Since fleeing Iran in the face of war at age seven, Ashkan Honarvar has never felt directly connected to any of the places he’s lived in. His collages meditate on those years in Iran, but rather than trying to explore war in a literal way, or violence itself, his work explores human nature, and our response to that violence. He tells writer Dalia Al-Dujaili how his work ruminates on things that affect people worldwide: on the sense of being uprooted, on identity, and on the complex connection between people and nature.

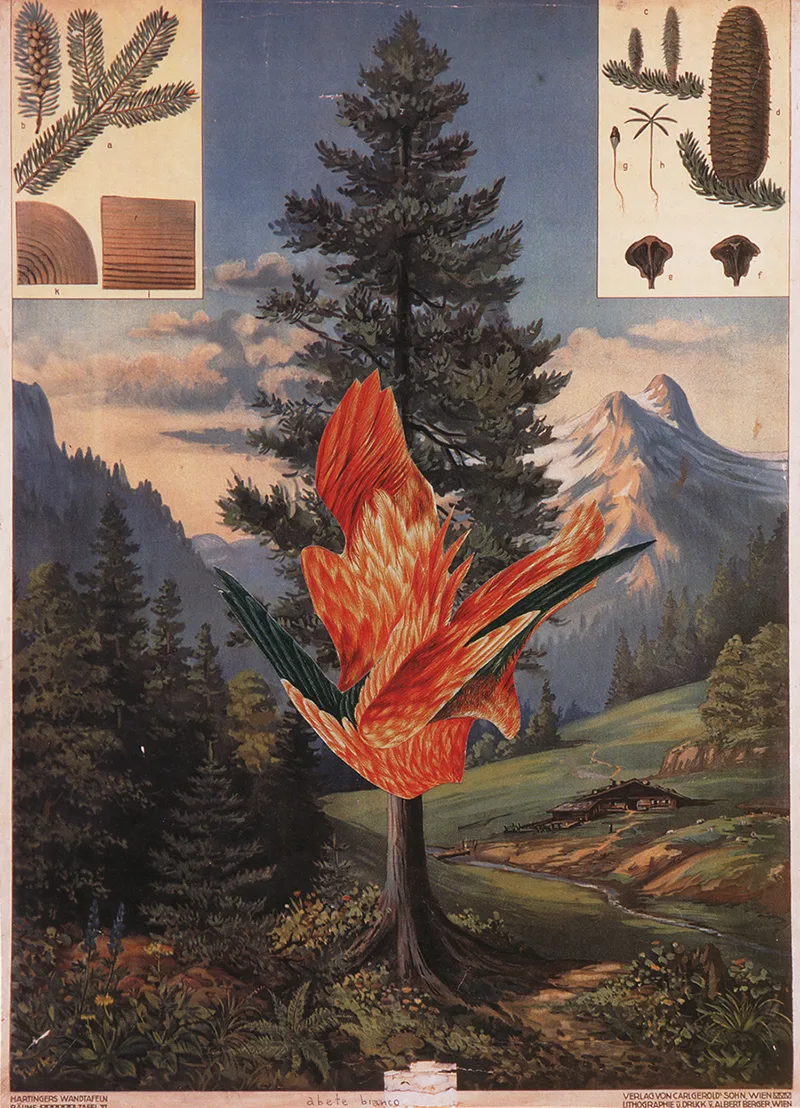

The popular aesthetics of war and conflict rarely include the natural or botanical worlds. Organic matter is often traded for artillery, machinery and cement—bar, of course, blood. Ashkan Honarvar isn’t interested in leaning into traditional depictions of war. Instead, he attempts to deconstruct the meaning of war vis-a-vis his Persian upbringing.

Ashkan left Iran at the age of seven when the country was facing a bloody invasion by neighboring dictator Saddam Hussein. The artist tells me that as a child, most of his drawings depicted battlefields, influenced by watching the war through his television screen. “As a kid, I thought the coolest thing was the machinery, the tanks,” he remembers.

