Against the backdrop of our bland, serious reality, High Femme Cinema has created a whole canon of films that embrace everything girly. With the “Barbie” movie about to hit the big screens, writer Anna Bogutskaya explores this world, charting its playful rise from Marilyn Monroe to “Legally Blonde” and beyond. Think handbags, think sequins, think boyfriends as accessories, and above all, think pink.

GIFs by Aliina Kauranne

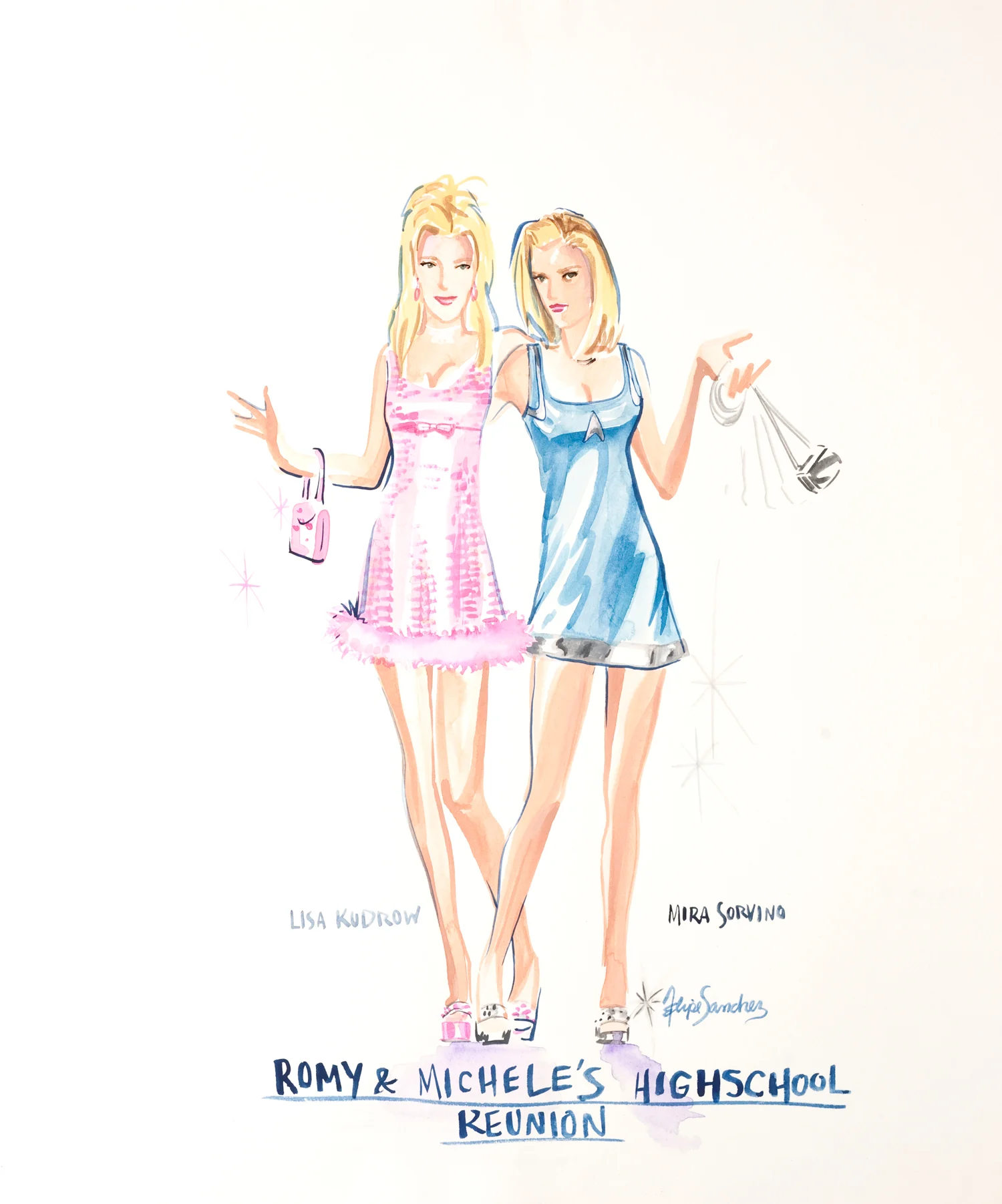

Romy and Michele are ready to go out. The former, wearing a lacquered red coat and cheetah-print corset, and Michele, a cerulean coat with feathered collar and cuffs. This is “Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion” (1997), one of the emblems of high femme cinema and an oft-quoted comedy classic. “I can’t believe how cute I look”, says Romy to herself. “Don’t you love how we can say this to each other and we know we’re not being conceited?” Love this for Romy, Michele and for everyone watching them love themselves.

The furor surrounding Greta Gerwig’s upcoming release “Barbie” is shining a spotlight on a canon of hyper-saturated, buoyant films that gives priority to female leads, their interior lives and the worlds they build for themselves. It’s high femme cinema, baby, and it’s no longer a guilty pleasure. Like many explicitly feminine-coded things, these movies—the likes of “Legally Blonde” (2001), “Clueless” (1995), “The House Bunny” (2008), “Josie and the Pussycats” (2001), “Down with Love” (2003), “13 Going on 30” (2004), the aforementioned “Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion” and, earlier in cinema history, “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes” (1953), “How to Marry a Millionaire” (1953), “Funny Face” (1957), “What A Way to Go” (1964)—have often been dismissed as fluffy, superficial and unserious.

The dreamed, hallucinatory feminine worlds that these movies present are made for the girls. They indulge in the ritual of being a woman, celebrating its seriousness and its frivolity. High femme cinema luxuriates in girliness, glamor and playfulness. They are a kaleidoscope of lighthearted, silly fun, fluffy and shiny textures and bright colors.

Fashion is important, both narratively and visually. In these films, it is not a function-only affair, but a core part of how characters express their personalities. The closet is the central element of these dream houses. Crucially, these films do not look down at the ritual of putting on make-up and selecting an outfit. Both “Clueless” and “Legally Blonde” open with their leads getting dressed. It’s a process. “The notion that this is a superficial pursuit is cast aside,” film critic Christina Newland says, noting that the films “also acknowledge that the act of getting ready, creating this image of a glamorous woman, is labor.”

