In the city of Tunis, marriage ceremonies are affairs defined by glitz and excess, and the wedding photos taken on the day are often wooden and highly choreographed. Artist Aïcha Filali embarked on an embroidery project in response to this, taking images of just-married couples from wedding photos and placing them in a new environment, adding sunglasses to their faces and covering them in shiny jewelry and ornaments to emphasize the fact that these events are often more about pomp and ceremony than the couple coming together. Here, she and writer Sarah Souli question the order of priorities on these special days.

There’s a corner of the souq in Tunis that has long been my favorite: the bridal corner. Between the section for carpets and the Al-Zaytuna Mosque, there’s a bedazzled commerce section that’s full of brides and husbands-to-be and their entourages, picking out the perfect shade of drages (sugared almonds) to serve, or quilted baskets covered in yards of fluffy tulle. The theme is glam and, as all the merchandise is helpfully illuminated by blinding fluorescent lights, the sequins and glitter are multiplied, their reflective surfaces creating an entire miniature world of excess. A Tunisian wedding is not a place for minimalism.

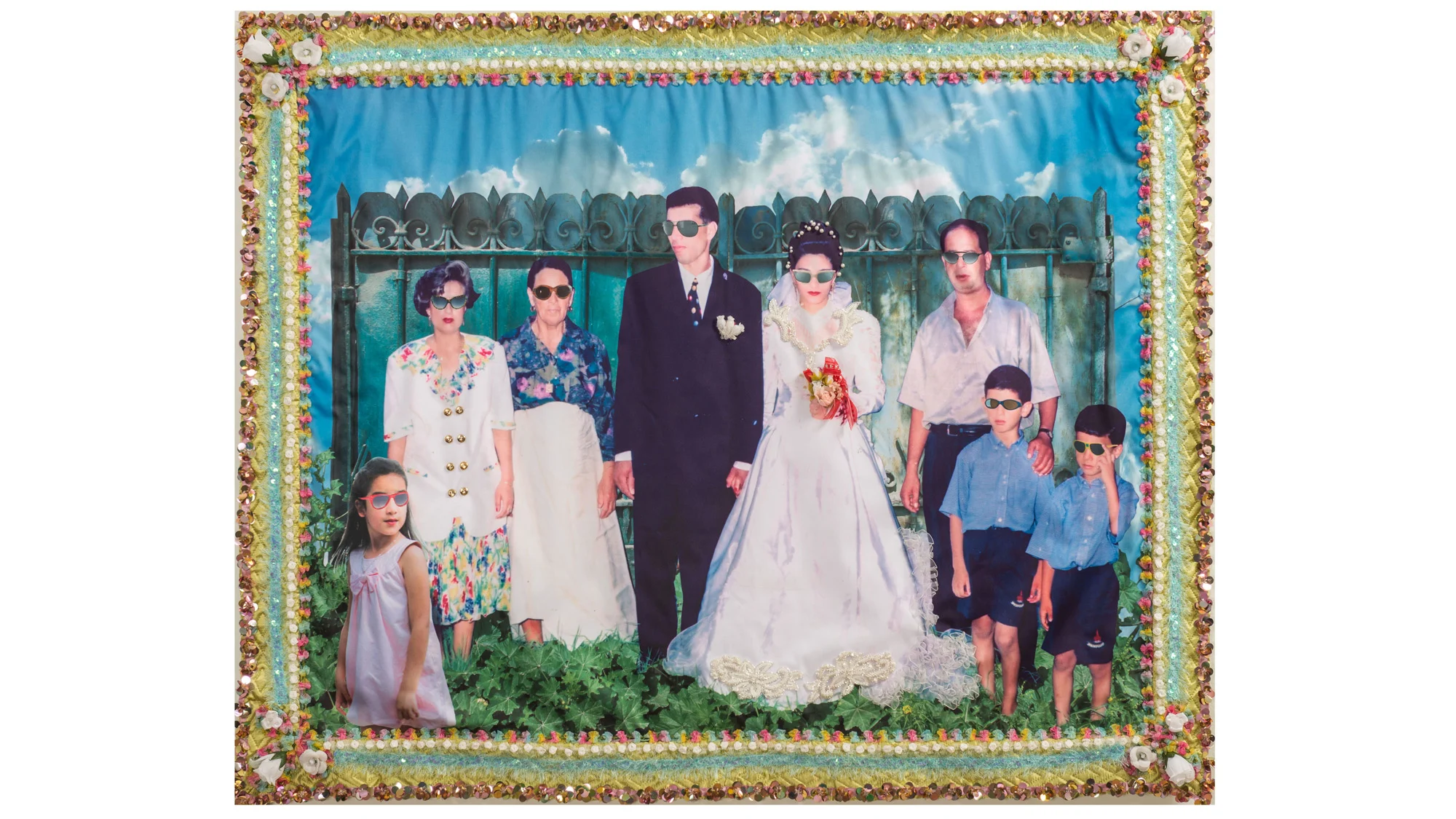

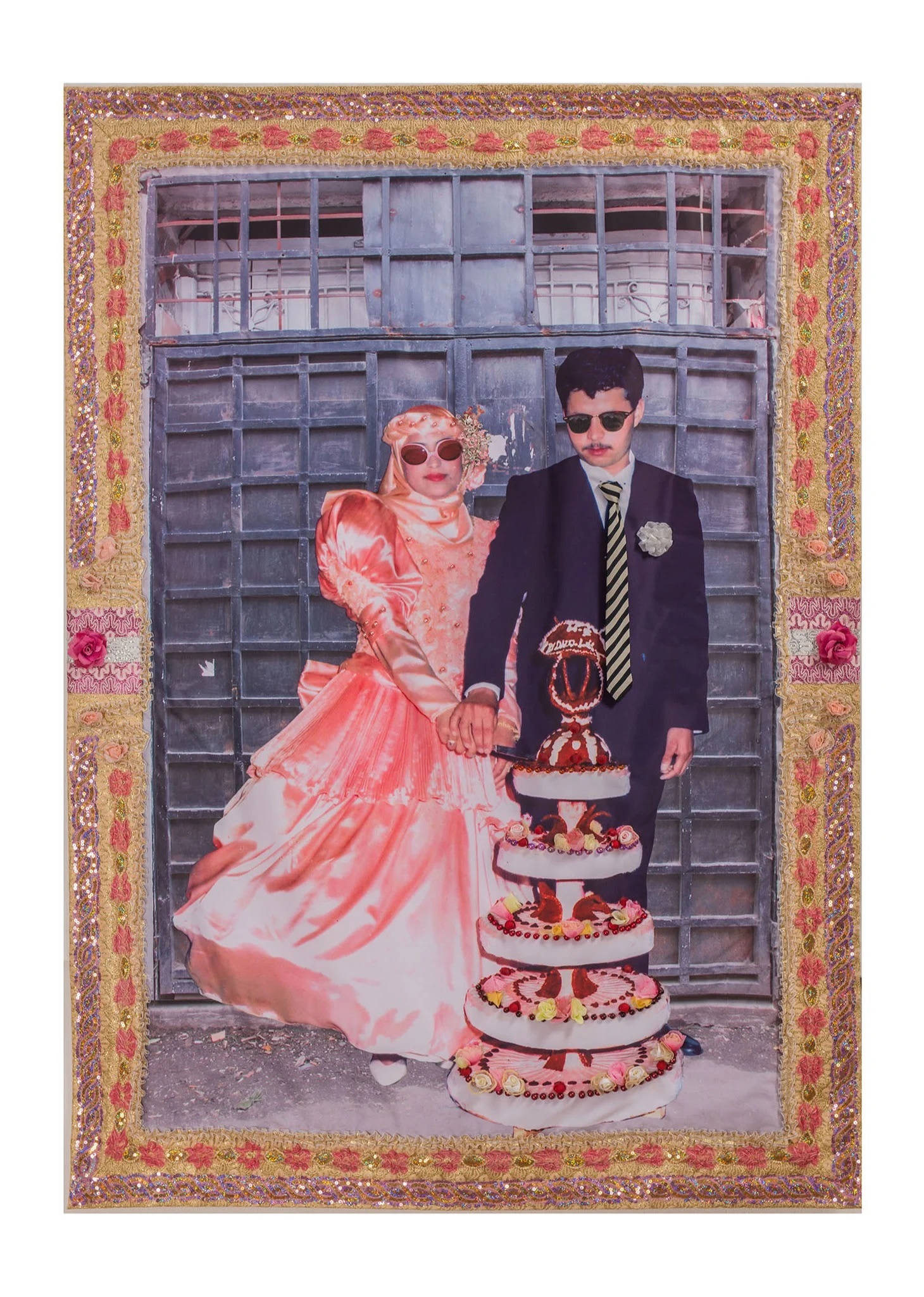

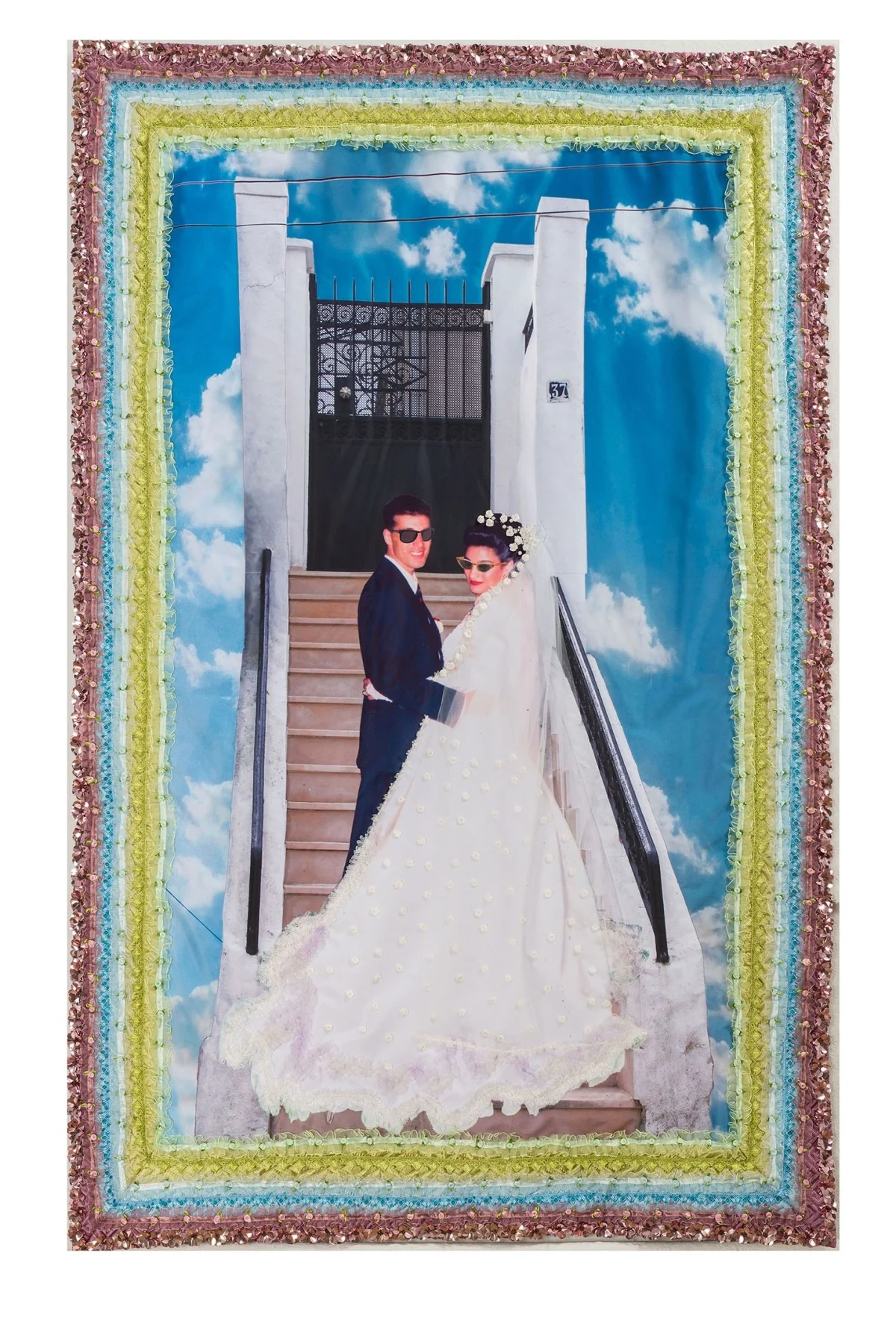

In 2011, Tunisian artist Aïcha Filali embarked on a multi-year project examining the performance of a wedding, and its most lasting souvenir—aside from (perhaps) the marriage itself—the wedding photo. Each of her works features a couple (and occasionally members of their wedding party) printed onto fabric and exaggeratingly embroidered with common accessories, such as jewelry or neckties.