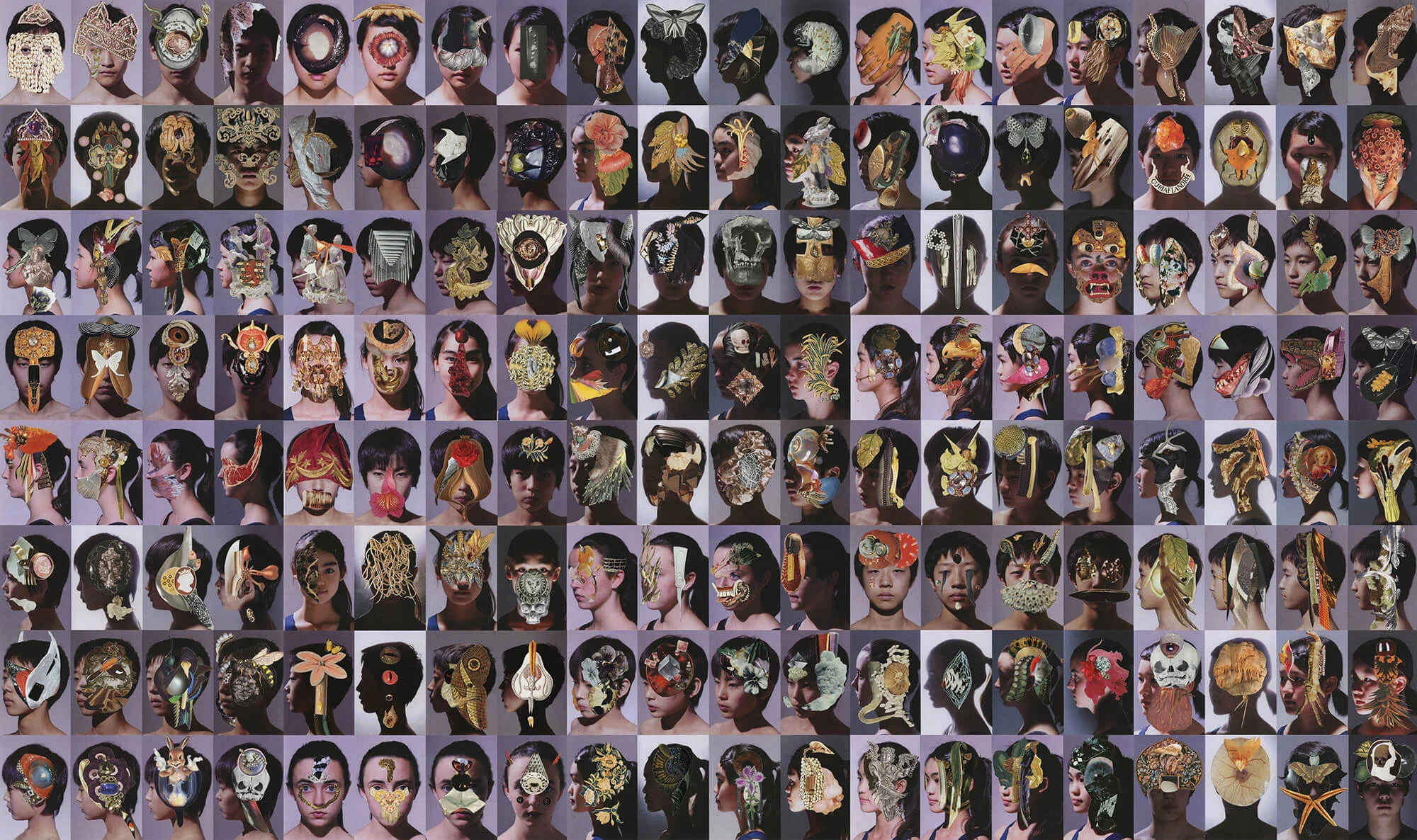

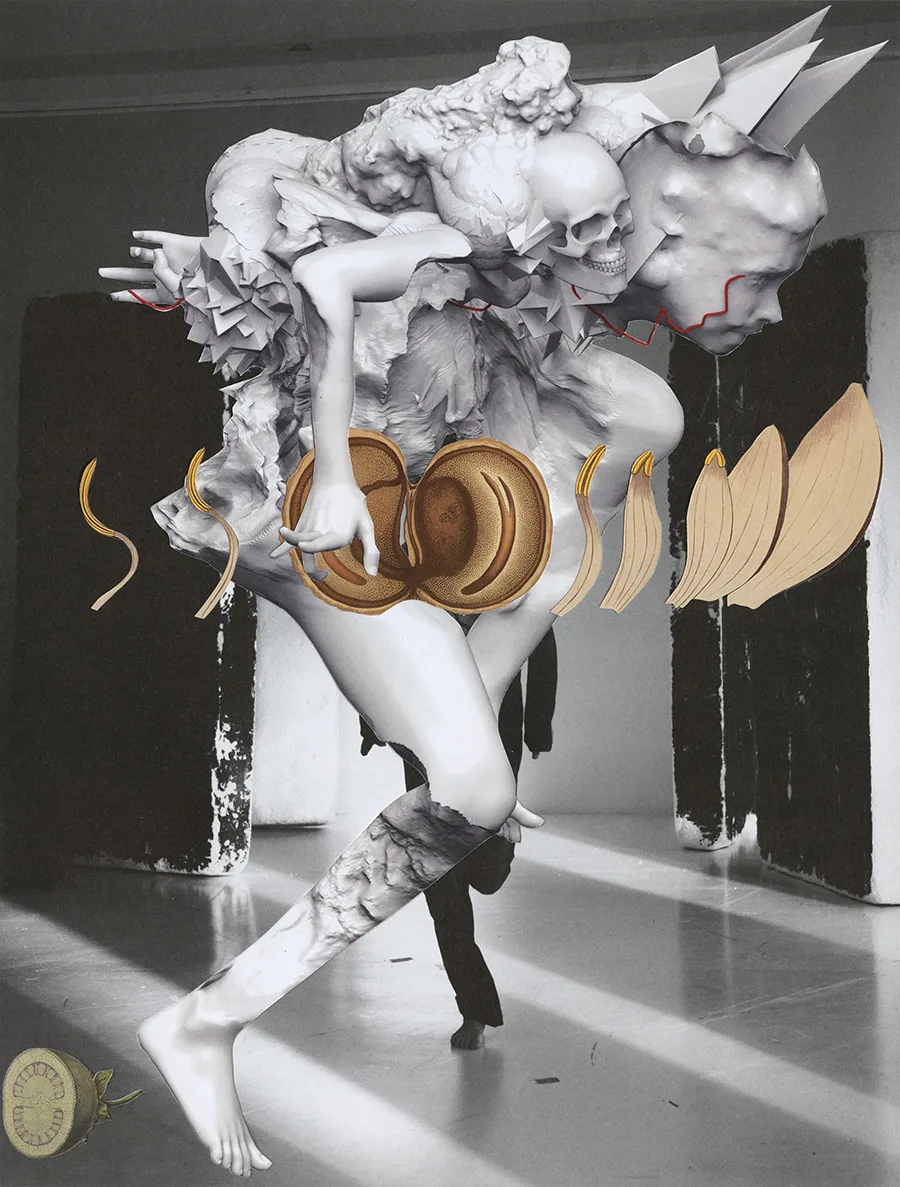

His family fled to the Netherlands, where Ashkan undertook three years of graphic design and four years of illustration, before receiving a two year stipend in Norway to develop an artistic project called “Faces,” highlighting facial disfigurements from war. It was upon completing this project that Ashkan decided that “art is one of the best ways to find answers,” and that “the act of cutting collages for hours on end” was synonymous with meditation.

I never felt that my identity is connected to any one country, so I'm trying to answer questions about us as humans.

Having grown up between Iran, Turkey, and the Netherlands, and now living in Norway, Ashkan has never felt like he belonged anywhere, and in that sense, he also felt he belonged everywhere. “I never felt that my identity is connected to any one of [these countries]. I'm not Persian. And I'm not a Dutch person. And I'm absolutely not Norwegian. So most of my projects have mostly involved me trying to answer questions about us as humans.”