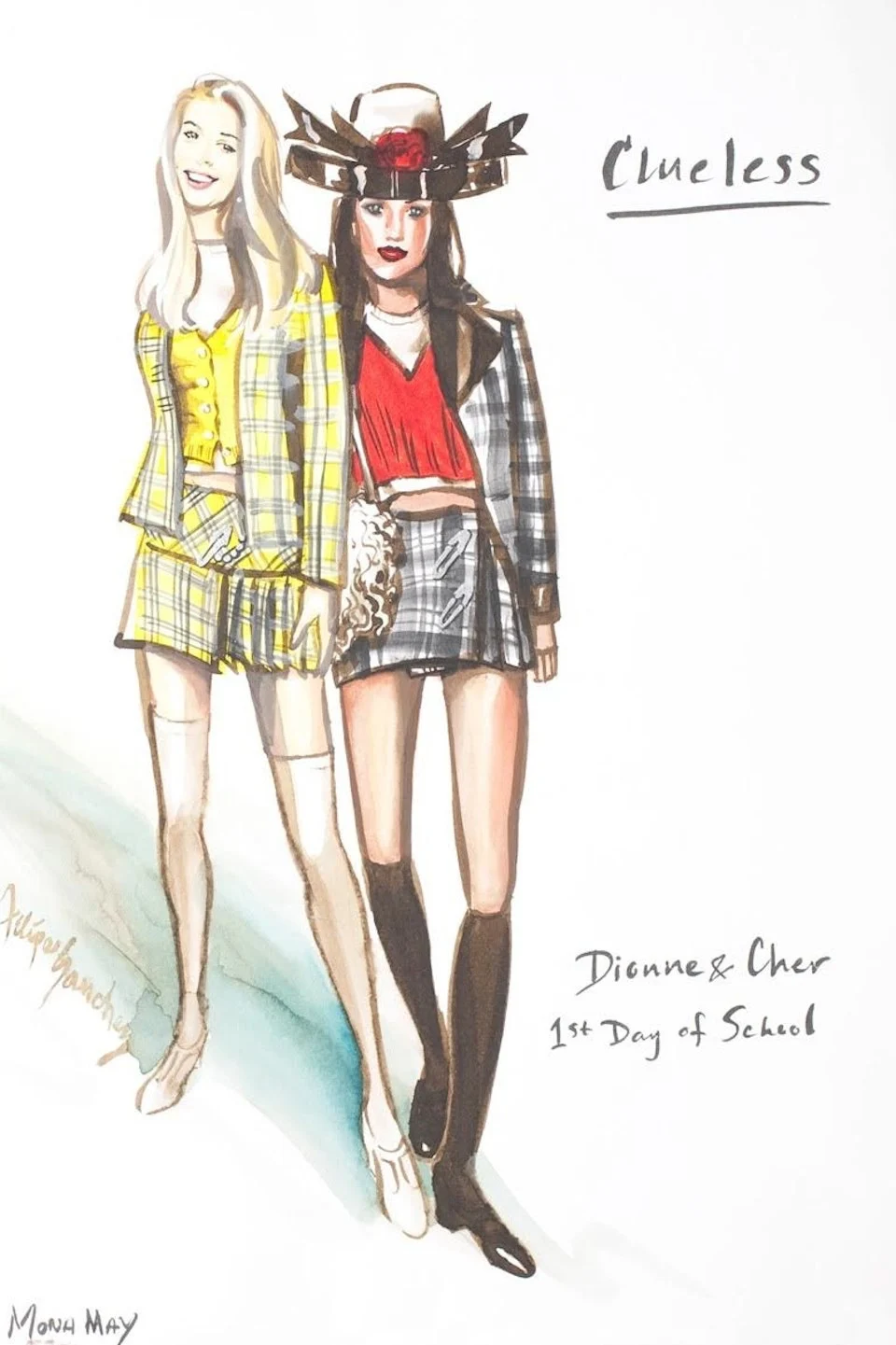

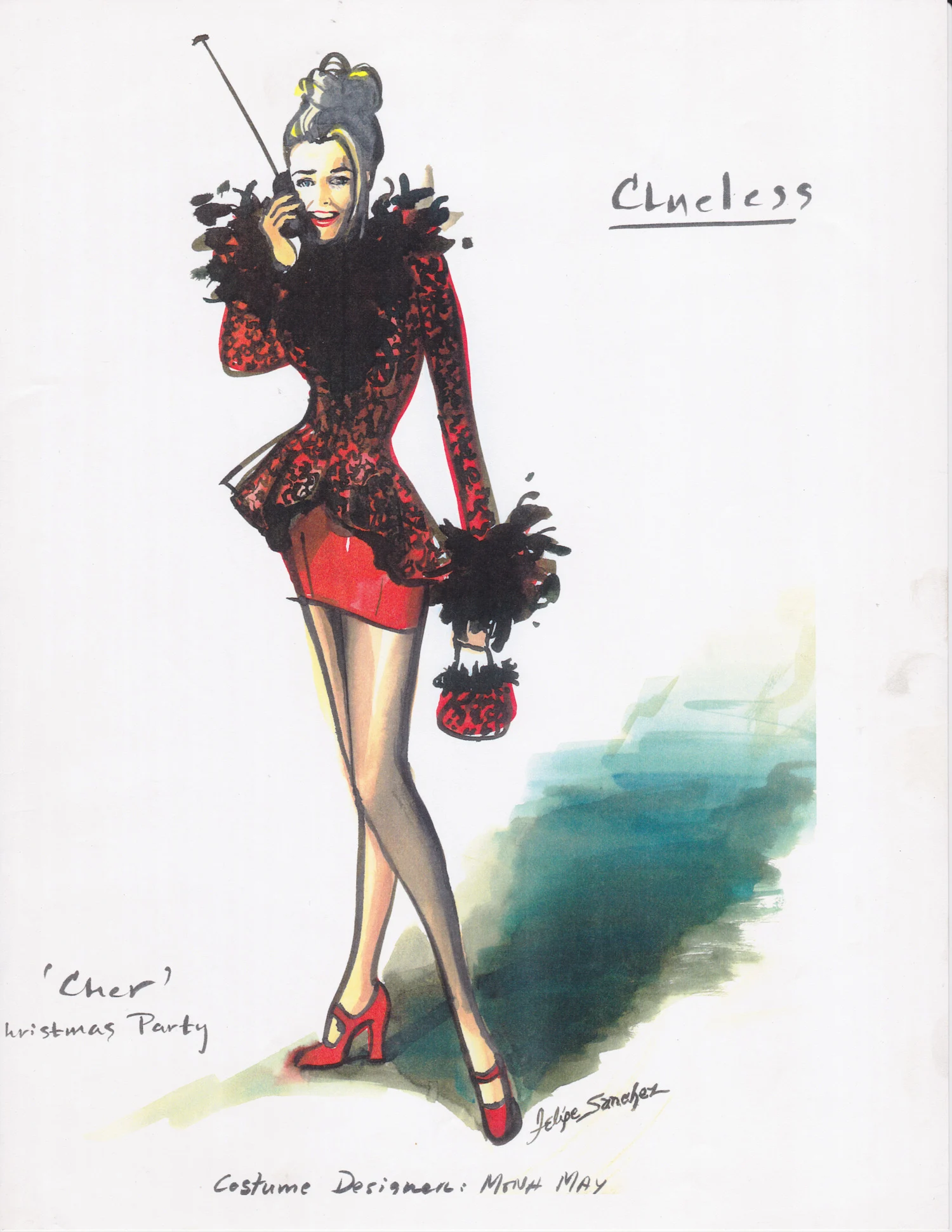

We meet Elle Woods of “Legally Blonde” through her meticulous grooming process. The gentle brushing of her blonde mane. French manicured nails. Leg shaving (with a pink razor, of course). Her desk is a mess of old copies of Vogue and nail polishes. In “Clueless”, Cher has a computer programme that matches her outfits for her, warning her off any mismatches. The first outfit we see her in is the yellow tartan miniskirt and blazer, a timeless choice that has become emblematic of the film. The film’s costume designer Mona May, who has also worked on over 40 titles, including “Romy and Michele”, “The House Bunny” and “Enchanted”, spoke to me from Berlin. May recalled how the color clicked almost instantly for her and director Amy Heckerling: “It wasn’t until she put the yellow on that she was the sun, and we knew that she was the center of the world.” These film’s costumes have consistently become the most recognisable elements of the films. At their reunion, Romy and Michele stand up to their now-grown high school bully, changing into their home-made silvery-blue, empire-waist mini dress and pink A-line minidress with a marabou trim. Every Halloween, I spot at least a couple of Romy and Michele’s.