Aïcha is one of the most successful multi-disciplinary artists in Tunisia. She was born in 1956, the same year that the country gained independence from France, after 75 years as a colony. Aïcha’s maternal aunt, Safia Farhat, was part of the first group of post-independence artists who lived through the process of decolonization. Farhat encouraged her young niece to pursue studies in art, and offered her studio space at the beginning of her career.

That Aïcha’s life, and thus her career, has spanned notable political and cultural developments in Tunisia is immediately apparent in her work, which is primarily concerned with social and political issues as they manifest in her surroundings. For Aïcha, making art is inherently political, though her work is marked by humor and tenderness.

During wedding ceremonies, it’s the photographer who dictates the poses to the couple and their guests.

“My starting points for this work are wedding photos and their stereotypical, frozen appearance. During wedding ceremonies, it’s the photographer who dictates the poses to the couple and their guests,” Aïcha explains. Those photos are less about capturing the more tender, loving moments between a newly wed couple, and more about immortalizing a highly choreographed one, which increasingly takes place in expensive wedding halls.

Aïcha took 20-year-old wedding photos and Photoshopped them, taking the couple out of the marriage venues and into places of residence. In one, a couple lean out of an Ottoman-style blue wooden balcony as if they were Romeo and Juliet; in another, a different couple stand in front of a wrought-iron fence.

The geographical displacement is a seeming nod to what happens after the festivities have died down—the bride returns home to the domestic duties of marriage. In Tunisian tradition, part of the seven-day-long wedding includes two henna ceremonies, at which intricate red patterns are drawn on the bride’s hands and feet.

It’s a celebratory moment that signifies the bride’s beauty and importance. As long as the henna stays on her, she’s treated like a queen, even at her in-laws’ house. However, it doesn’t last. There’s a common saying that when the henna fades, the bride becomes the wife—she starts washing dishes and making beds and folding laundry. The electrically lit wedding dims into memory.

I want to understand the image that everyone wants to convey of themselves.

For many Tunisians, the wedding—and the performance around it—is of critical social importance. It’s less about the couple as it is about the family or even the neighborhood. A wedding is a means of communicating social standing. Economic situations are pushed to the side, money is saved or borrowed, and many weddings end up being splashy, expensive affairs meant to signal a level of prestige. “My aim in expressing myself is to depict Tunisian society, and draw critical portraits of it, each time through one of the material extensions of society, which are most often everyday objects. This is how I think I make ‘engaged art’,” Aïcha says.

“I’ve always been very attentive to such objects in our society for how they help us understand our way of living and the image that everyone wants to convey of themselves,” she notes.

The wedding is about how other people will see you, which is why Aïcha’s use of sunglasses to obscure the eyes is so subversive. Each face is hidden, even children’s, compelling our gaze toward the theatrics of the wedding. We can’t understand if the couple are happy or scared or regretful; we only see the pomp around them.

“It’s also a nod to the common practice in some countries in the Gulf, where advertisements with models are acceptable only when they wear dark glasses,” explains Aïcha. “It’s the idea that the eyes contain the soul, and a face with masked eyes circumvents the Islamic prohibition of depicting human figures.” In Aïcha’s works, the results are alternatingly spooky and funny. In each, though, the posture of the couple remains fixed and frozen, and there is always a degree of physical separation. The individuality of each couple is minimized through the stilted choreography; the sunglasses only reinforce this.

Looking through Aïcha’s works, I’m immediately brought back to one of my most prized family photos, of my parents’ Tunisian wedding in 1987. Both are dressed in traditional outfits: my Tunisian father wears a cream vest and jeleba with off-white embroidery, while my French mother has chosen a full gold look with blue eyeshadow and long red nails.

They were already legally married abroad; this was a ceremony meant to appease the family. The kitschy glitz is exactly on par with the typical wedding photos found in Aïcha’s work, save for one difference. They didn’t have a professional photographer and no one dictated my mother’s moves. She’s leaning over and kissing my father on the cheek.