Writer Tom Seymour explores the history of the artists working in secret and obscurity behind the Berlin Wall and speaks to curator Sonia Voss about the group of pioneering photographers who redefined ideas of identity and representation, creating a blueprint for the protest movements of today.

Before the fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989, the German Democratic Republic (GDR) insisted on conformity, and systemically demanded its citizens sacrifice everything for the might of the collective. One’s job, diet, clothing and lifestyle were planned and decided by bureaucrats. Patriarchy was pre-eminent. Heterosexuality and gender conformity were rigorously imposed. To step out of the structure defined for you would likely result in excommunication, exile, incarceration or, in some cases, death.

During this time, a group of artists living under the GDR of East Berlin grappled with existential queries on a daily basis. Questions such as, can someone be unique if they are born into a collective? Or how can you express who you are when “personality” is anathema: “asocial”, dangerous, unpatriotic?

To be an artist in the GDR, one had to conform to the dogma of “social realism,” which held that art should be illustrative and optimistic, and should always glorify the solidarity of the working man. To have their art exhibited publicly, or to hope to earn from their work, a GDR artist had to a member of the Verband Bildender Künstler (Association of Visual Artists), a kind of trade union that strenuously regulated the activity of its members. Any art that existed outside of this, that engaged in any way with suggestion, inquiry or experimentation, would remain “for the drawer,” only to be shown to an artist’s trusted circle of friends. Otherwise, the work quickly came to the attention of the authorities. Most often by the GDR’s secret police, the Stasi.

Working in secret, and placing themselves at great personal risk, this loose collective of dissident pioneers developed remarkably creative ways to resist the all-powerful state. Many turned to photography. A new monograph titled The Freedom Within Us, edited by Parisian curator Sonia Voss, explores the work of 16 East Berlin and GDR artists who daringly developed creative ways to express their liberty and singularity. The act of doing so was, by dint of existence, a powerful statement of resistance. The monograph launched alongside a headline exhibition titled Restless Bodies at the 2019 edition of Rencontres D'Arles photography festival in the south of France.

The body became the canvas. It became the work of art.

Interestingly, despite many of the artists on show not being able to socialise or work together, threads and themes appear in their work, particularly in the artists’ use of the body. “The artists would probe the body, whether through its dramatisation, or by ensconcing it in a concealed, self-referential frame,” Voss explains. “They found the normativity of their society unbearable; from childhood on, life was decided by the state. Even trivial details like clothing was decided for you. They were obsessed with finding ways to express themselves, to be different.”

Ute Mahler and Sibylle Bergemann spent their days in public as official photographers for the state-controlled press whilst secretly pursuing their own artistic work behind closed doors. Others, like Manfred Paul, taught at highly-controlled educational institutions, and would create work at night apposite to what he was forced to teach. This included private portraits of his wife taken when she was in labour which gave the impression that she is in the midst of sexual elation.

