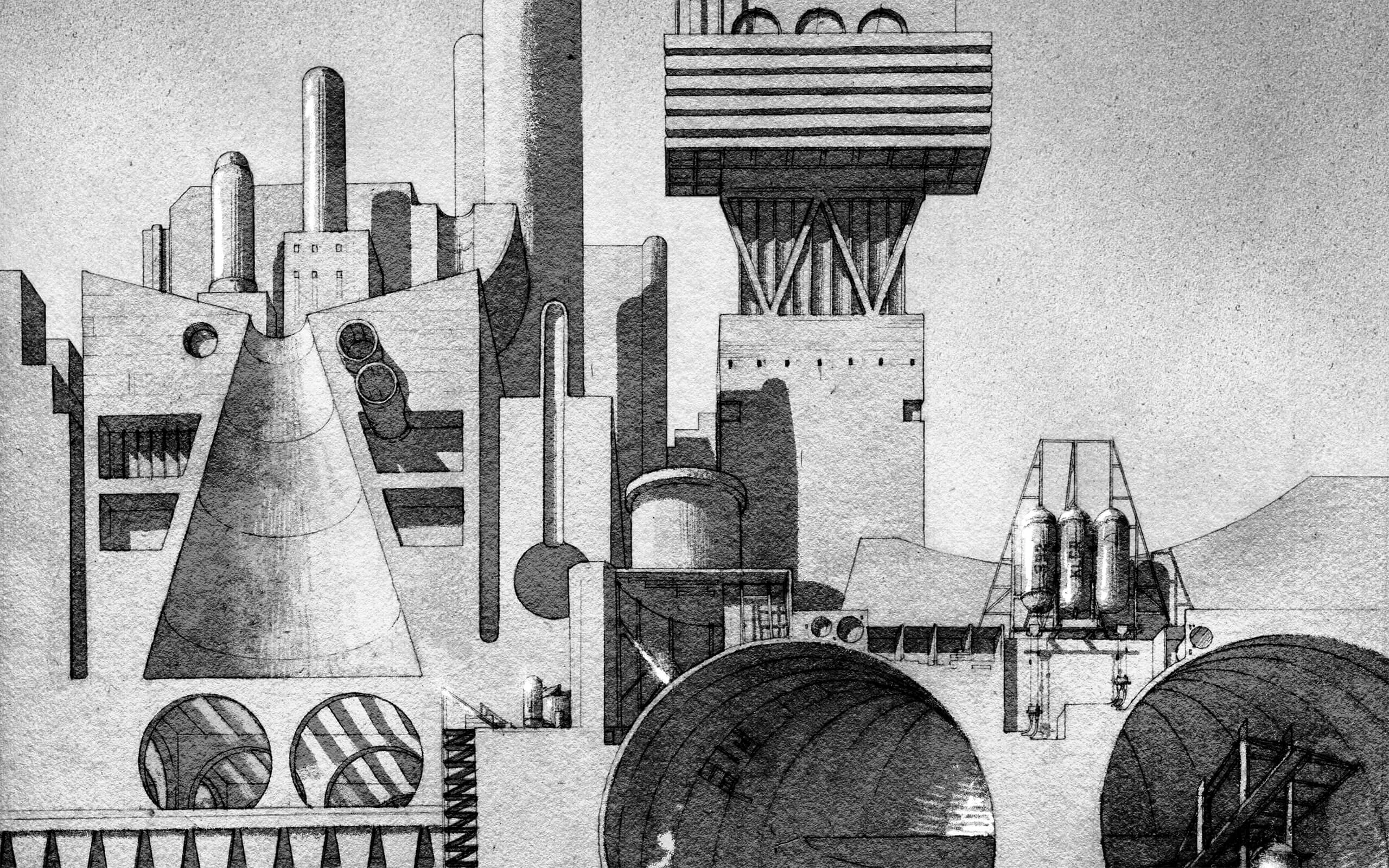

Illustrator Anna Mill grew up in the very rural countryside of Yorkshire, England. Living in a small village, she was always fascinated by cities, and wanted to get to the biggest city in the country as soon as possible. Giving into the lure of city life she went on to study at UCL, and found her calling in an architecture course that consisted of both architecture and fine art, that was deeply rooted in conceptual thinking and free, imaginative design. “It really expanded my understanding of what cities and buildings are, what they mean and how they work as the frame for human activities and the stories that might be going on inside them,” she says.

