Few outside of arts circles might know the name of the late Nam June Paik but in his native Korea, the original video artist is a household name. Filmmaker Amanda Kim has made her directorial debut with “Nam June Paik: Moon Is The Oldest TV”, a documentary that reveals how he was one of the important artists of the 20th century. Writer and editor Zing Tsjeng speaks to Kim to learn why she was compelled to spend a long and involved five years making the film and to understand how Paik’s work feels strangely prescient to what’s happening in tech and the world today.

As part of our ongoing partnership with International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA), we selected “Nam June Paik: Moon Is The Oldest TV” as our pick of the 2023 festival. The film will be screened at WePresent Night at Eye Filmmuseum on November 16, alongside a conversation with director Amanda Kim.

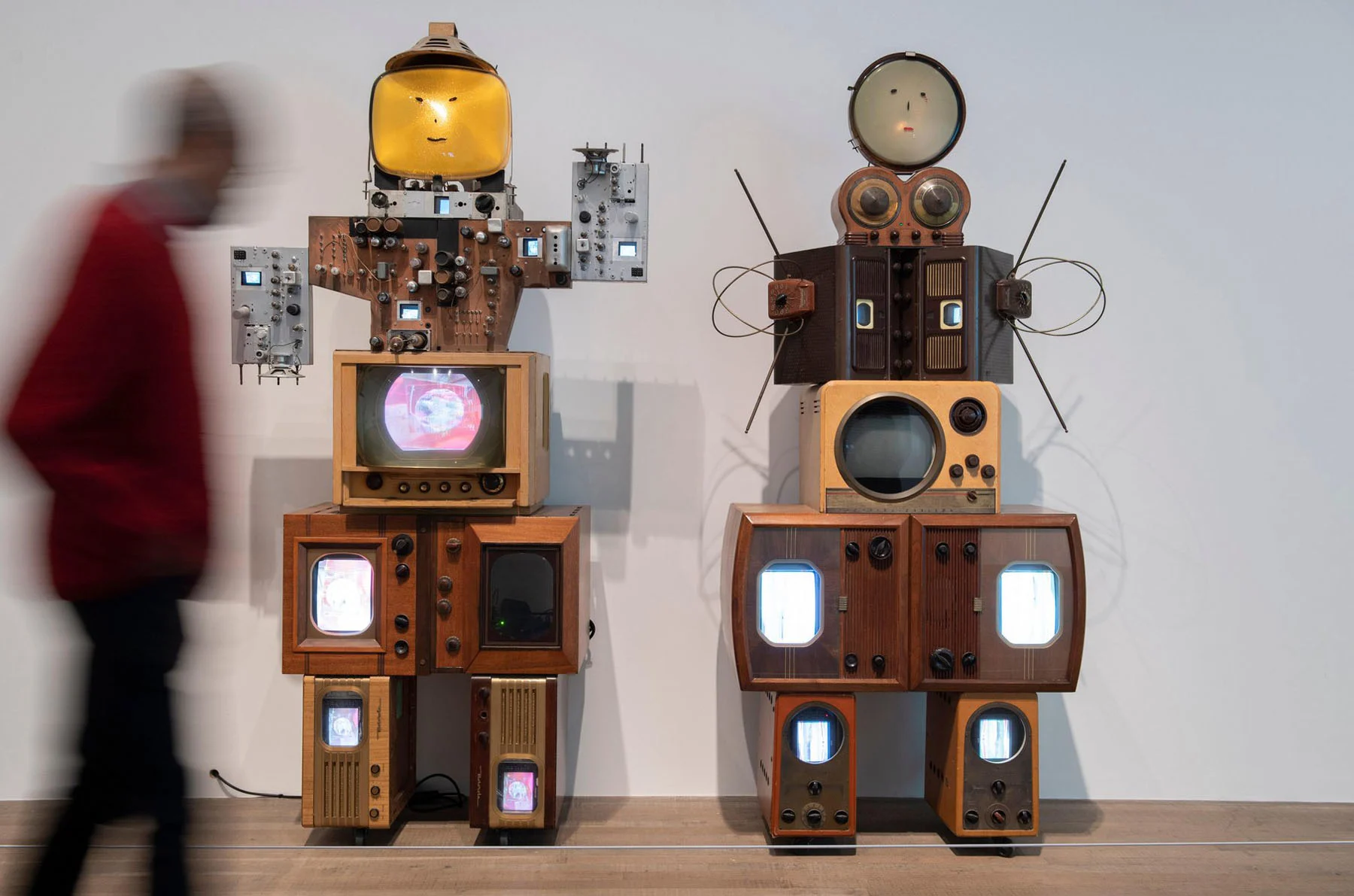

Nam June Paik has been called many things. Cultural terrorist. Global visionary. The man who coined the phrase “electronic superhighway”. But perhaps none more than his latter-day moniker: the father of video art. The Korean artist and pioneer was born in 1932 and died in 2006, the year that birthed both Facebook and Twitter. More than any other cultural critic or technologist, Paik predicted the world that we now live in. In 1974, he was prophesied a “broadband communication network” that would connect the world remotely; he also saw a future in which “everybody will have his own TV channel”. For the first few decades of his career in the US, however, Paik battled excoriating reviews, financial precarity, visa woes and even, at one point, faced arrest.

Though he described himself as a “poor man from a poor country”, Paik was born in Seoul into an affluent family. He studied abroad in West Germany and initially intended to become a composer, until an earth-shattering encounter with the avant-garde music of Arnold Schoenberg, Karlheinz Stockhausen and John Cage, who later became a close friend. Paik promptly ripped up his metaphorical sheet music and plunged into the world of performance art and the fringe artistic movements springing up across Europe and in New York. But success didn’t find him easily; he was dogged by controversy, not least thanks to his work with classical cellist Charlotte Moorman, who collaborated with him on works in which she performed topless—performances that violated public indecency laws and saw both of them get in trouble with the police.

Paik is the person who showed how it would be possible through the democratizing power of technology.