In 2017, Iran’s youth ignited in demonstrations. Over a two-week period, protests spread like wildfire to over 140 cities in every province in Iran. The people of Iran were revolting against their regime, just as they have done more recently. “I remember vividly, living in the Netherlands and seeing all these… shady camera images coming up from people that were maybe younger [than me], and they were getting beaten, they were getting killed,” Ashkan reminisces. “They were fighting for freedom… It was just raw to see them.” The artist was prompted by questions around where he’d come from and he tells me it was the first time that he felt strongly connected to a country he hadn’t grown up in. Both the series’ “The red forest” and “Paradise Lost,” the artist confides, were thus attempts to meditate on those first seven years of life in Iran, “the consequences of leaving your country, the consequences of war, the consequences of other people's choices that have an effect on your life forever.”

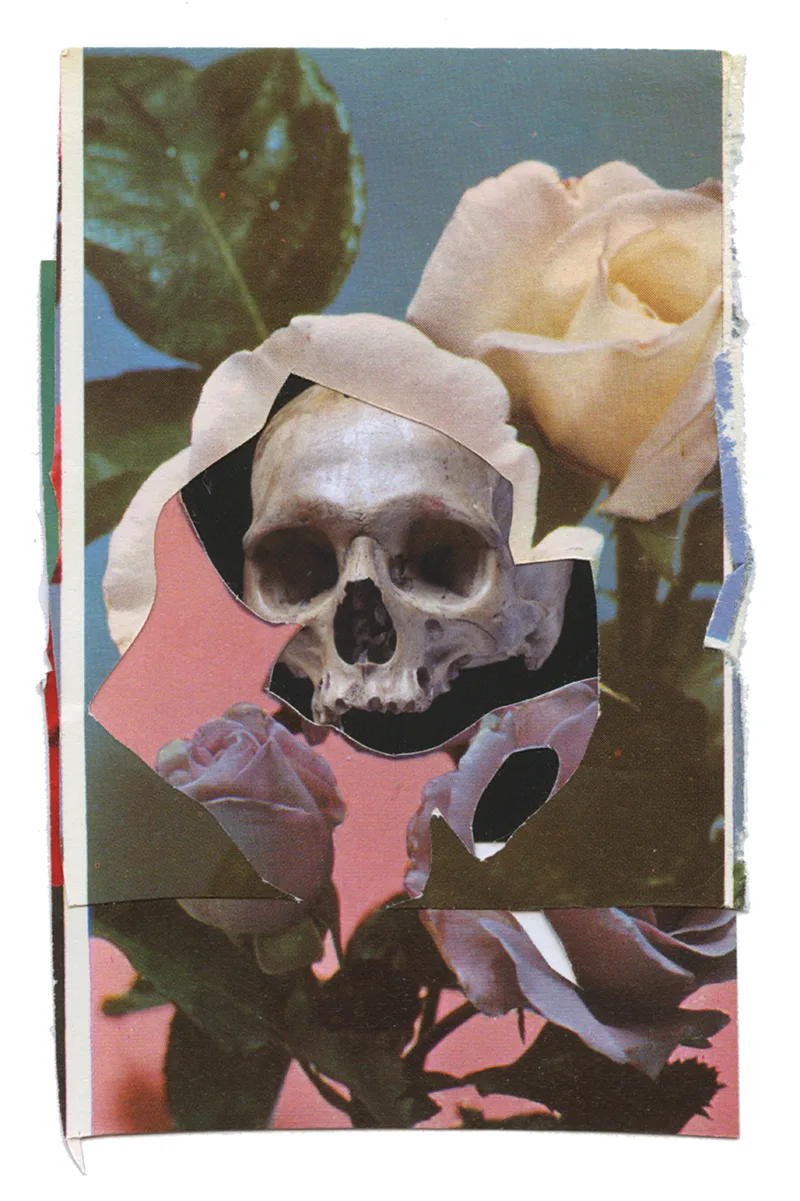

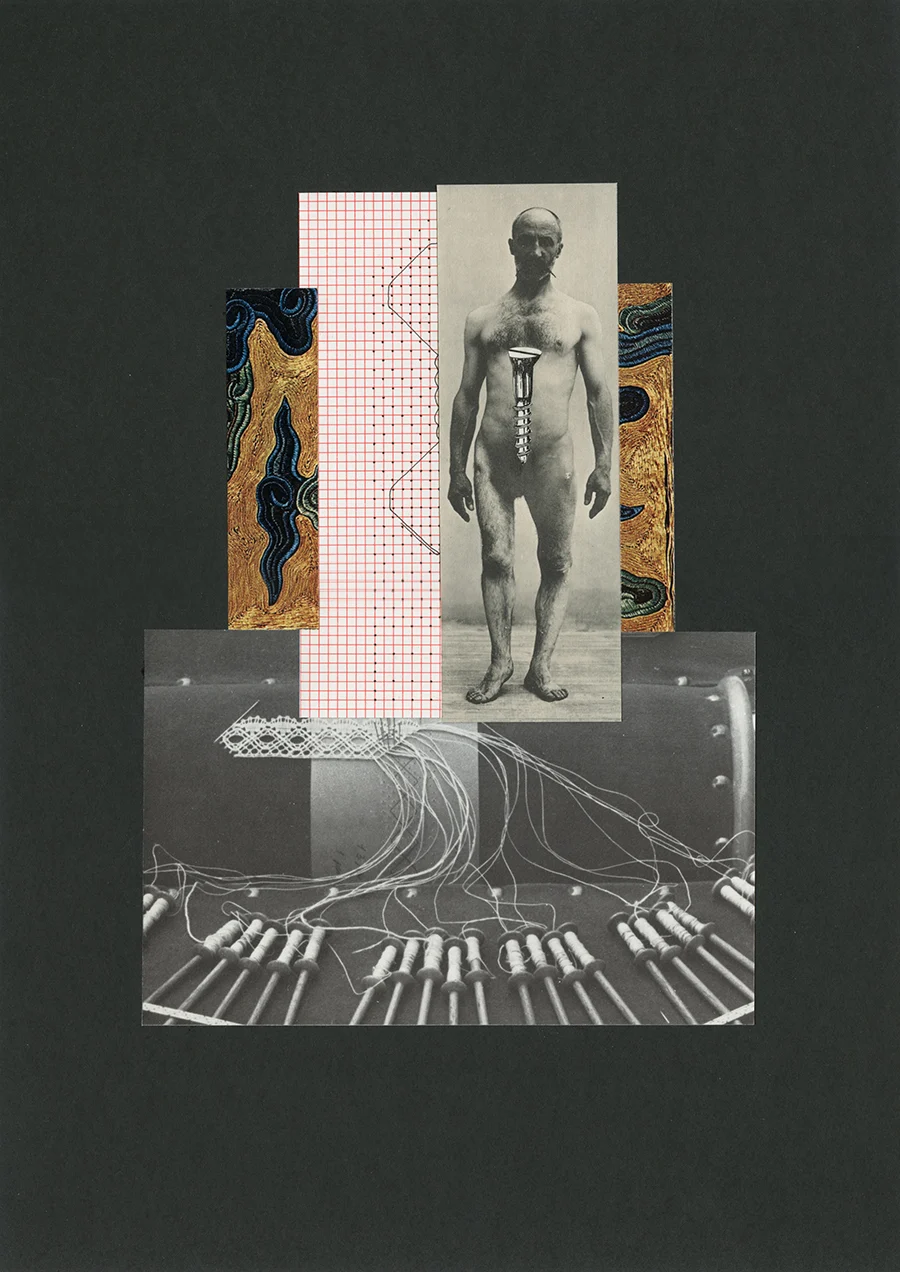

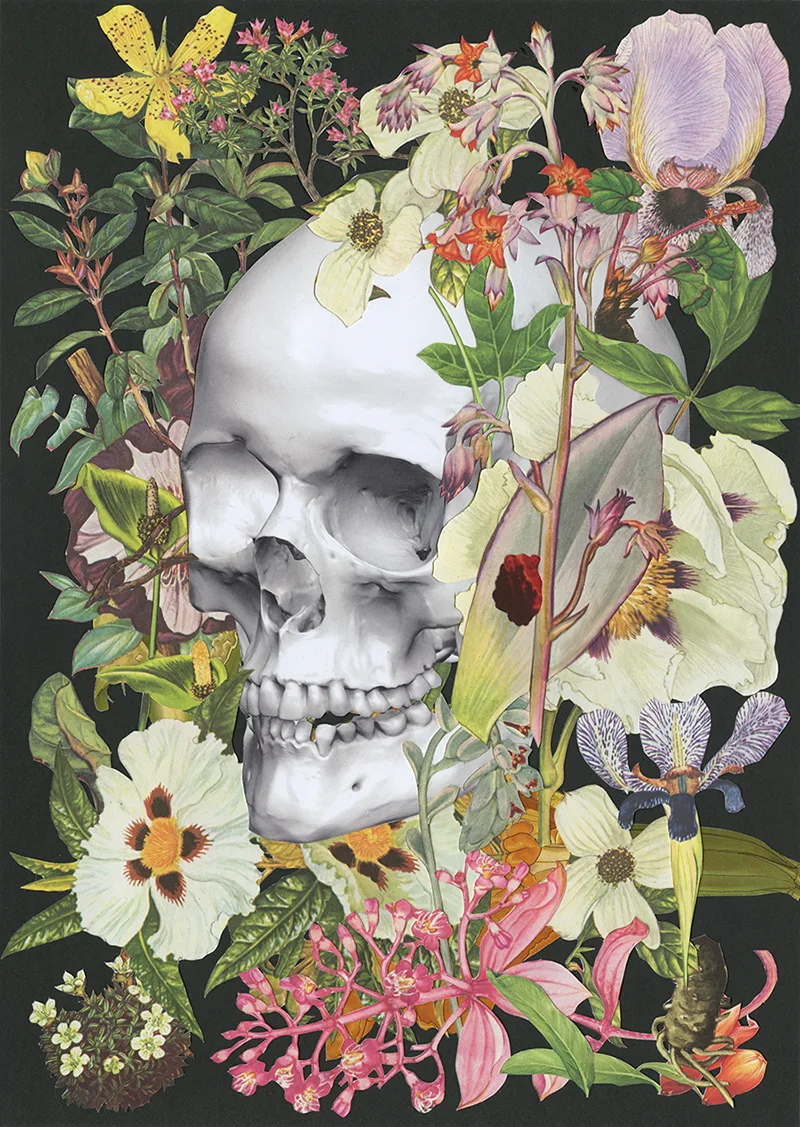