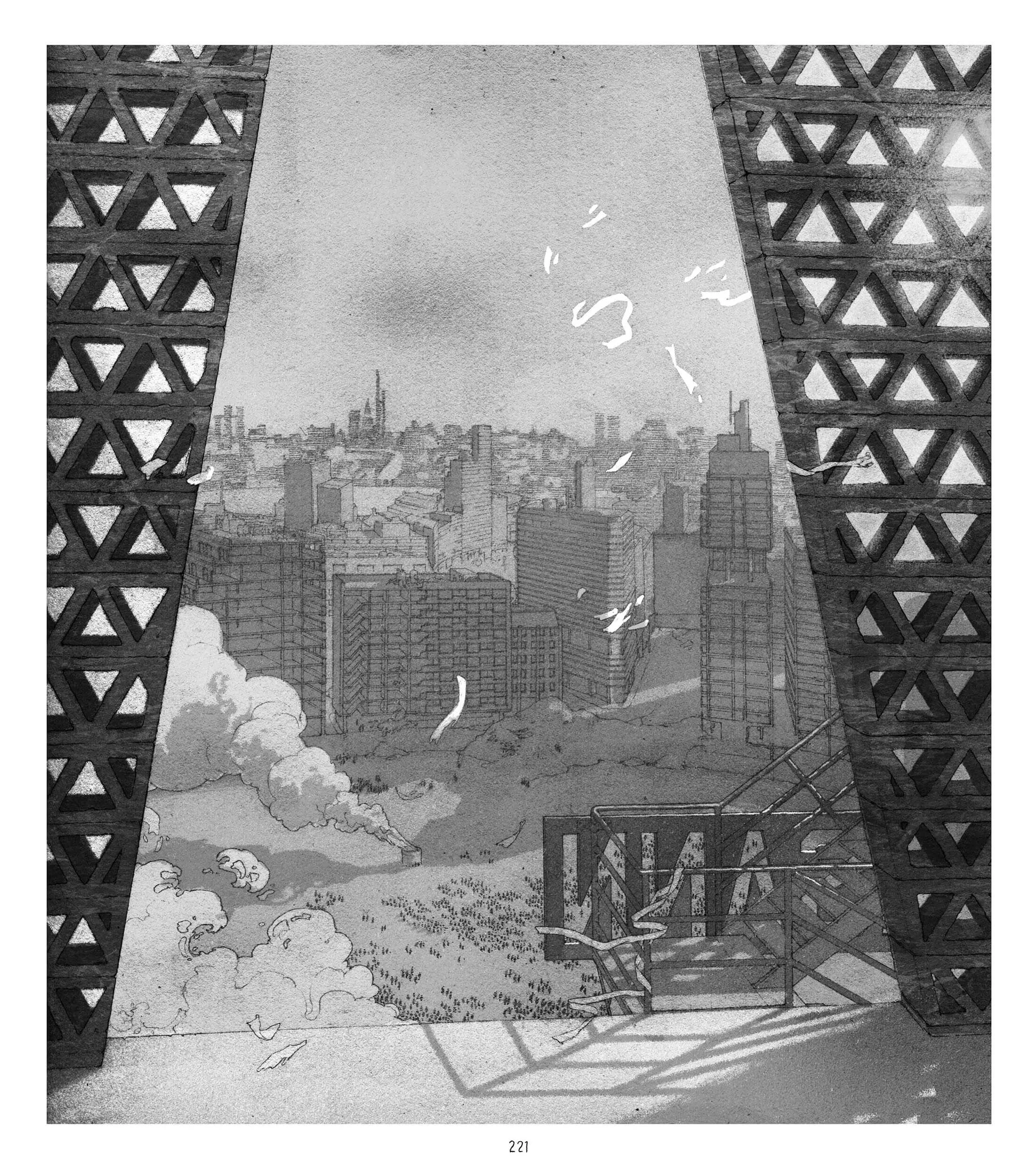

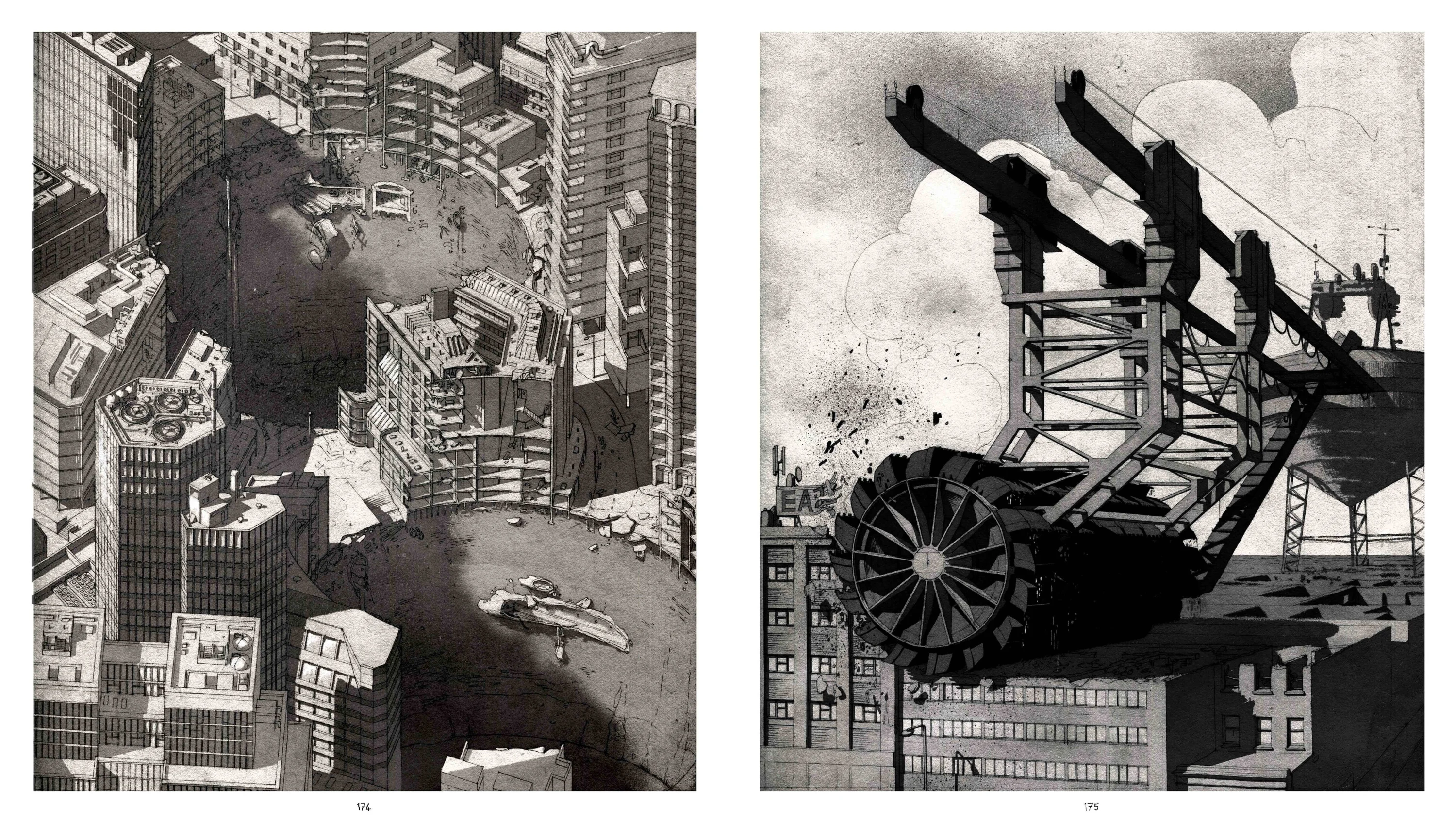

With this passion for buildings, cityscapes and stories at the forefront of her mind, Anna’s graphic novel Square Eyes saw her create not only a cityscape but an entire world, a futuristic, dystopian universe with a vastness that only reveals itself as you turn the pages, a journey into Anna’s creativity.

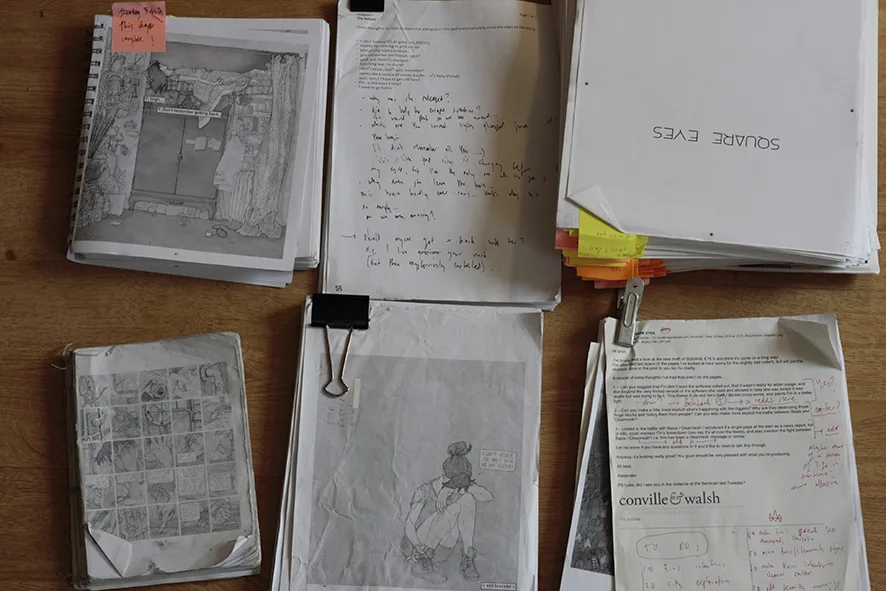

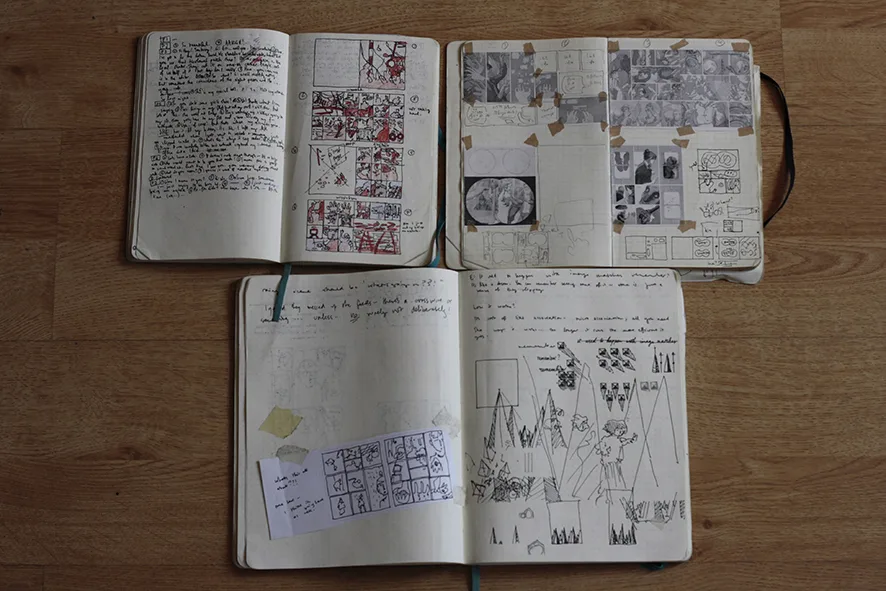

What eventually became an eight year labor of love began simply as a competition entry. Anna and fellow student Luke Jones entered a four page comic book into a graphic short story competition run by The Observer. “We were both intrigued by the comic book format because as architects you become obsessed with beautiful drawings,” Anna says. “What is the most complicated, detailed thing you can communicate through drawing? It’s like the extreme sport of drawing.”

The pair were slightly disappointed with the finished work, even though they came in second place, but despite this they were approached by a literary agent who had seen something special in them. He helped them put together a proposal for a full-length book, Anna doing the illustrations and Luke working with her on the story. And that was it; Anna left her architecture course and they fell down a graphic novel rabbit hole.