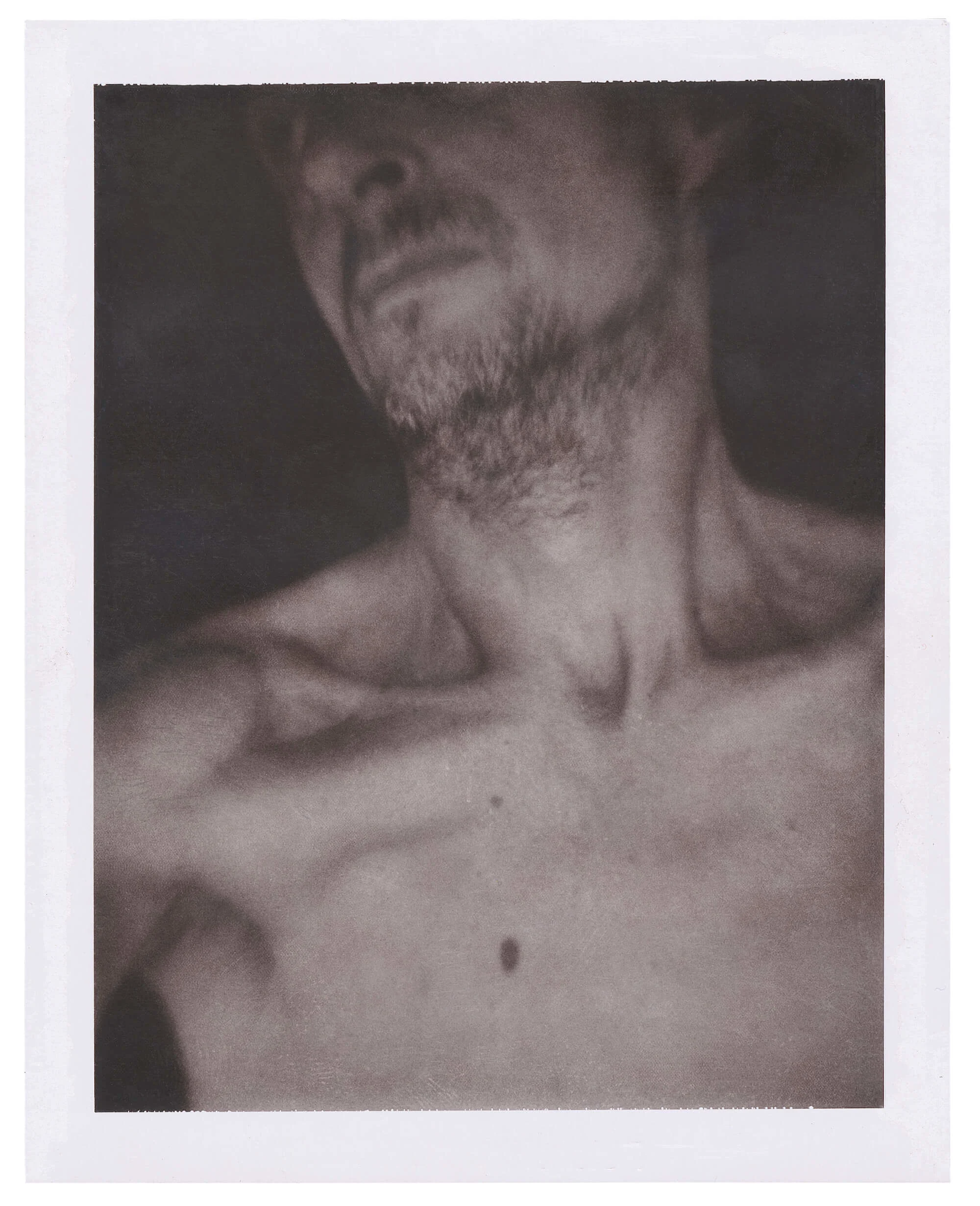

Paul also used a Polaroid camera to create a series of interesting self-portraits that reflect his frustration at not being able to express his true self. “In all my work I am reacting to my own emotional state,” he told Voss. “Shortly before the fall of the Wall I went through a period of internal malaise. Hope and fear. A French friend of mine brought me the camera. I had talked to him about needing to make self-portraits and this was the ideal tool for the project.”

