When a power cut and a computer malfunction caused Yemeni photographer Arif Al Nomay to lose years of work, he anxiously hunted for anything that might still be there. To his surprise, a set of photos taken at a Summer Festival in his country’s capital had survived, but they had been altered, their colors skewed and the details hard to distinguish. Since the festival took place the year before Yemen descended into war, the series would become a symbol for the pieces of everyday life that were lost as a result.

In 2014 Arif Al Nomay traveled with his camera to a park called The Seventy in Sanaa, the capital city of his home country of Yemen. He had been hired to take photographs at an annual festival, a celebration of the heritage that characterizes many of the country’s different regions.

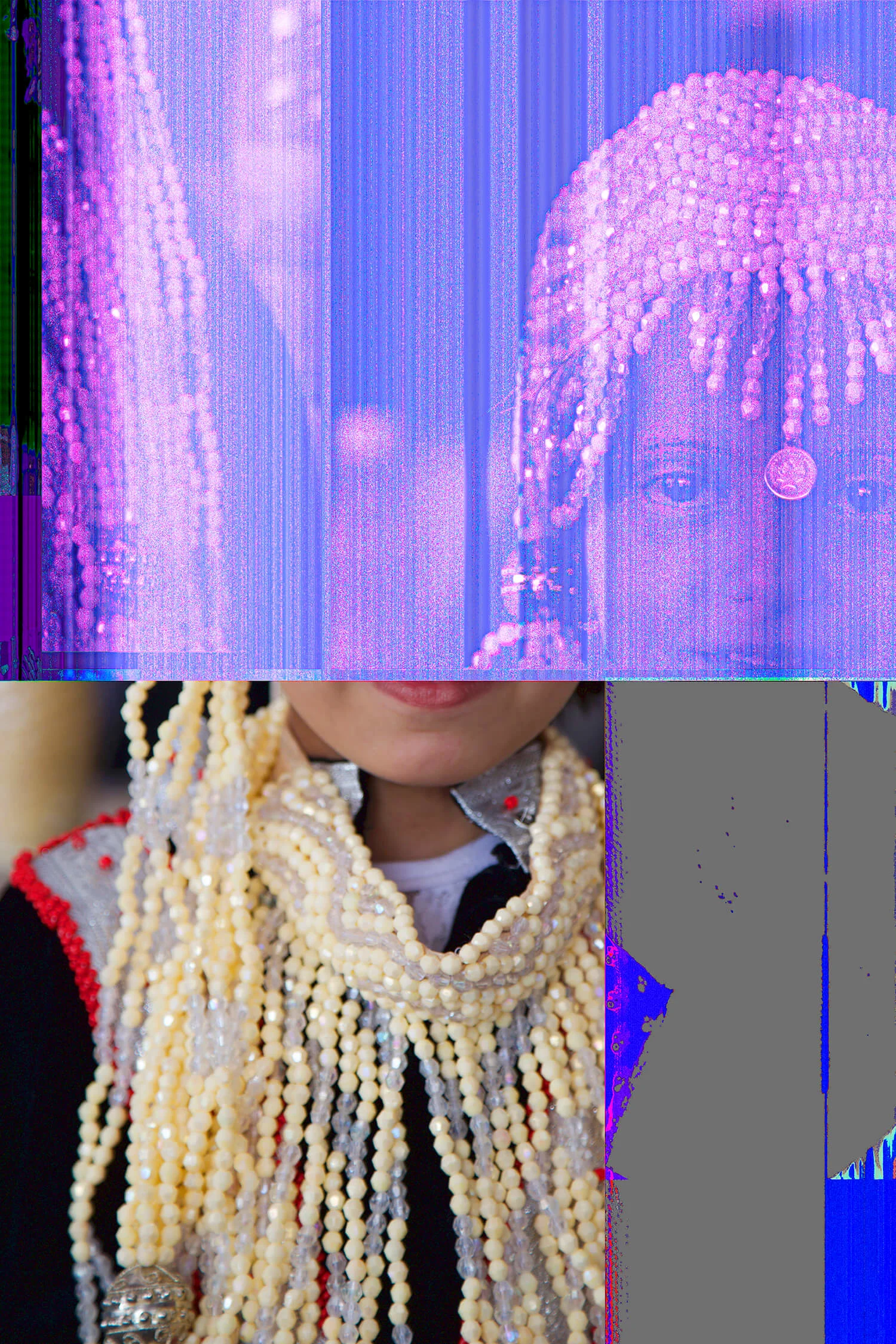

Soon after that day, a power failure caused a malfunction in his computer’s operating system, and the photo files were corrupted. What was left was a selection of glitch-ridden pictures, with the jubilant scenes from the festival covered and distorted by blocks of color and stray pixels. The following year, civil conflict erupted across Yemen, and Arif’s series would subsequently become a symbol for what had been lost with the outbreak of war.

“Sanaa’s summer festival included every kind of cultural activity you can imagine,” Arif says. “Folkloric dances, traditional songs, puppet theaters… even showjumping for camels!” It’s hard to see exactly what’s going on in his photographs, but if you look closely you can just make out a few things. Bunting hangs between buildings beneath a backdrop of blue skies; Children smile in traditional dress; musicians play their impressively-decorated instruments and inflatable cartoon characters tower over the whole scene. “No one can deny the happiness on the faces of the people who were there,” Arif recalls.

It was like any other day for Arif, as he’s spent much of his life behind the camera. At 19, he obtained his first passport and went to work in Saudi Arabia where his grandfather ran the Abha Photo Lab. “It was there, under my grandfather’s tutelage, that I learned about photography, analogue printing and coloring,” he says. “The sound of the camera shutter and the way the images would slowly appear in our dark room were like magic to me.”

Photos had already played a major part in his childhood. Arif’s dad was working in Saudi Arabia and would send money back to support his family and could only write letters or record cassettes to communicate with them. “I remember the first photo of me, taken with a Kodak instant camera,” he says. “It was sent to my father. He saw a photo of me before he saw the real me.” Arif now lives in Riyadh, the Saudi capital, and follows in his father’s footsteps by supporting his own family back in Yemen.

War is never the solution. I hope we can restore peace.

The corruption of Arif’s files was hard for him to take, as he lost years of work in the process, but it also sent his photography in a new direction. Serendipity had taken what was a simple documentation of a summer festival and turned it into an eerie and poignant reflection on the trials and tribulations faced by his country; the joys and intricacies of normal life overshadowed and overwhelmed by chaos. “I linked the matter to what Yemen is going through,” he says.

“I realized that photography can convey a message to the world without the need for literal translation,” he says. “I realized what we see is something we all have in common and photography could be the key to overcoming the barrier of language.” Since the festival his work has been geared towards exploring the cultural and political narratives of Yemen against a backdrop of regional conflict and transformation. “Series such as these can create a space for discussion and can act as a symbolic indication of memory, events and the faces of conflict.”

Arif says that many different interests and ideologies still struggle for domination across the country. “But war is never the solution. I hope we can recover and restore peace.” It’s a country often only spoken about now with regard to its unrest, and he speaks passionately about the side to Yemen which he feels is overlooked: how the Yemenis represent the era of the great and ancient civilization, and about how its capital Sanaa is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world. “We deserve to be respected and seen from a civilizational perspective,” he says. “I just want the world to know about us.”