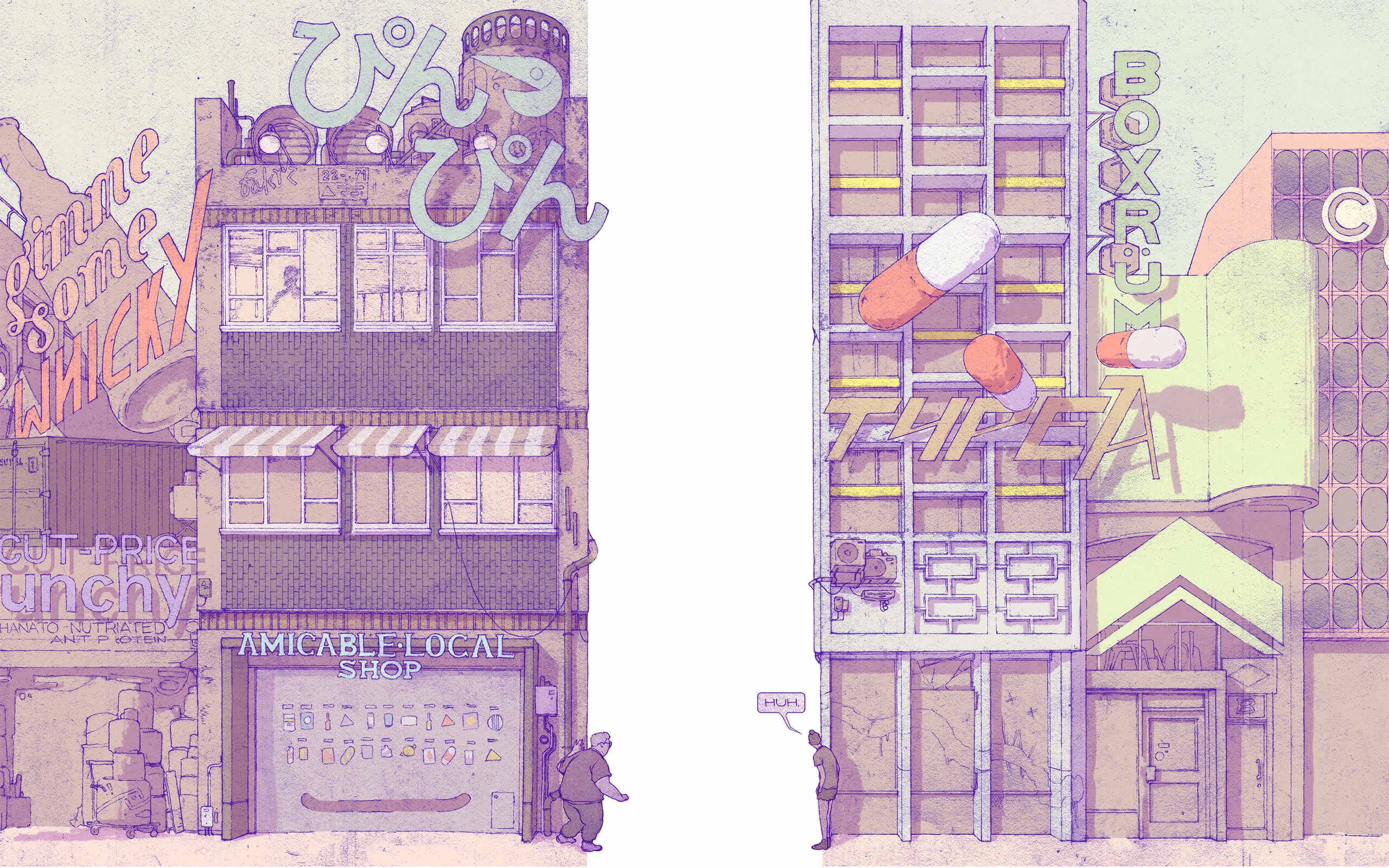

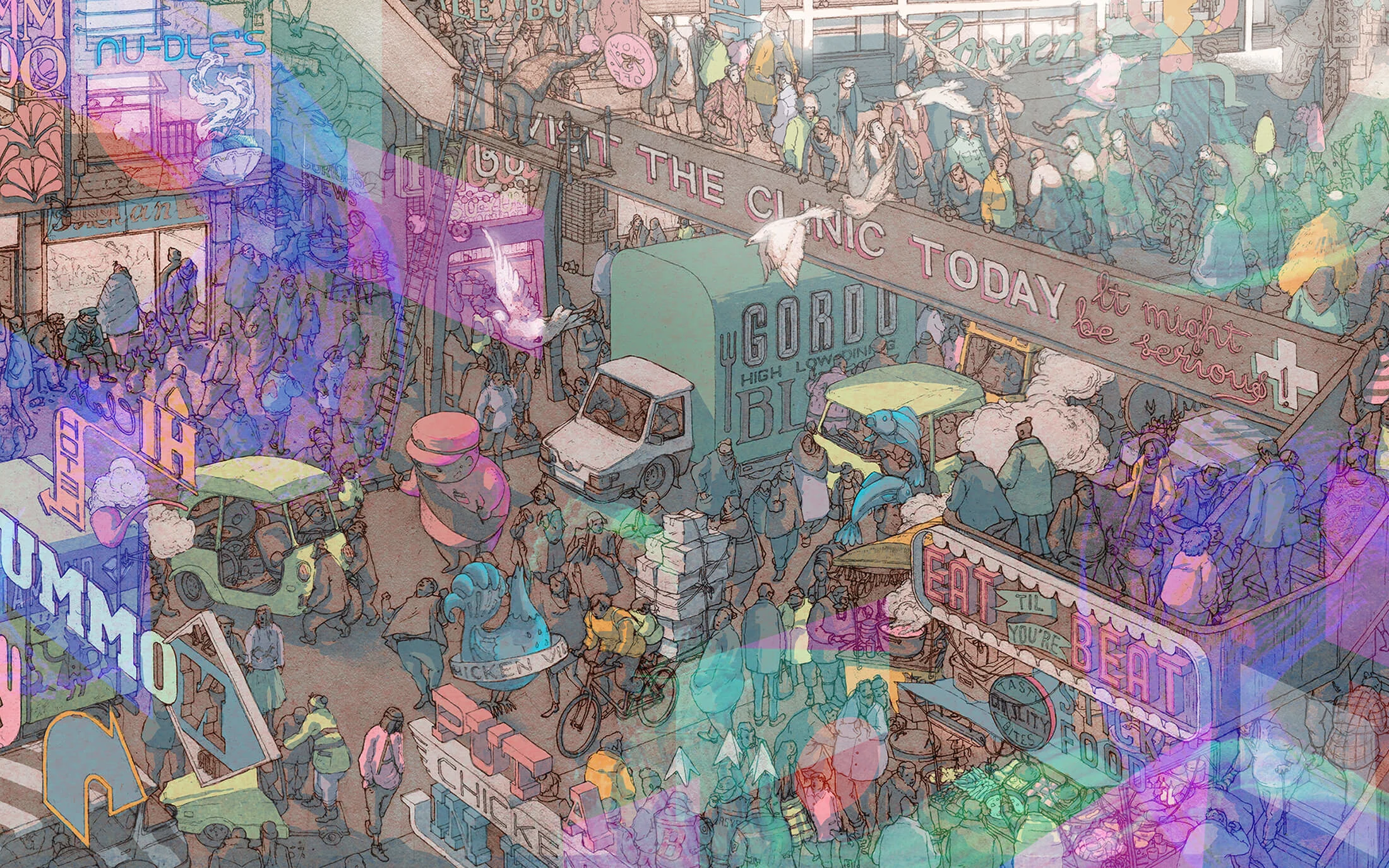

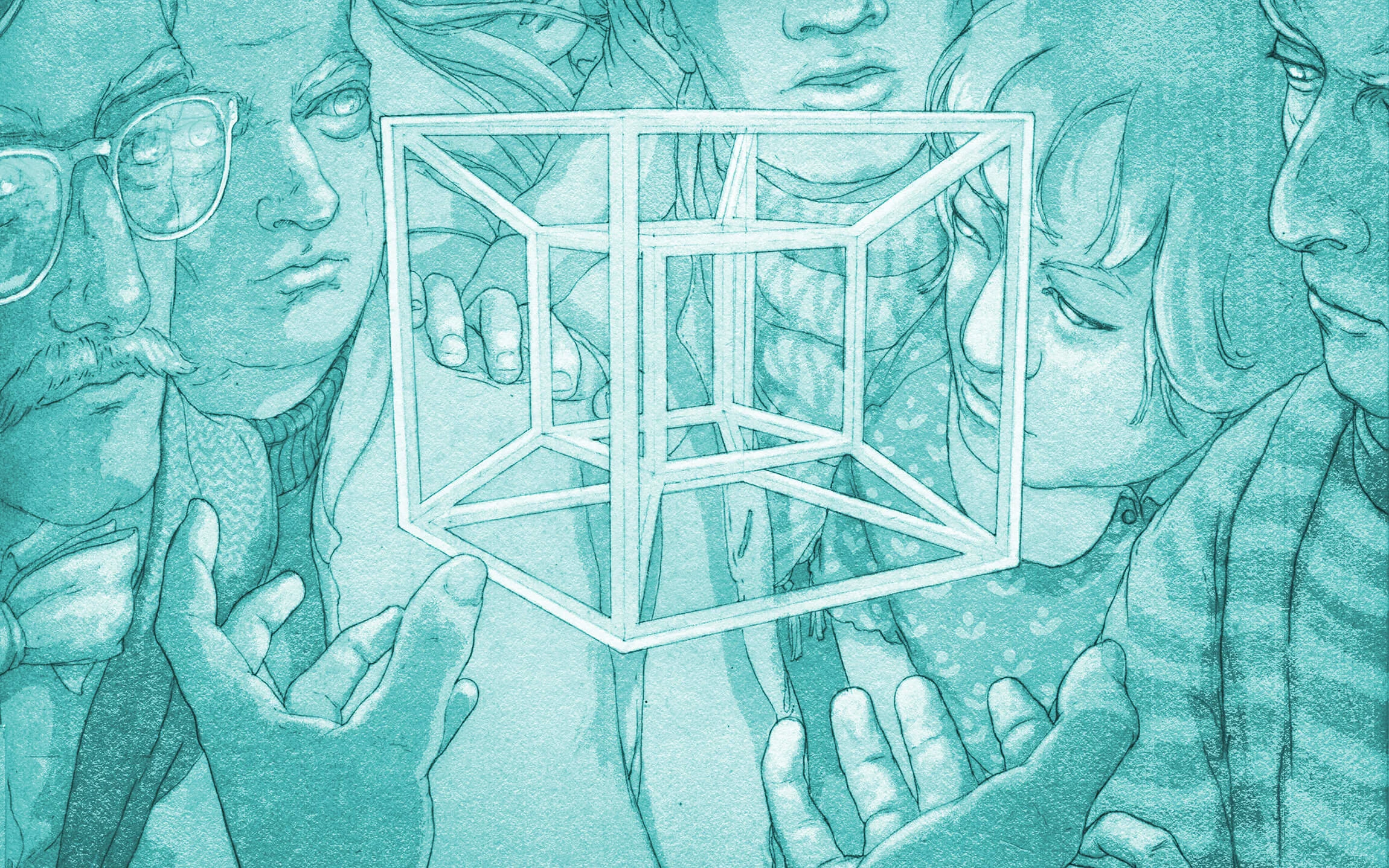

The story of Square Eyes follows female protagonist, Fin, and is based around the premise of augmented reality, a virtual reality in which the real, material world is enhanced by computer-generated visuals. “It’s this idea that you’ll be able to add digital layers onto the physical environment that then completely changes what things will look like,” Anna explains. It’s a concept that’s explored at length in the book, but one which is also on its way to becoming a reality in the future. “As an architect, you’re used to spending three years designing a building that will stand the test of time,” she says. “And then you’re confronted with this opportunity where you might be able to instantly change a building to look completely different, as many times as you want, with the press of a button. And do that to the entire environment!”