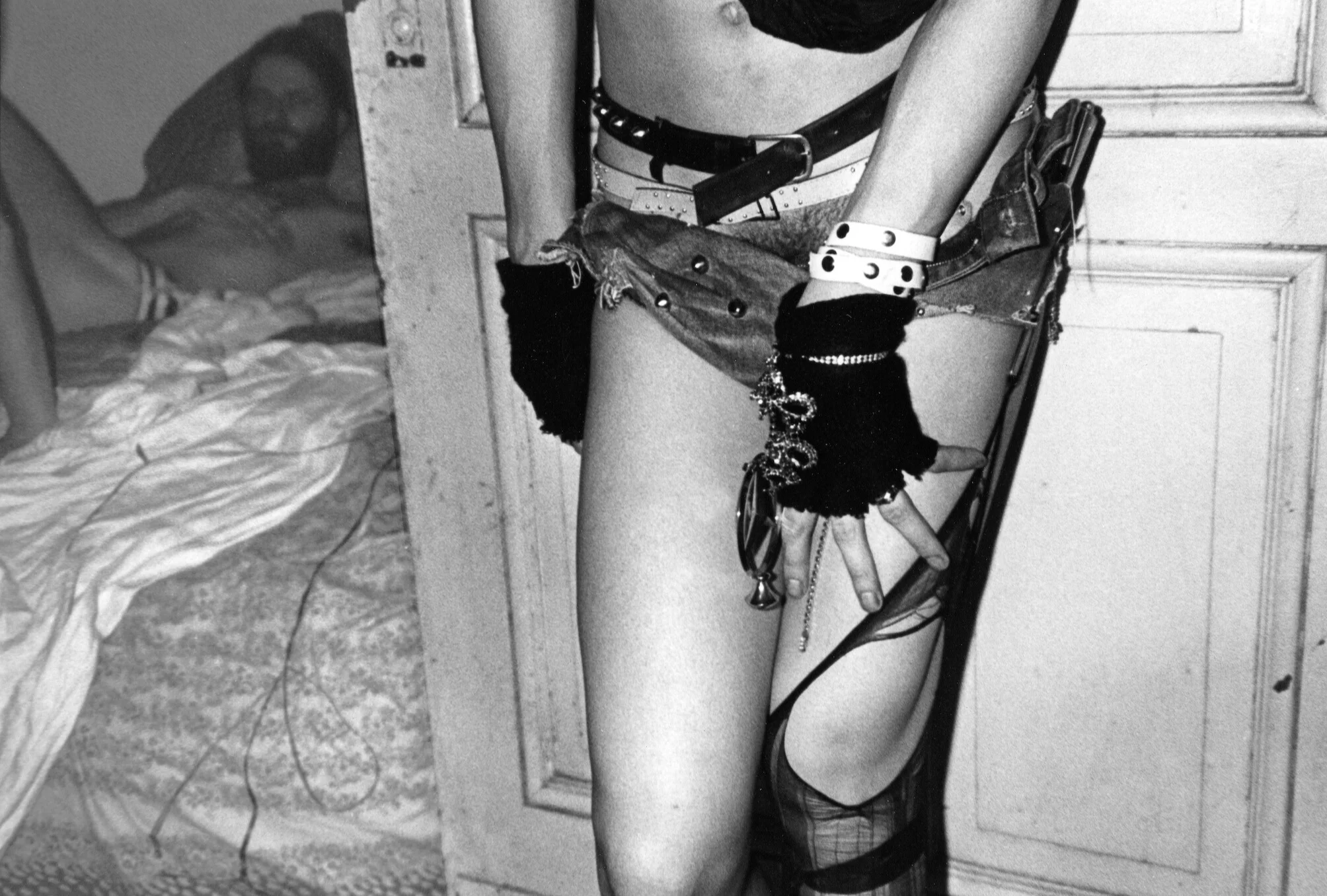

Other artists were less capable of internalising. The monograph also features the extraordinary work of the radical feminist and performance artist Gabriele Stötzer, who chose a more active form of protest and resistance, and subsequently spent a traumatic period of her early-twenties in a maximum security all-female prison.

Stötzer is present at the exhibition in Arles. Now 66-years-old she recalls how at just 23 she spent a year in prison for having initiated a petition against the expatriation of Wolf Biermann. She tells Voss about being sent to Hoheneck Prison (also known as Citadel of Murderers) for one year, surrounded by many women serving long sentences. “Up to that time I had always thought of murder as something male,” Gabriele recounted to Sonia. “They were lesbians, though in the GDR they did not even have a word for that. They were tattooed all over and often engaged in self- mutilation; smashing glass so they could bloody themselves with it. I left prison totally disillusioned about socialist ideals. I was so angry that I talked and wrote about it immediately once I was out.”

The work of Stötzer and her contemporaries formed a “zeitgeist moment,” says Paul Moorhouse, curator of the contemporary portraiture at London’s National Portrait Gallery, over the phone. “Artists used the body as a weapon, but also as a site of experience,” Moorhouse says. “The body became the canvas. It became the work of art.”

