Born and raised in Pakistan, Areesha Khalid has always felt that South Asian architecture is underrepresented. Her project, Diaspora Digest, is a fictional magazine celebrating that architecture, and is a visual embodiment of Khalid’s pride in her South Asian identity and heritage. She tells writer Dalia Al-Dujaili how the project is inspired by memory and romanticism and how she’s always been fascinated by the built environment's capacity to tell stories, as she walks us through five of her favorite designs.

“I was actually set to study medicine, a somewhat predestined family path, as is the case with most brown families,” begins artist Areesha Khalid, “[but] I quit medicine and started my bachelors in Architecture at the University of Westminster that same year.” Khalid, born in Rawalpindi, Pakistan and raised there until age 11, is fascinated by the built environment's capacity to tell stories imbued with diasporic nostalgia. She runs “Architecturbyari,” a blog where she creates and sells “South Asian spatial nostalgia art” as prints and showcases Diaspora Digest, a project catering to the global South Asian diaspora which began in 2020 and became a self-published coffee-table book.

After not feeling related to the structures and practices she was studying at University, she developed a gripe with the underrepresentation of South Asian architectural styles, and thus, “Diaspora Digest” was born. It began as a visual embodiment of Khalid’s pride in her South Asian identity and heritage, which wasn’t always the case growing up in Suffolk, rural England. A celebration, in other words, of growing into herself. “It was a way to navigate through my feelings of acceptance for my culture, which is expressed in my romanticized, nostalgic depictions of ‘home’,” she explains.

“I believe the spaces that we occupy tend to soak in the culture of the people that they house,” Khalid says on her interest in depicting architecturally concerned visual art. The artist believes spaces can tell people’s stories through color, pattern, writing, signage, wear and tear and much more. “Capturing this ‘lived in’ quality of space is essentially what conveys the culture and heritage in my work,” she explains. The spaces are further imbued with a glamorized South Asian architectural sensibility by taking cues from Bollywood movies by the likes of Sanjay Leela Bhansali, a favorite of the artist’s.

I believe the spaces we occupy tend to soak in the culture of the people that they house.

Spaces indeed tell stories, and it is a story that sits at the heart of all Khalid’s pieces, and it is a memory which catalyses the creative process, as the artist forms her entire imaged scene around a remembered object through a process of moodboards, photoshop, digital drawing, Rhino 3D, and procreate. Her pieces are informed by either her own experiences back home or a local’s story, since she is preoccupied with the creative capabilities of a ‘fond memory’ which she says will often be embedded in a space that the storyteller is able to vividly recall.

Usually a problematic artistic trope, this romanticization is self-aware, so instead of appearing adjacent to an Orientalist romantic depiction of South Asia, Khalid’s work becomes a sincere self-exploration of the diasporic conundrum, and the acceptance of the separation between herself and her homeland.

Autumn / خزاں / Khizan

One of the first digital collage style drawings Khalid made as part of the project, this piece is based entirely on a conversation the artist had with her mum. “I remember it was the beginning of Autumn here in England and the color palette of the streets was slowly shifting to deep oranges, crimsons and browns, and it was raining of course. Mum was recalling how she’d love to sit under the autumn sun outside with an entire carton of oranges to herself and peel and eat away while soaking the warm sun as the slight cool breeze passes.” When Khalid showed her mum the final image, she told her daughter that she felt so much nostalgia through the drawing, that “it almost felt like a romanticized painting of the memory in her mind.”

Grandma’s rooftop / چھت / Nani ke ghar ki chatt

“This image depicts ‘nani’s chatt’ or ‘grandmother’s rooftop’,” Khalid explains, “pretty much the only home I visit since I was a child is my grandmother's.”

Khalid chose to set this scene on the rooftop because of how much time is spent outdoors or semi-outdoors in social spaces in South Asian homes; the chatt (roof), the balconies, the sehan or aangan (courtyard) etc. “Even the smallest village homes will somehow appropriate such spaces,” she says. “If the weather is good,” she reminisces, “we often have family Eid barbecues and gatherings on the rooftop, or just unwind as a family on a ‘charpai’ (traditional hand woven bed) at night enjoying the cool summer night’s breeze with music, chai and snacks. Nani’s rooftop sits at the center of many cousin hangouts and family events, it's such a humble space but sees so much love and joy.”

Androon City

This is a significant piece for Areesha as it marked her 11th year in the UK; “I had spent exactly half my life (11 years) in Pakistan and half (11 years) in England.”

The artist sat down to draw a very traditional, old, androon Rawalpindi residential building, her birthplace, to mark this occasion. “But I unintentionally ended up with somewhat of an Asian/European fusion. It somehow dreamily represents past recollections of the city I was born in.”

A “RIBA” article commended this work for having an “almost child-like understanding of memory,” Khalid tells me, which she says wasn't intentional. “Perhaps my memories of the place I was trying to depict were all perceived from a child’s point of view… I haven’t been able to shake off this child-like, almost cartoonish style which I’ve actually grown to love!”