Anna also thought augmented reality would be interesting to explore visually, having “exciting and fantastical imagery juxtaposed with the banal material of the physical world that it’s set against.” According to her this is a concept that would worry many architects, but as someone with one foot in illustration, she was excited by the prospect of using an entire city as a canvas, being able to create whatever weird and wonderful ideas spring to mind.

It’s hard to create a story in this future setting and it not be a dystopia.

In the novel’s universe, augmented reality is gradually starting to take hold in society, and it’s being implemented in certain areas of the city before others. Anna and Luke liked the idea that people would want to move to areas where technology has been fully integrated with their surroundings. “What does that mean for the old bits of the city? The places that aren’t optimised with augmentation?” Anna says. To emphasise the differences between the two extremes, she and Luke decided that digital parts of the city would be shown in full color and the real physical material of the city would be shown in grayscale. “There’s times when the protagonist crosses a border into a part of the city that’s mostly offline, and she’s crossing between two worlds that look completely different,” Anna explains.

Anna likens this idea of the online and offline worlds to a person living in an area that has no WiFi or internet connectivity of any kind, assuming that they might be desperate to move to a more connected area. While this assumption might be based on her own childhood in a rural area, I wondered though, if a small percentage of the population might actively seek out the offline parts of the city. Just like the traditionalists that we see in our real world who haven’t come to accept technological advances that now govern our day to day, might there be people in Anna’s world desperate to return to the simpler days, to some blissful nowhere? This was something she and Luke considered, but which they didn’t have space to explore in the book.

It’s questions like this, though, that have led some reviewers of the book to claim that it “bottles the zeitgeist”, or presents a future that is “all too plausible”. “It’s hard to create a story in this future setting and it not be a dystopia,” Anna says. The augmented reality technology begins to cause problems, but Anna is keen to emphasise that this is because of the way it is being used by an evil, dictatorial company, rather than because of the technology itself. “We didn’t want to tell a story saying that technology is evil,” she says. “We wanted to say there are so many avenues and possibilities with it, but it’s when your access is limited, when it’s a tool that is controlling you rather than you rather than you controlling it, that’s when it becomes problematic.”

This is where the story again relates to the real world, to our own complicated relationships with technology. It seems all too common now for questions to arise around whether the speed at which technology is advancing is a good thing. Who is really doing the controlling? And while they might inspire her creativity, Anna doesn’t dwell too much on things that she can’t control. “All you can do really is spend eight years drawing about it and see where you end up!” she laughs.

Anna and Luke both admit to going through an incredible love affair with this story. “In the beginning, if someone had said it would take eight years, I never would have done it,” Anna says. “But it’s very important to be woefully ignorant of the magnitude of a task before you do it!”