After her release, Stötzer was carefully observed by the Stasi. She shows me a series of portraits she took of a young transvestite: a man who craved to live as a woman. I ask about the subject in the photos, who, in a pair of high-heels and make-up, engages with Stötzer’s camera as if set free for the first time. “He had a real problem with his penis and wanted it taken off with an operation,” she says. “He had started wearing dresses in the little town where he came from, and it made him a target.” After the wall fell, the Stasi’s archives were made available to the public, and Stötzer read her file. She realized the man in the exhibition in Arles was also an informant. “I worked with him a lot...I only found out he was talking to the Stasi when I read my file.”

From then on I walked around town with the Leipzig punks.

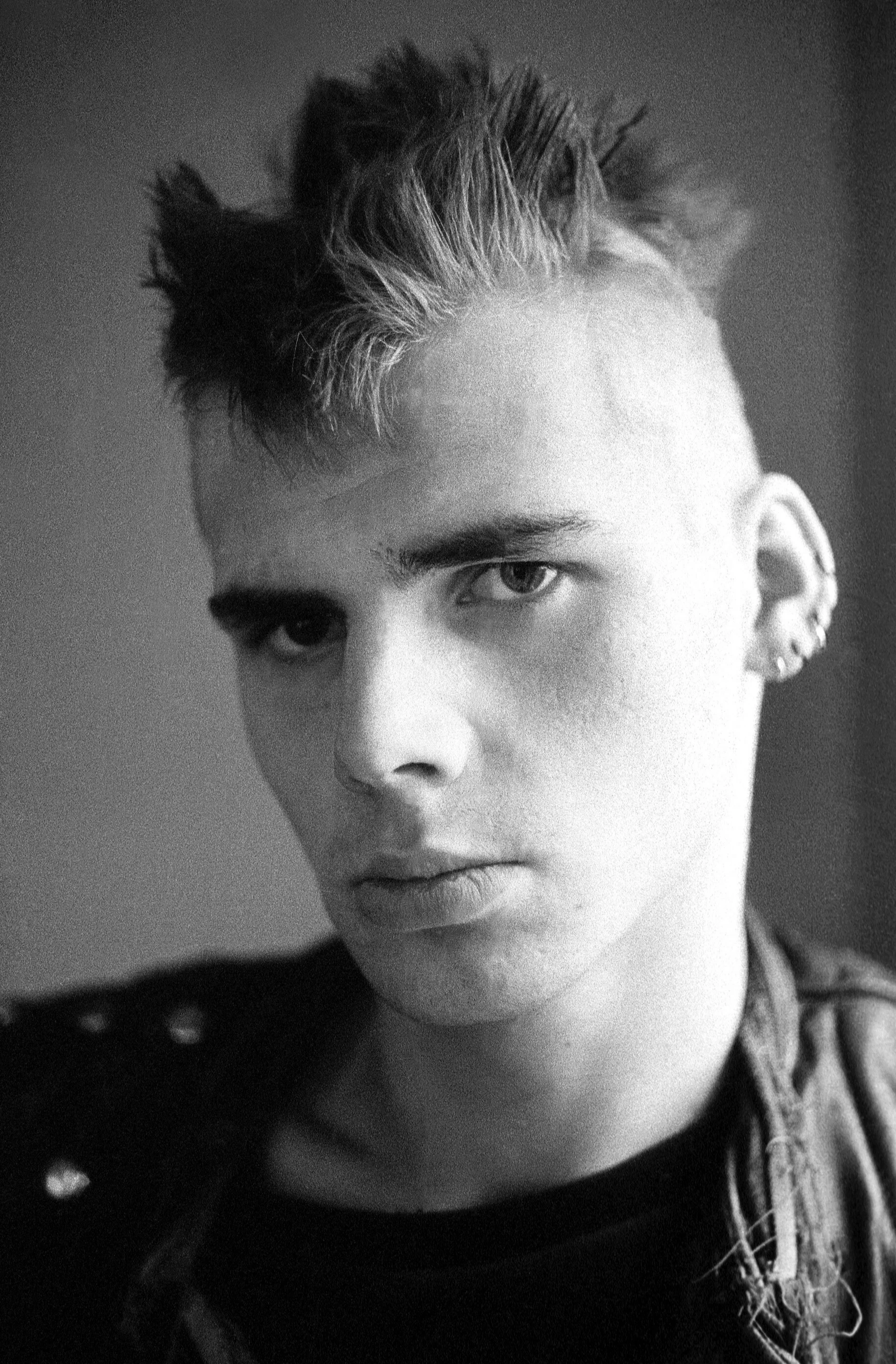

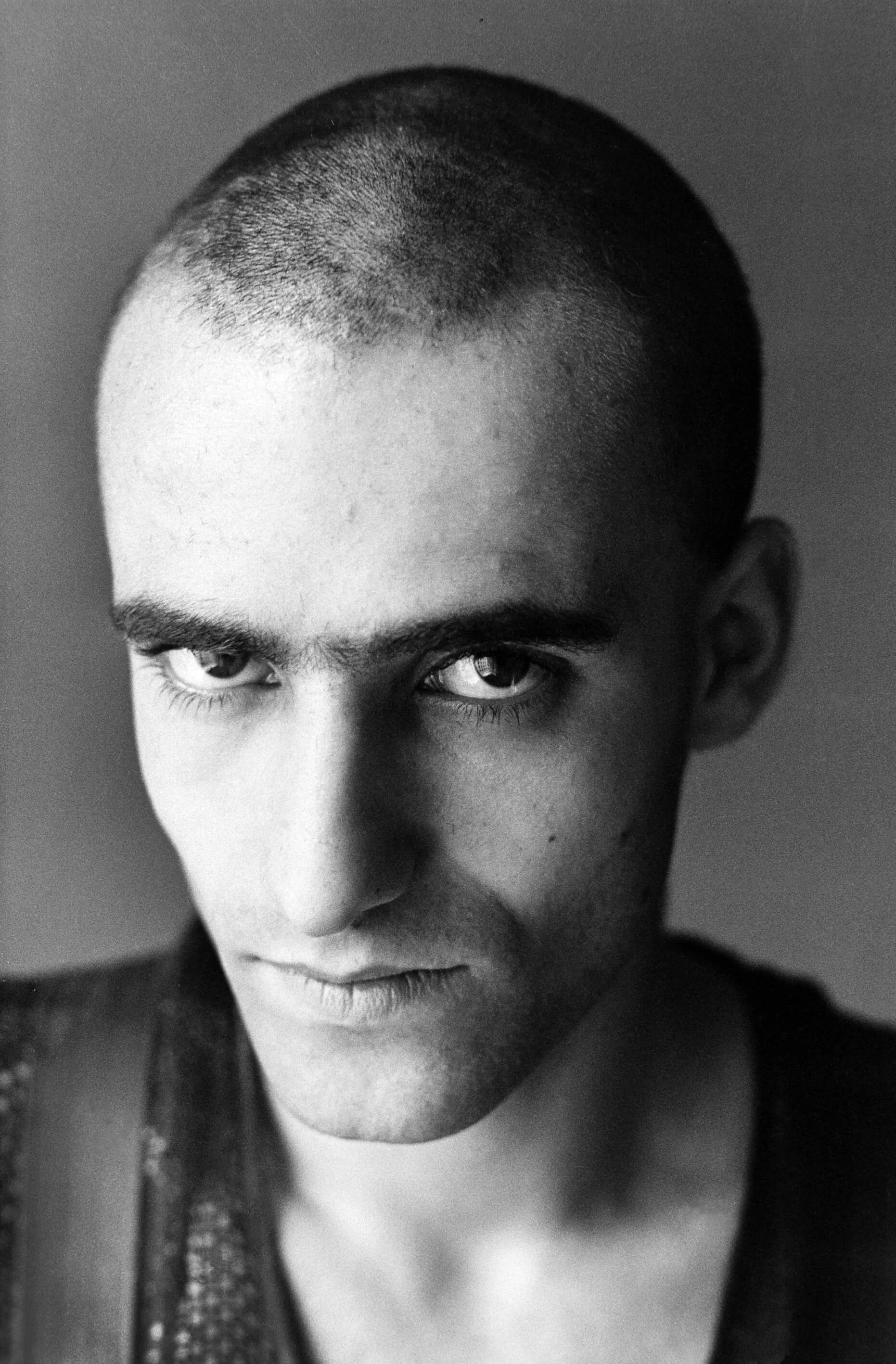

The opening of the GDR’s archives in the early nineties revealed that some of East Berlin’s most committed dissident artists also spied for the Stasi. Voss shows me a series of portraits by Christiane Eisler, a photography student from Leipzig who inverted the austere rules of social realism with her reverent portraiture of the emergent punk scene in the small Eastern German town. “I was living in a damp flat ripe for demolition in the Seeburgviertel. The toilet was in the stairwell, half a floor down. But I had my peace there,” Eisler recounts. “And then they just shuffled right by me—as I emerged into the broad daylight from my back courtyard, I saw them standing there: brown, scruffy figures dressed in leather, a little grumpy and reeking of alcohol and cigarettes. From then on I walked around town with the Leipzig punks.” Among the portraits are startlingly powerful shots of a young punk called Imad, who somewhat resembles Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver. “He was a member of a punk band, and a very committed, very active member of the community,” Voss says. “But he was also an informant.”

