In 1989, the year photographer Antal Bánhegyesy was born, a violent revolution ended communist rule in Romania. Up to that point, the authorities had pushed an aggressive atheism as part of their agenda, but once they were swept away, something curious happened.

Ornate, gilded and steepled Orthodox churches began cropping up up everywhere, from rural villages to city centers. The Romanian people, it seemed, wanted their religion back.

Since then, more than 7,000 churches have been built and another 1,000 are currently under construction. Growing up in Cluj-Napoca, a city in northwestern Romania, Antal watched this happen. “During those years, it seemed like every other day an Orthodox church was inaugurated,” he says.

Antal was fascinated by what he saw and what it meant. He balances an insider and an outsider point of view – his family is Hungarian – and while studying photography in Budapest, he decided to document the churches in his series Orthodoxia.

Shot straight on or from a slight low angle, the churches in Antal’s images dominate their surroundings. In one photo, shot from atop a nearby mountain, a decorative white church stands in stark contrast to the bland blocks of brown buildings around it. The colors of the churches’ facades are usually subdued, but inside it's a different story. In one photograph, a priest is made tiny by the resplendent yellow-gold reredos behind him.

Antal has traveled back to Romania eight times, covering more than 10,000 km and visiting 200 churches. But few tell the story of Romania's new religious fervour better than the church he found in Ungheni, a city almost bang in the center of the country. Here, the Orthodox church bought the land where a Greek Catholic church had been built in the 18th Century. Instead of demolishing the original building, it was agreed the new church would integrate with the old.

In Antal’s image, the modest Catholic church is dwarfed by the voluminous chamber of the newer structure that engulfs it. The bizarre image of a church within a church has become a powerful visual metaphor for Antal’s investigation into the dominance of the Orthodox church in post-socialist Romania.

“Officially there is religious freedom in Romania,” Antal says. “However the situation is much more complex than this.” There are 18 recognised religious orders in the country, but nearly 90% of state funding for church buildings goes to the Orthodox church.

During the communist period, many churches were destroyed by the atheist government. Now though, by choking off funding to other religious groups, a different sort of hegemony is emerging.

“Physical destruction has turned into a more invisible, slower and smoother capitalist demolition," Antal says. This desire to build a strong, single Romanian national identity reminds him of the Communist era – only the symbols have changed.

People are starting to protest the way this money is being used, but still the churches appear. In 2018, work began on the Romanian People’s Salvation Cathedral in Bucharest. Once finished, it will be the second tallest building in the country and the biggest Orthodox church in the world, with room for 5,000 worshippers.

“A huge amount of money – 110 million euros so far – has been invested in it,” Antal says, "Everyone knows that Romania is one of the poorest countries in Europe.”

Physical destruction has turned into a more invisible, slower and smoother capitalist demolition.

What’s more, with so many churches being built, many stand empty. There aren't enough worshippers to go round.

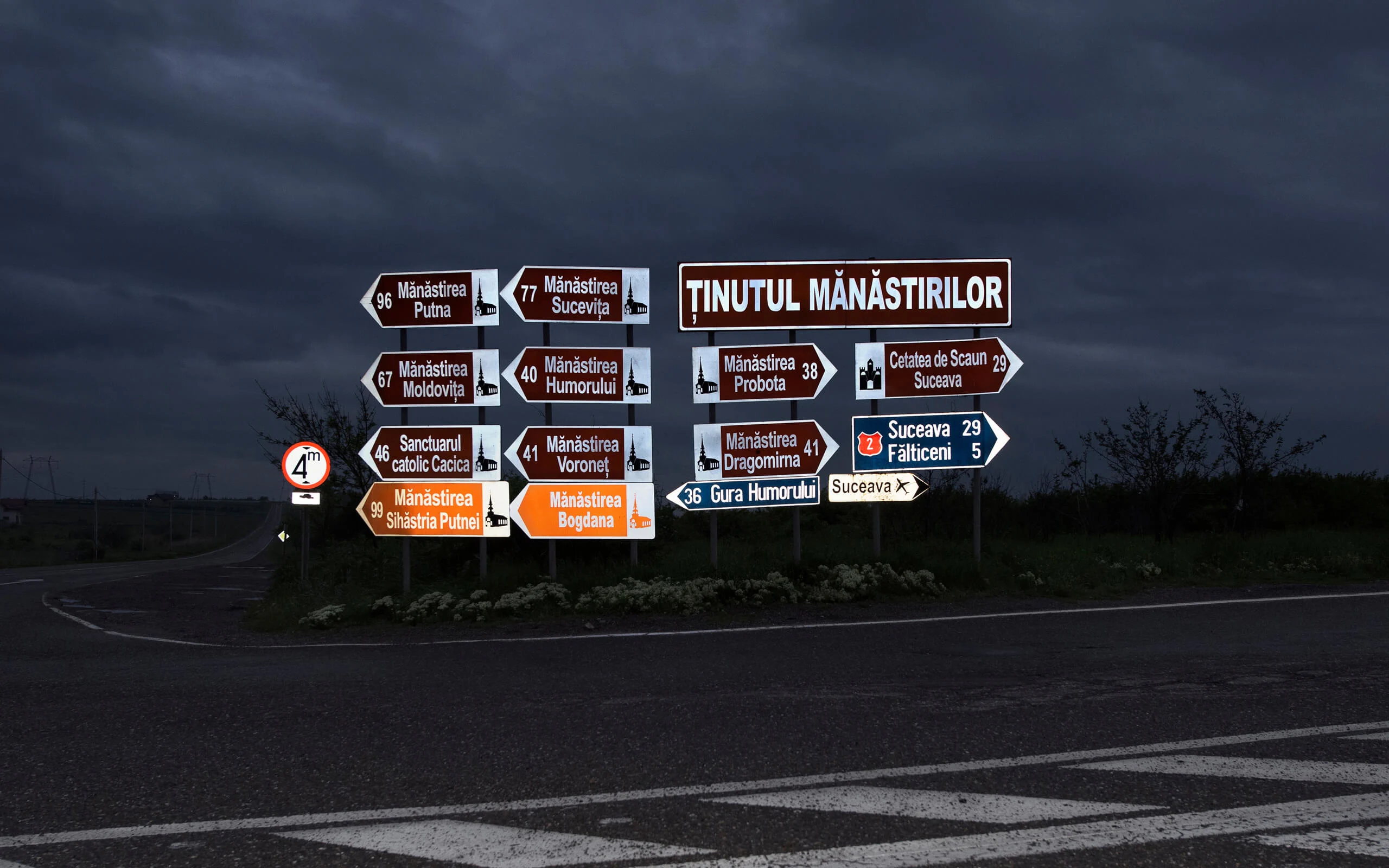

This is beautifully, ridiculously summed up in Antal's image of a roadside. Signposts for 11 different churches reflect back the light of his camera flash against a moody sky. It seems like it must have been photoshopped to create a digital collage, but no.

In Antal’s photos, it's not just the buildings that tell the story. Glimpses of men in rich black robes suggest the human efforts that are driving this phenomenon. “It's important to keep the balance between the environment and people’s presence,” he says, “and to search for new situations which present the complexity of the church constructions in both a symbolic and documentary way.”

On location one day, a priest came up to Antal after noticing he was taking photographs. “He started talking to me, meanwhile he was holding my hands very strongly,” he recalls. “Although he was kind, the squeeze seemed very aggressive. For me, this kind of encounter symbolizes the Romanian Orthodox church.”