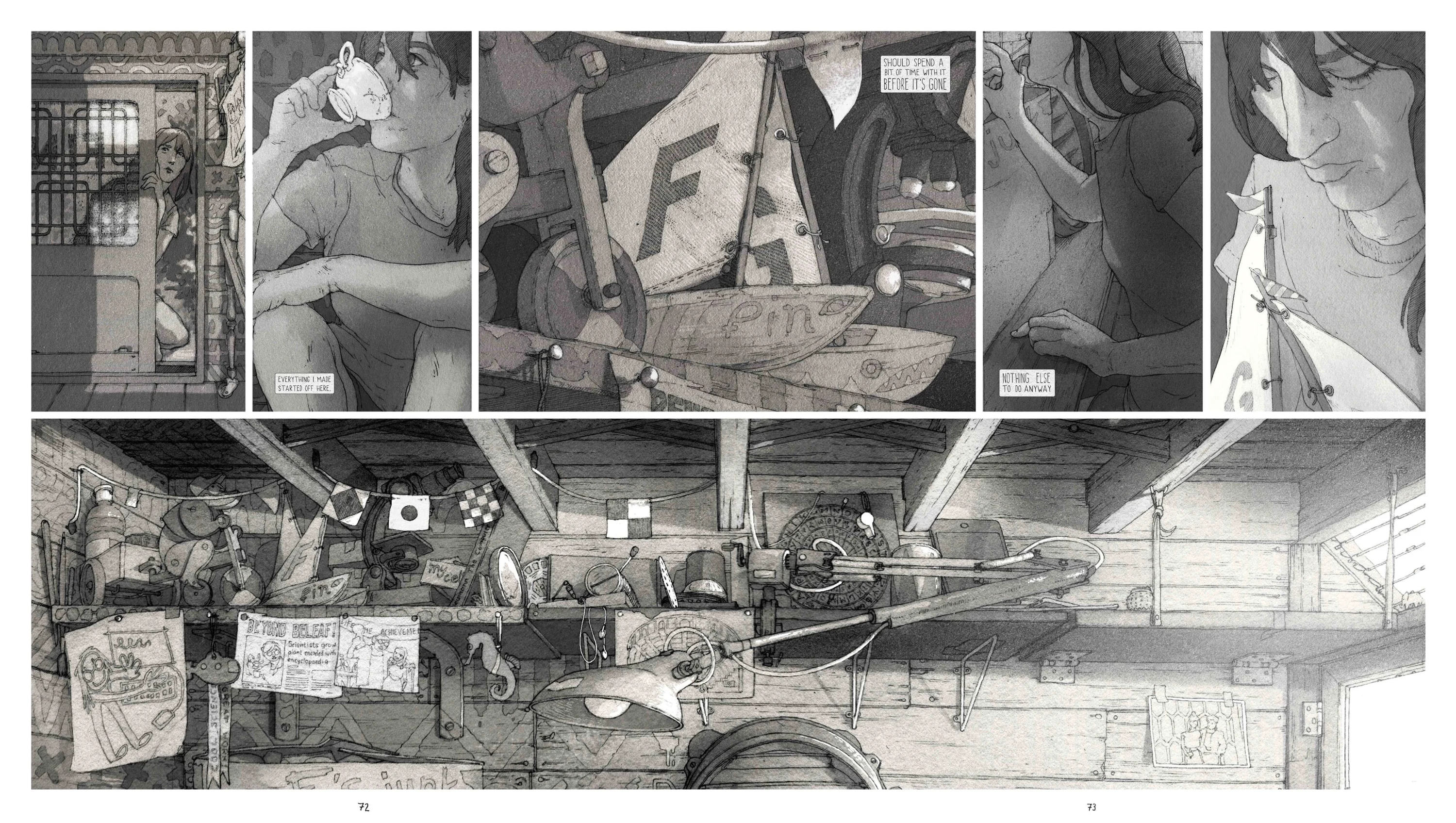

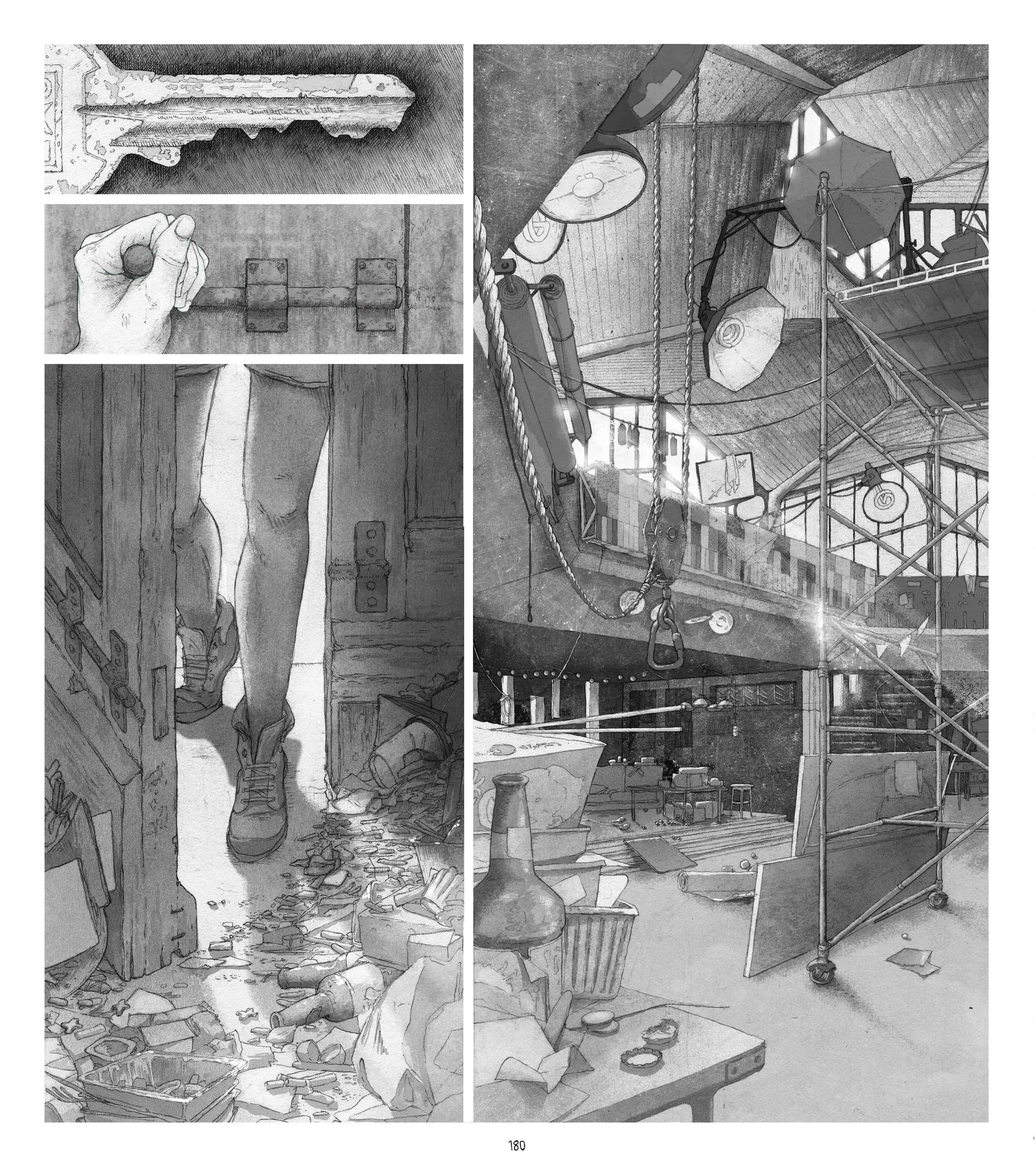

When it came to process Anna chose to create the entire novel by hand, using historic drafting techniques, an odd fact since the book’s subject matter is all about the future and digital technology. “I really feel like so many people are alienated by something being sci-fi, and by the trappings of something looking futuristic,” she says. “I wanted some of that material warmth in it, to create the feeling that it had been crafted by hand.”

There’s sequences where someone’s just wandering silently around a space.