It wasn’t until his 40s—with the breakout work “TV Buddha” (1974) and others—that the world finally began to understand his vision. Featuring a stone Budda that Paik had lugged home for far too much money—as his wife, fellow artist Shigeko Kubota, remembered—gazing at a live image of itself on a television set, it encapsulates many of the themes that Paik returned to time and time again in his work: The use of screens; the relationship between medium and viewer; the humanizing effect of technology and, of course, Paik’s uncanny Nostradamus-like ability to divine the future. (It’s not so distant a leap from “TV Buddha” to us watching Kim Kardashian watch herself on her phone while taking a selfie.)

If Andy Warhol predicted that everyone will be famous for 15 minutes; Paik is the person who showed how it would be possible through the democratizing power of technology. Another landmark work, “Global Groove” (1973), cuts together footage of Pepsi commercials, Navajo singing, Allen Ginsberg, traditional Korean fan dancing and a psychedelically distorted Richard Nixon, among others. It resembles, if nothing else, like surfing TikTok Live at two in the morning. Paik, who had a gift for talking otherwise sober TV engineers and technicians into signing up for the Nam June Paik circus, somehow convinced the PBS network to broadcast this audacious work on public television. “Jam your TV stations! Now artists are striking back TV [sic]!” he declared in a press release announcing the show.

Amanda Kim’s dazzling film “Nam June Paik: Moon Is The Oldest TV” traces Paik’s life from his years as a rebellious young Marxist in Seoul to his final years as a wheelchair-bound godfather and mentor to a whole generation of video artists, continuing to make work up until his deathbed. And yet Paik—even after his devastating stroke—retained that impish sense of humor and irrepressibility, not least when he accidentally dropped his trousers and underwear and flashed then-US president Bill Clinton and former South Korean president Kim Dae-jung at a state dinner. As Paik puts it in Kim’s film: “I have a few more tricks to play before I die.”

“He’s punk!” Kim laughs over Zoom from Paris, where she is currently promoting the film. “He plays with your assumptions of him as an Asian person and as an artist. He always challenges what you might think of him and flips it upside down, like he does with the television or the piano.” Her documentary follows on from a critical reappraisal of his work in Europe, including a major retrospective at the Tate Modern in 2020. She sits down with Zing Tsjeng to discuss her film, Nam June Paik’s life and why the Korean visionary continues to inspire artists today.

Why Nam June Paik’s work matters today

Everyone thinks of him as a video artist, but I think of him as a thinker.