Costume design is an avenue to achieve a sense of timelessness. For May, that’s always the aim: “In both ‘Clueless’ and ‘Romy and Michele’, I was trying to create a world that didn’t exist. I created a fashion that wasn’t on the street yet.” At the time when both films were made, grunge was the trend, and garishly girly outfits were out. May was one of the first costume designers to mix thrifted items with haute couture brands, making sure that the teenagers in “Clueless” didn’t come across as “snooty models running around high school.” While the girls in “Clueless” are affluent and stylish, Romy and Michele are fashionistas with menial jobs, so they design and make most of their clothes themselves. They wear shiny, colorful gym wear, color-coordinated high feels, fruit-shaped jewelry and bedazzled everything. “Bedazzling in the 90s was huge,” May reminds me, “it personalizes everything and was the funnest thing to do on the set.” The camera glides across the clothes and make-up, the nail polishes and shoes (the instruments of femininity) making sure we take in all the detail, and admire the effort of looking like Romy and Cher, like Dionne and Elle. Visually, these films prioritize “extravagant details, like flower arrangements, wallpaper, shoes, matching hats and handbags”, creating a curated clutter. In “Clueless”, legendary cinematographer Bill Pope used the camera as a fashion eye, shooting long shots of the girls walking, lingering on the shoes.