But one would have to stretch the imagination to find literal references to Iran within the works of “Red Forest” or “Paradise Lost.” His work evolves from sources taken from written text like a book or a line from a movie, constantly taking cues from itself in order to propel forward and subsequently morphing into something vastly different from the original text. What is abundant instead is an almost melancholic and methodological approach to nature; vintage botanical and natural reference drawings sit alongside skulls and the anatomy of a body, heavily contrasting the machinery and tanks he was so fascinated by in his youth.

The projects seek to explore the psychological questions raised by war and conflict, “trying to find questions about us as humans and [about] human nature,” the artist tells me, rather than representing acts of violence themselves. Hence, there are also moments where Ashkan gestures the intersection of the mind and the natural world by overlaying retro black and white scenes from a forest or a lake with scenes from a psychological examination on a woman.

One of the things the artist remembers from his first seven years in Iran was his home and its big garden. “And I remember the sirens. I remember we had a bomb shelter in the garden and I remember the vegetation, a lot of flowers. I started writing down and making drawings of all these things,” which then became a manual for the imagery he went onto use. But when choosing the imagery from books to use in his collages, he lets his mind wander. “You don't think about the source material anymore, you just go with the flow.”

Instead of using archival family images, Ashkan references a garden that’s beautiful, but shrouded in looming death symbolically and semiotically, as he remembers his old home. Hence, “Paradise Lost,” John Milton’s epic poem detailing Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden.

Comparatively to many diasporic creatives, Ashkan finds comfort in the lack of reference to an idealized homeland throughout his work. For the diasporic creative, there is power in avoiding literal imagery, because his works can be taken out of context and interpreted to fit into any paradigm where violence is enacted and death flirts with life.

The power lies in “not belonging to a certain religion, not belonging to a certain country. Without sounding too hippy about it,” Ashkan jests, “by not being part of a country or a border, you become part of a bigger thing. And when you become part of that bigger thing, everything is a material.” At the end of the day, as he reminds me, violence is the same no matter where it occurs or who it affects. In that sense, Ashkan Honarvar’s work advocates universality.