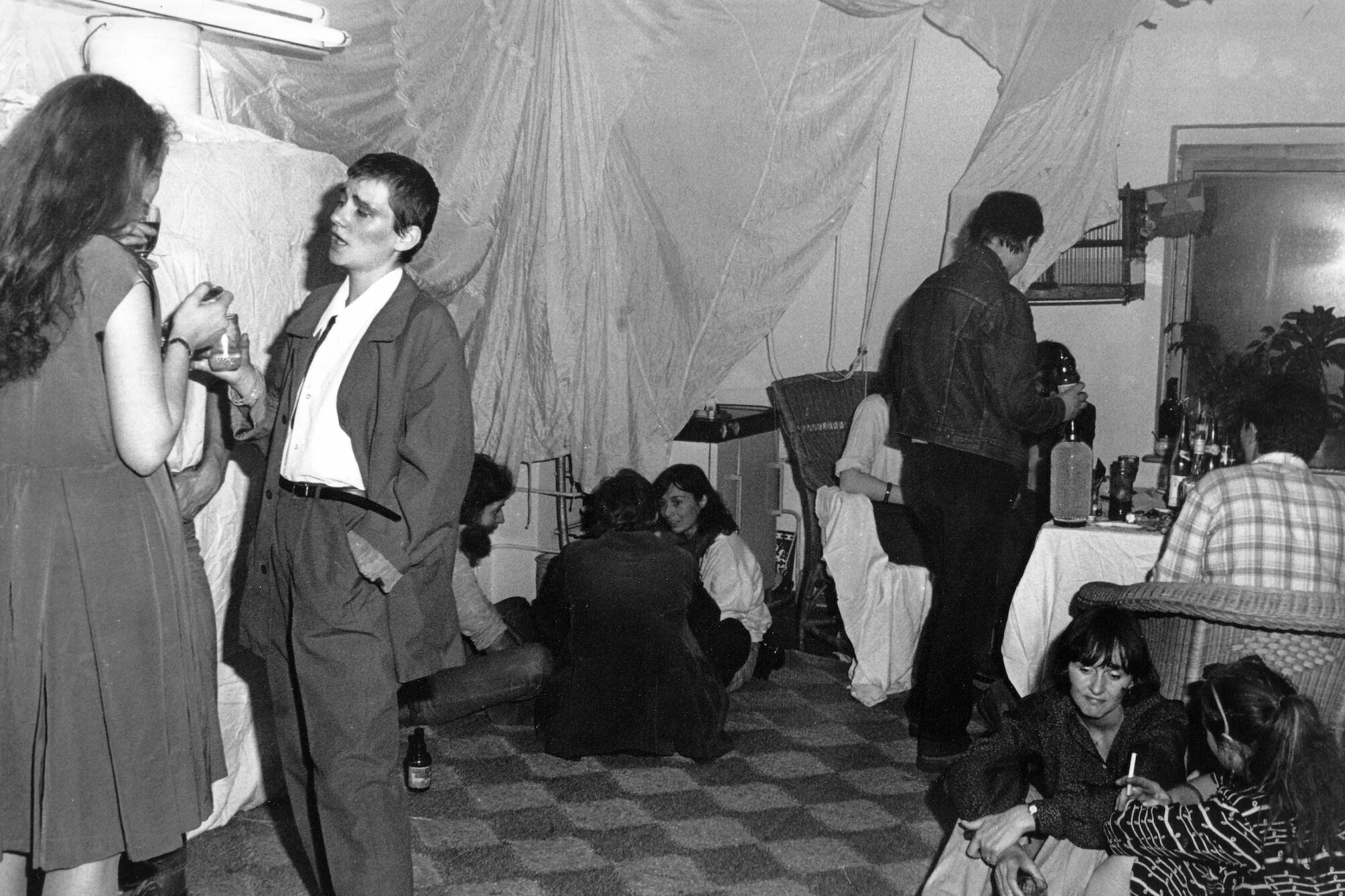

Elsewhere, at nightfall, Frieda von Wild, daughter of Sibylle Bergemann, organized fashion shows as a member of ccd (chic, charmant & dauerhaft) which translates as “Chic, Charming, and Here to Stay.” This was an implicit form of resistance; clothing was decided upon by the GDR. “We showed a mixture of our own designs,” von Wild said of the shows. “Some sewn or knitted by ourselves, some queer garb we dug up in our own or our grandmothers’ wardrobes, and whatever we could fit under the presser foot of a sewing machine: bedclothes made of excellent cotton, or diapers and shower curtains, all the way to foils used in agriculture.”