Much like the films themselves, the protagonists of high femme movies are routinely underestimated and dismissed. Wanting to appear more successful than they are, Romy and Michele fib that they invented post-it notes, and are humiliated by their former bullies. In “Party Girl” (1995), Marie has to practically beg to be hired as a library clerk because she’s deemed unserious and untrustworthy. When Elle decides she wants to go to Harvard Law, she’s gently laughed out of her advisor’s office. When she arrives, the other students (not a bold color in sight on campus) derisively call her Malibu Barbie. But when tasked with a series of goals to hit, Elle doesn’t miss. The extremely beige and brown room of Harvard Law admissions officers are dumb-founded as to why a fashion major would want to study law, but they can’t help but let her in. Looking back at the characters she’s helped bring to life, May reflects that “they are all dreamers. They are girls who are curious about life. They look at what can be improved about themselves. Their true core is to help.” High femme films relish in shared joy. They want to spread the joy they feel, not gate-keep it. See: bend and snap.

High femme movies tend to be comedies, itself a genre that’s often cast aside as frivolous. May notes the difference of working with comedy actors: “The comediennes approach the characters in a different way. They are more open, they don’t need to look so perfect all the time.” Marilyn Monroe, one of cinema’s most recognisable blondes and a perennially underappreciated comedienne, casts a long shadow over high femme cinema. Elle’s douchebag boyfriend dumps her, reasoning that “If I’m going to be a senator, I need to marry a Jackie, not a Marilyn”.

Pink is almost the guiding force. It’s a conscious statement and it’s an anti-dark, anti-grey, grim self-seriousness.

There is, of course, the pink of it all. Writing in his book “Color on Film”, film critic Charles Bramesco points out: “Even within something as subtle and aesthetically pure as color, there’s still an embedded politics, sometimes explicit and sometimes buried in subtext.” While pink started off as masculine color, in the mid-19th century it started to become associated with women and femininity. Valerie Steele, the editor of “Pink: The History of a Punk, Pretty Colour”, charts how “pink became an expression of delicacy, as well as froth”. While it was associated with high fashion in the early 20th century, by the 1950s, pink was synonymous with hyper-femininity. The gendered color divide of “pink is for girls, blue is for boys” was cemented by American post-war marketing. “Barbie” deliberately incorporates the widest spectrum of the color, from the brightest to the palest pinks. Gerwig and production designer Sarah Greenwood have made Barbie Land into an extravagantly artificial world, ungoverned by the laws of physics, grounded in 1950s soundstage musicals and a childhood memory of where Barbie lives. Newland adds that “pink is almost the guiding force. It’s a conscious statement and it’s an anti-dark, anti-grey, grim self-seriousness. It’s saying, ‘we don’t need to be a series of muted palettes in order to say something about the world.’”

With “Barbie” coming up, the ultimate girly movie pitted on release day against the ultimate boy movie, “Oppenheimer”, there is a giddy joy in the air. The global “Barbie” fever has not that much to do with nostalgia, and everything to do with aesthetics. Since she was invented in 1959, Barbie has been an emblem of femininity, a nostalgic comfort as well as a reminder of an unachievable beauty ideal. Now, in her first big-screen, live-action outing, Barbie has become the perfect vessel for reclaiming the idea of the bimbo, as Newland notes: “Barbie is a perfect metaphor because she’s the ideal of white beauty standards. She’s the image of the most vapid, dumb blonde but also, look at all her jobs! She’s got a boyfriend who’s essentially an accessory.” In Gerwig’s hands, though, Barbie can get acrylic nail extensions and have an existential crisis. In high femme cinema, the unthinkable is possible: two things can be true at once.

High femme cinema is anti-sleaze. There is an overwhelming earnestness, every frame dripping with sincerity. This is the world women make for themselves, where hyper femininity is an expression of themselves instead of a performance for someone else. The conflict occurs when this makeshift reality clashes with the rest of the world. Thankfully, all the bimbos get their happy ending: Elle graduates as the valedictorian of her class, Romy and Michele open up their candy-colored boutique, Cher makes a deeper connection with her friends, and Barbie, well, she gets everything.