Photographer Abbas Raad is one of many creative voices shifting the narrative of Iraq, a nation rebuilding after years of occupation, resource-exploitation and misrepresentation by Western media. He tells writer Dalia Al-Dujaili how he hopes to capture intimate moments of religious worship in the country, and to highlight the beauty of the place and its people.

As this interview has been translated from Arabic to English, some words in quotes have been paraphrased or substituted for lack of a direct translation.

Iraq remains a place shrouded in mystery and misconceptions. Once home to the first civilizations on earth—Sumerians, Assyrians, Babylonians and Akkadians—and seeing the rise and fall of the Abbasid empire, under which Baghdad led the Golden Age of Islam, the nation has since been the source of much geopolitical tension since the discovery of its vast oil supplies. Today, Iraq is rebuilding from decades of war and recovering from gross Western misrepresentation. Meanwhile, Iraq’s creatives have been largely ignored on the global stage. But this generation is utilizing social and independent media to make sure that changes.

In a world where Islamophobia is still rampant, perhaps now more than ever, and the word “Muslim” is considered a potentially threatening or dirty one, Abbas Raad’s lens conveys a very different story, one tasked with fostering a sense of community and understanding among not only Iraqi society but a global audience.

Raad began his journey in 2017, picking up the practice from his friends after leaving his studies due to difficult personal circumstances. “This led to some psychological isolation,” Raad tells me, “and the only treatment was the camera.” Starting close to home in Dhi Qar, neighboring the important port city of Basra in the south, Raad says his main motivations lie in highlighting “the beauty of Islamic buildings and people through shadow and light.” His images literally shine a spotlight on the worshiper as they seem immersed in their surroundings, an often small figure amidst an engulfing spiritual backdrop reflecting the teachings of Islam—that there is no one greater than God, not even man.