A winter evening in the hills

Portraying a winter evening in the hills of Murree, a mountain city in Punjab, Pakistan, this piece recalls a time when Murree had a different atmosphere. “In recent years it’s become crowded with tourists (specifically groups of men traveling on ‘boys trips’) from across the country wanting to experience a change of scenery and weather,” says Khalid, “I grew up visiting and walking the streets of Murree freely with my mum and siblings from a very young age, since my dad would often have to go there for work. We’d go with him and just enjoy walking the stretch of ‘mall road,’ a long street lined with shops and street vendors selling everything from hot snacks to traditional arts and crafts of the local mountain people.”

But during Khalid’s recent visit, she felt uncomfortable walking the same road, “getting cat called more times than I can count,” she unfortunately recounts, “by the rows of men lining up either side of the street. The Murree I remembered for its fun amalgamation of traditional haveli facades, dotted among British style pitched roof structures, the food, the people, the local culture. It had all transformed to a place I sadly no longer felt welcome or safe in.” Speaking to other women, Khalid has now gathered that this is apparently a huge and growing problem in the mountain city.

She counteracted this dilemma by populating the drawing with 99% women in response to her experience. A radical and empowering imagination led to a drawing of a women’s mountain city, “a safe space.”

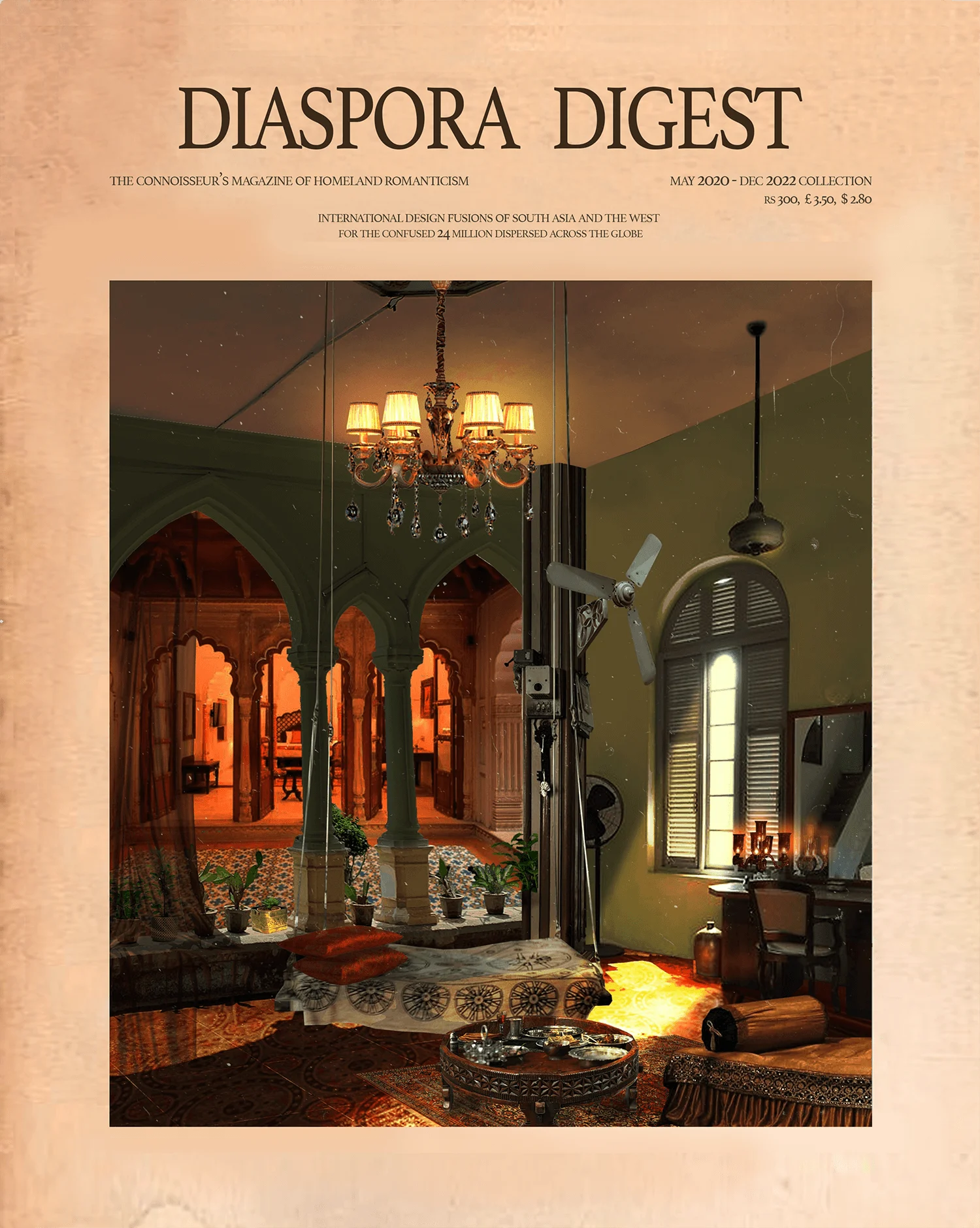

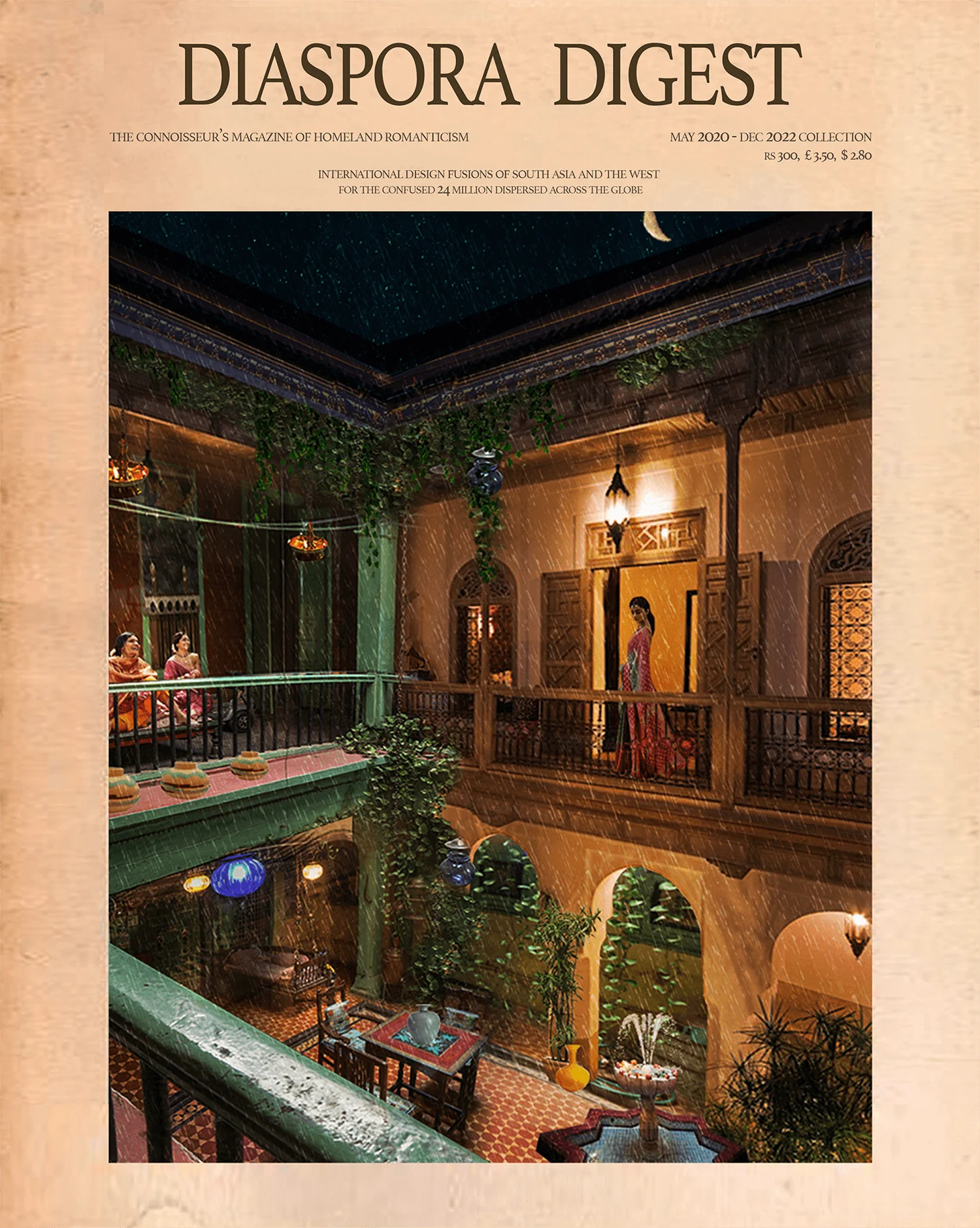

A 1950s evening at a typical haveli on the subcontinent

BBC’s “A Suitable Boy” and its 50s post-partition Architecture and interior design aesthetics left an impression on Khalid. Taking cues from the show—an adaptation of Vikram Seth’s seminal 1993 novel—Khalid made this digital collage of many different building elements combined to form a traditional 1950s home.

“The storyline of the show subtly interlaces the impacts of partition. I couldn't help but think of all the vibrant lives in such beautiful homes getting completely disrupted and displaced by partition and the homes becoming collateral damage left behind for reoccupation or abandonment,” Khalid says of the reference. She felt drawn to depict one of these homes in its “full traditional glory but with an underlying tone of melancholy and longing.” She tried to convey this atmosphere through a darker color palette which is still warm but “dull,” the rainy climate, and the nearly empty haveli (a traditional South Asian townhouse or manor house).