Amanda Kim: Everyone thinks of him as a video artist, but I think of him as a thinker. He crosses all mediums. He painted, he did performance art, he’s a musician, a sculptor, a video artist—all of the above. His unifying theme is about breaking taboos. At one point in the film, Mary Bauermeister, one of Nam June Paik’s best friends and a wonderful artist in her own right, mentions that the nude performances with Charlotte Moorman weren’t about nudity—it was about breaking that taboo. In those days, nudity in performance art was illegal. And he’s like, why? He was challenging that. That’s really the throughline in all of his work.

The other part of him that really resonated with me was how prescient he was. He was already uncovering, as early as the 60s, the world that we’re living in now. When I was about to really go into full-on production mode [for the film] in 2020, the world shut down and we were all reliant on screens to communicate with each other and stay connected. It was really illustrative of the humanistic and positive ways we can use technology to connect, empathize and communicate. That’s something Nam June Paik was always exploring and trying to champion through his own work.

Why she picked Nam June Paik as a documentary subject

In the West, a lot of people just don’t know who he is outside of the art world. I noticed that even people in cultural fields don’t know who he is, which was very surprising to me. In Korea, everyone—even people on the street—knows his name. I was like, “I would love for more people to know who he is and his artwork and what he contributed to history.” He's a really important figure, both in and also outside of the art world. That’s another thing that I tried to do with the film: to show how he was thinking about the world and how you can do that through art.

Why he’s the father of video art in more ways than one

Of course, he’s a pioneer in his field. But what really makes the father of video art is that he created this fertile ground by handing the tools and showing the way for younger artists. He really, really cared about the next generation. He would meet anyone and he would always try to help people. A moment I didn’t include, because the film was getting way too long, was him meeting this guy visiting from Europe who’s a science genius. Nam June Paik says, “Hey, why don’t you study at MIT?” and the guy is like, “I don’t really know anyone there, I would like to stay in America, but I don’t know how.” And Nam June goes: “Wait, let me see if I know someone there.” He's really trying to connect people. That's very beautiful and inspiring.

How she first encountered Nam June Paik

I knew his name growing up, because he is one of the more internationally famous Korean artists. Both my parents are Korean, though I only lived there for about one year when I was very young. There was this paper mâché object in the house that I would play with—it looks like a box—that my mom would sometimes put her jewelry in. It turns out it was made by Nam June Paik! My dad’s cousin is a Korean artist who lives in downtown Soho and Paik was a friend of theirs—he used to give his friends different objects or artworks.

On her own journey as a filmmaker

VICE was my film school. I studied comparative literature at Brown and then I graduated and moved to New York. I was interested in so many different things, I didn’t really know where to hone in my energies. My first job was around music and my boss was like, “I’m gonna leave this job, but do you want a recommendation?” That was for VICE. I started as a creative doing branded content. I was thrown into the deep end and had never done it before—it was sink or swim—but it was the best way to learn. I moved over to VICELAND before the TV channel launched, which was an incredible time. This was before ratings, so we could do whatever we wanted—it felt like Nam June Paik’s TV lab. I had a team and we went out and shot experimental things every day. I also did fashion and art-related content, working with i-D and Garage. Then I decided I wanted to try doing stuff on my own—I wanted to try to see what my voice looked like outside of that institution, so I was freelancing and working with different brands on my own while making this film.

The filmmaking process

I reached out to the Nam June Paik estate very early on, after starting the research and working really hard on the film, not knowing if I could make it but hoping that it was one day going to be made. Two years into it, I heard from them. It was hard. It took around five years to make. I had some great producers who helped me—I couldn't have done it alone.

What makes Nam June Paik so inspiring today

One of his quotes I love is: “Big bowl fills up slower.” As in, keep doing what you’re doing and don’t worry about anything else.

One of his quotes I love is: “Big bowl fills up slower.” As in, just to keep doing what you’re doing and don’t worry about anything else. When I speak to young artists who watch the film, they all really love the section where he’s like, “Successful artists have to keep making a work in their marketable style.” There’s a freedom to not having success too early—that’s something that resonates with a lot of young artists.

I think everyone can take something personal from his story for themselves. One of the beautiful things that I’ve heard is that he inspires people to create again. People are like, “Oh, I have this, like, corporate job at Nike now, but I’m actually an artist and after I watched the film, I wanna create again.” That’s been really beautiful. Why not just try stuff? It’s for you and it’s just as valuable—you’re thinking through the questions of yourself and the world around you.