to share one’s understanding of the world.

Before I began curating art in any physical space, I kept a Tumblr with a friend. At the time, we worked together in a gallery where we had no say over what was exhibited, and the blog was an outlet for our curatorial ideas and desire to organize exhibitions. We each posted artworks that we liked and, through this, we found common interests and developed a collaborative curatorial voice. Together we went on to organize several group and solo exhibitions, and publish artist books and limited editions. Our Tumblr was a repository of the artists we loved as well as a place where we could experiment quite freely (and for free) with combinations of ideas and artworks. I can’t say that I wouldn’t have become a curator were it not for my amateur experience on Tumblr, but it was undoubtedly instrumental in my professional growth.

Having worked as an assistant to the British conceptual artist Ryan Gander for several years, I’m a supporter of his enlightened view that everyone, in some sense, is an artist. In a 2012 interview with the Guardian on the occasion of his solo exhibition “The Fallout of Living,” he spoke of living as a “creative act.” “In the way that you put things on your mantelpiece, or the clothes that we wear, or any number of decisions we make of how to sweep a room – we all do it differently,” he explained. “That creativity is embedded in just living.”

Like art-making, curating can be an expression of one’s subjectivity, and provides a way to share one’s understanding of the world—whether it’s expressed through contemporary art, a social media feed, a menu, or a mantelpiece. We now have an overwhelming amount of information at our fingertips but limited time and attention span. It follows then that more curators are appearing in non-art fields, bringing in some much-needed order and making sense of the noise for us.