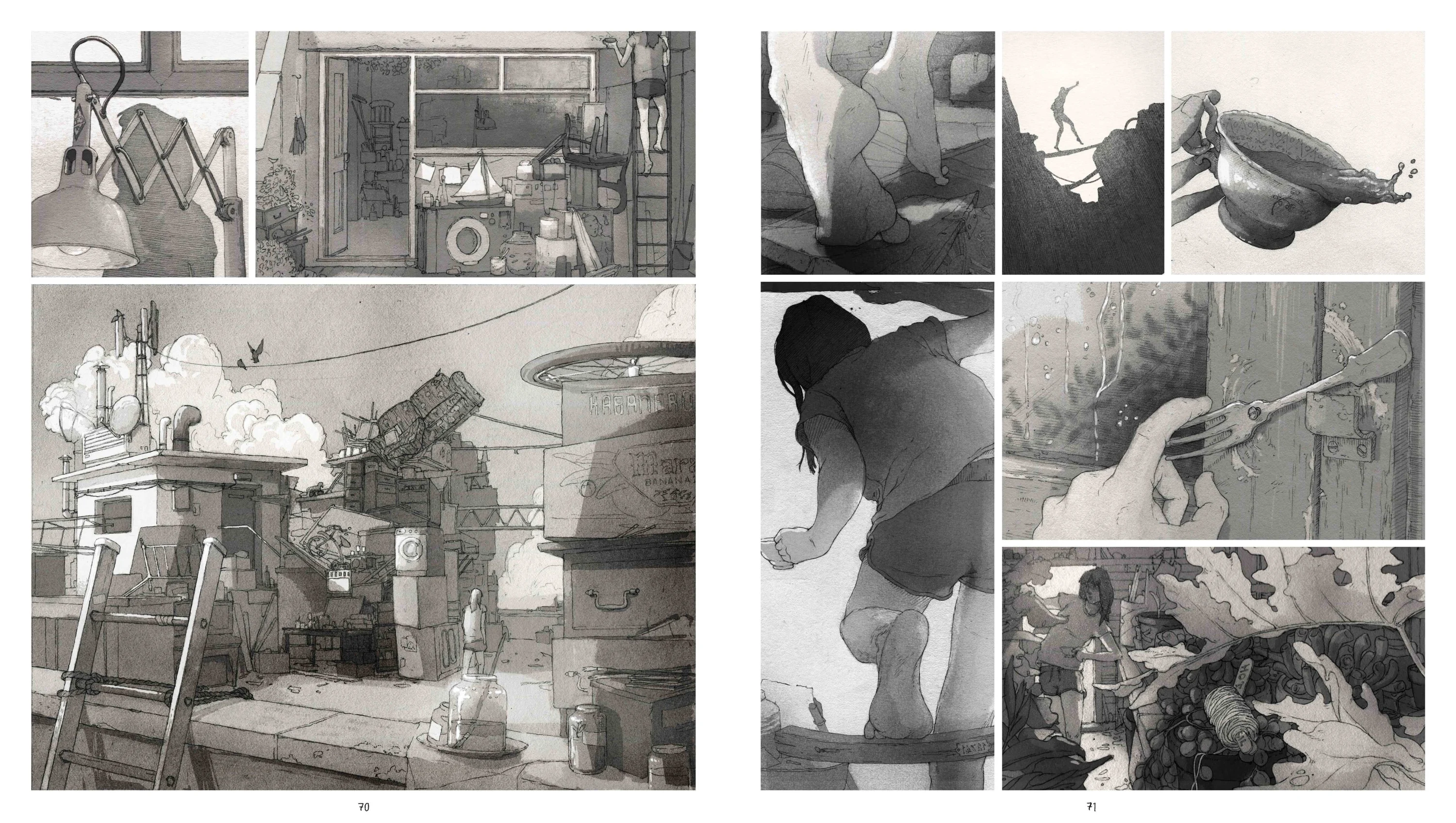

Anna’s experience in architecture invariably adds an extra layer to her creation of a whole new world. When she creates artist’s impressions for architects, they start with a big vision for something they want to propose, a zoomed out version, but once that is set she likes to dig in to all the little, intricate details and think about how people will actually live in the space. “I see it exactly the same, whether it’s a proposal that’s going to be built next year or a future city like Square Eyes,” she says. “I think it’s important that you get down to the level where you think about people’s teacups, and where they go on the shelf. What are the objects around them and where do they sit while they’re drinking that tea? If you’re not going right down to the minutiae of the everyday human detail in that setting, you don’t have this richness and you can’t bring it to life in the same way.”

Her time conceptualising real world building plans means the universe of the novel is incredibly detailed. It reveals itself before your eyes like a real life city, while Anna considers how each character would function in their home on some idle afternoon. She considers the way in which architecture influences how people live within it, and in turn the way people’s behaviour influences the architecture.

In the end, once you look past all of the storyboarding and thumbnails that had to be done, Square Eyes afforded Anna the opportunity to focus entirely on her love of drawing, and her love of creating new worlds. At the beginning of the project, all those years ago, she and Luke had ideas of settings they wanted to explore, but Anna started drawing them before they had even figured out where in the story they would go. “The first place I drew was a sort of 20th century church that was repurposed to be a start-up hub and then was abandoned again, and the other was the protagonist’s grandmother’s flat which she goes at the start of the book, a flat on a brutalist estate,” Anna says. “Because we hadn’t fully decided what would happen in the story, there’s a few of these sequences where there’s someone just wandering silently around a space.”

This is the true beauty of Square Eyes. It has a compelling and relevant story, but when you look past that, the visuals themselves are captivating even when you’re just flicking through it. On her eight year odyssey, Anna has created a novel in which characters from all walks of life roam through a mystifying world, often just quietly living and breathing in their surroundings.