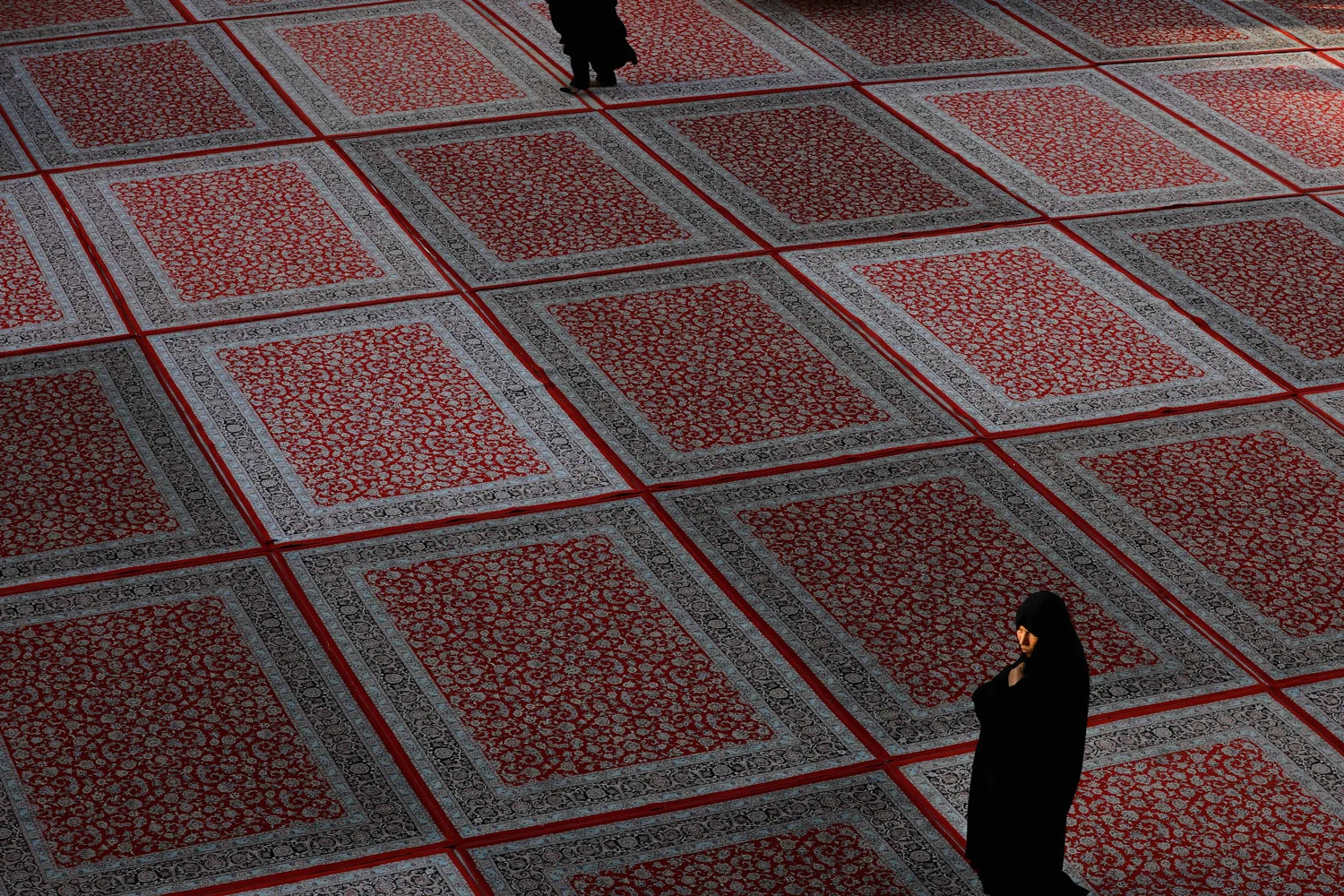

In one shot, an imam’s side profile sits in the bottom corner of a larger portrait of a mosque’s ornate archway depicting classically Shiite architecture and mosaic stones. Raad tells me the striking lighting contrast of his work “plays a vital role in conveying artistic and spiritual beauty, and also in religious activities [by] highlighting the details.” The light seems to play with the building and the figure, casting bulging shadows which leave a beam of light revealing the imam’s posture in an act of devotion as he reads from the Quran whilst obscuring his face in an almost everyman portrayal. In another similar frame, the camera takes a bird’s-eye view of a woman staring out of shot walking across a field of red rugs laid for prayer.

“I try to understand the place itself and sit at different angles so that I can see how the shapes and lines interact with the light at different angles,” Raad tells me of his practice, “and then look at how the shadows are created and how that reflects the essence of the religious ritual.” In another shot made popular on social media, a young woman stands and faces the camera holding a white tulip amidst a sea of seated women with their backs to the camera holding pink tulips—a garden of sorts—in a ceremony named “al takleef al shar’i lil hijab,” where they celebrate the girl’s wearing of the hijab. The scene is almost theatrical in its form whilst remaining documentary in its purpose. In portraying his figures as small parts in a wider web, Raad also inadvertently argues for the annihilation of the self in favor of the many, or the community, a cornerstone of almost all Arab and Eastern cultures.

“Because of the environment in which I live, the sect I belong to (Shia Muslims), and my relationship with God, the religious rituals of this sect attracted me,” says Raad of his subject matter. “Shadow and light are the way in which I express these special rituals and [moments of] worship,” he says, since he believes the lighting of his images depicts the way worshipers merge with their practice. “When true believers pray, you can see that they go to another world.”

Raad emerges as one of many artists, thinkers and creators in Iraq or of Iraqi descent who are adamant on rewriting the too-long established synonyms of Iraq, such as violence, incivility and emptiness. The self-taught photographer hopes for a future in Iraq with artistic infrastructural change for young people, such as centers for the arts with opportunities to learn photography. For now, the country’s artists and photographers rely on each other for support, guidance and skills enhancement; “I am surrounded by a small group of special photographer friends who constantly help each other out,” Raad tells me.

Iraq has historically been and remains an incredibly diverse nation. “Despite the wars, political conflicts, and the multiplicity of religions and sects,” Raad says the myriad of emerging photographers has still not been able to capture Iraq’s reality and make the wider world familiar with “all the details of this ancient country and its ancient civilization.” But coverage on the country has indeed come a long way since the days of colonial-style anthropological imagery or the subsequent war photography produced there, and quotidian joy is emerging within images of Iraq. Looking to the future, Raad hopes to use photography to “break the taboos that exist in my society,” and “to travel to the capitals of the world, continuing to document the deeply intimate yet necessarily communal act of prayer and worship.”