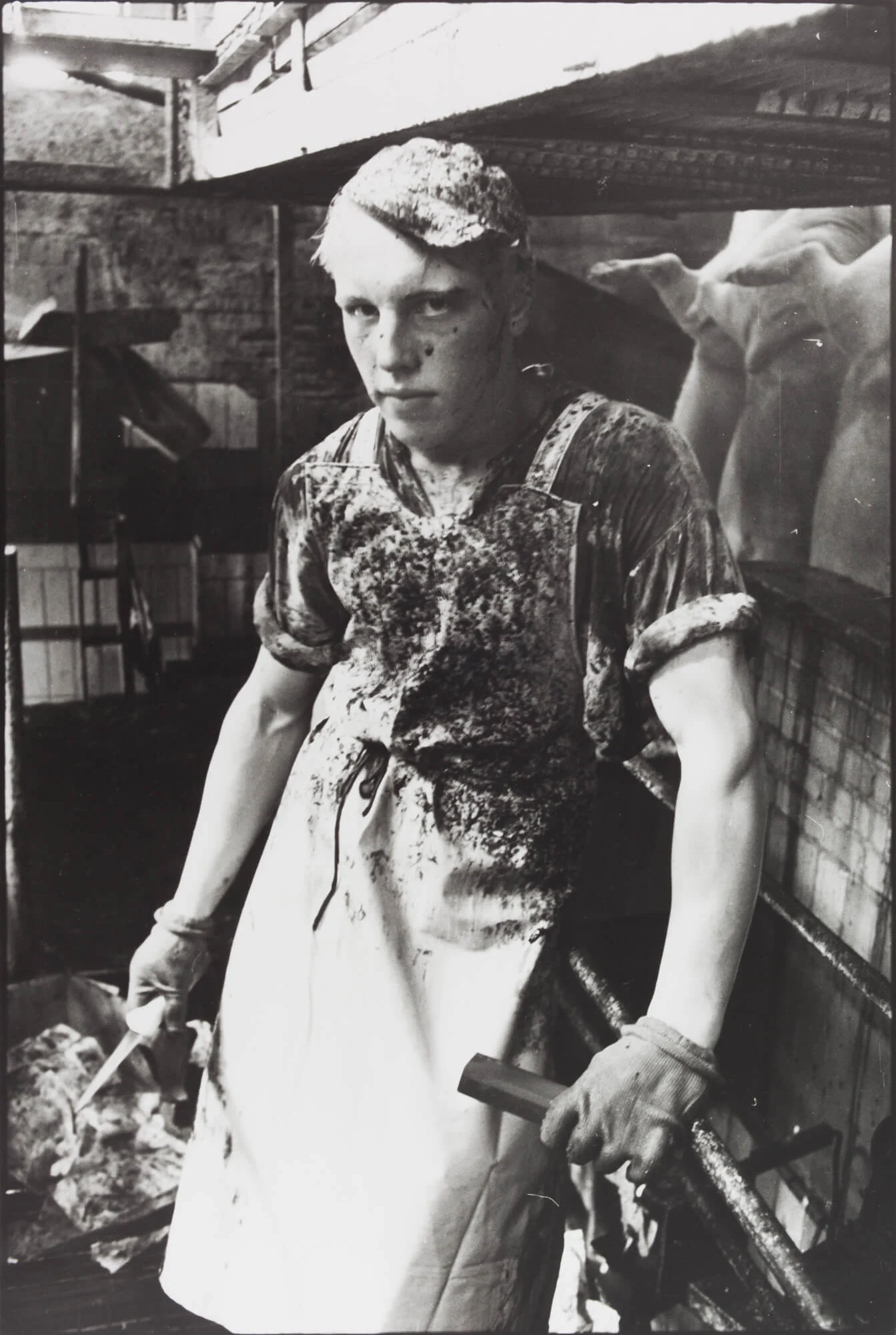

Then there’s York der Knoefel, a self-taught photographer from Berlin who built a maze out of steel plates, on which he had mounted photographs taken inside a state-run slaughterhouse in East Berlin. The work seems to draw parallels between the citizens of East Germany and the animals led to their death in VEB Fleischkombinat.

Rudolf Schäfer, meanwhile, gained access to the morgue of East Berlin’s Charité Hospital, where he shot carefully-framed and exquisitely lit portraits of the recently deceased. “I love how, even in death, the portraits reveal the singularity of each person,” Voss says.

Regarding the first time he gained the courage to take out his camera at the morgue, Schäfer recalls: “That day in the Charité Hospital where I stood in front of the corpse of a man for the first time in my life, I forgot everything I had wanted to do. My impulse was to run away. But the faces of all the corpses kept me there and that is how I made this work.”

The photos pack a punch. They’re not meant to be objects of beauty. “They are simply— in the narrowest sense of the term —consistent in their approach to the subject,” he continues. “Pictures of the victims of an earthquake, a terrorist attack, a drug overdose, or a traffic accident are pictures that we always look at thinking: ‘I hope that doesn’t ever happen to me.’ My pictures are consistent in their approach to the subject, because they do not give viewers any chance of absenting themselves from them.”

The artwork created by these dissident pioneers remains startling and pressingly relevant, as demonstrated by their reaction and ongoing influence. After the Arles exhibition, Voss was due to exhibit the work at Jimei x Arles, an official partner festival in the Chinese city of Xiamen. A few short weeks before the festival launched, Voss announced on social media that the Chinese state had censored her exhibition.

“The decision of the Chinese authorities sadly echoes the censorship which many of the artists presented in this exhibition experienced in GDR times," Voss said in response to the news. "But it is also an occasion for us to admire, once again, the destabilising and provocative power which continues to radiate from these works, so full of passion and liberty, more than 30 years after they were created.”

The use of the body as a political tool, a canvas upon which acts of protest can be exhibited, are now widespread in the protest movements of today: Extinction Rebellion, Black Lives Matter or #MeToo. In countries such as China, Russia and Turkey, where state-repression of artistic expression and the free press is de rigueur, traditional photojournalism and documentary reportage has ceded to a more relational and performative style of protest art, often with an explicit and unflinching focus on sexuality, gender expectations and the body politic.

The artists of the GDR are the brothers and sisters of the artists wrestling with the same questions in the here and now, using the same strategies, and continuing to redefine ideas of identity, representation and protest under comparably brutal and controlling regimes.