Growing up in Norway as one of the only Black people in her family, Frida Orupabo rarely saw images of Black women that empowered their subjects. Even from an early age, the white gaze felt suffocating to her, and she took note of the way photography was often used as an oppressive weapon that dehumanized or sexualized Black bodies. Now, as an artist, she’s taking old photos, many found in colonial archives, and repurposing them, creating new images that alter the power dynamic and give their subjects a sense of agency. She tells Gem Fletcher about her hopes that, through her work, she might offer a space where our understanding of gaze, representation and ownership can be challenged.

“I see anger as fuel in the creative process,” says artist Frida Orupabo. Born in Sarpsborg and of dual Norwegian and Nigerian heritage, Frida was attuned from a young age to the ways images can incite harmful ways of seeing. “Being the only Black person in a predominantly white family (except my sister), I hardly saw any images of Black people, and when I did, they were often racist or sexist.” As a young girl, she began urgently collecting images from newspapers and books, constructing her own vision of Black life. This impulse to confront existing narratives, defy their violence and imagine new worlds is at the heart of her practice.

Throughout history, female anger has been political fuel. This rage is crucial, transformative and fundamentally change-making. It has the power to spark collective imagination and imbue empathy, yet it is profoundly discouraged, especially coming from women. “I want to show you how I'm feeling in all its complexities,” Frida says. “Without being consumed or concerned by the myth of the angry Black woman that characterizes us as aggressive and hostile without any reason or provocation. Anger is important and vital for survival.”

Throughout our lives, we’ve been conditioned to read images in order to understand society’s opinions about who counts. At their core, Frida’s magnetic collages show the role of images in determining who belongs, addressing the ways photographs are used as tools of power and exclusion and how, in turn, art can create justice. “Toni Morrison talks about the importance of writing the stories you want to read,” Frida says. “That’s a principle I try to work by. If it doesn’t exist, I feel the need to create it.”

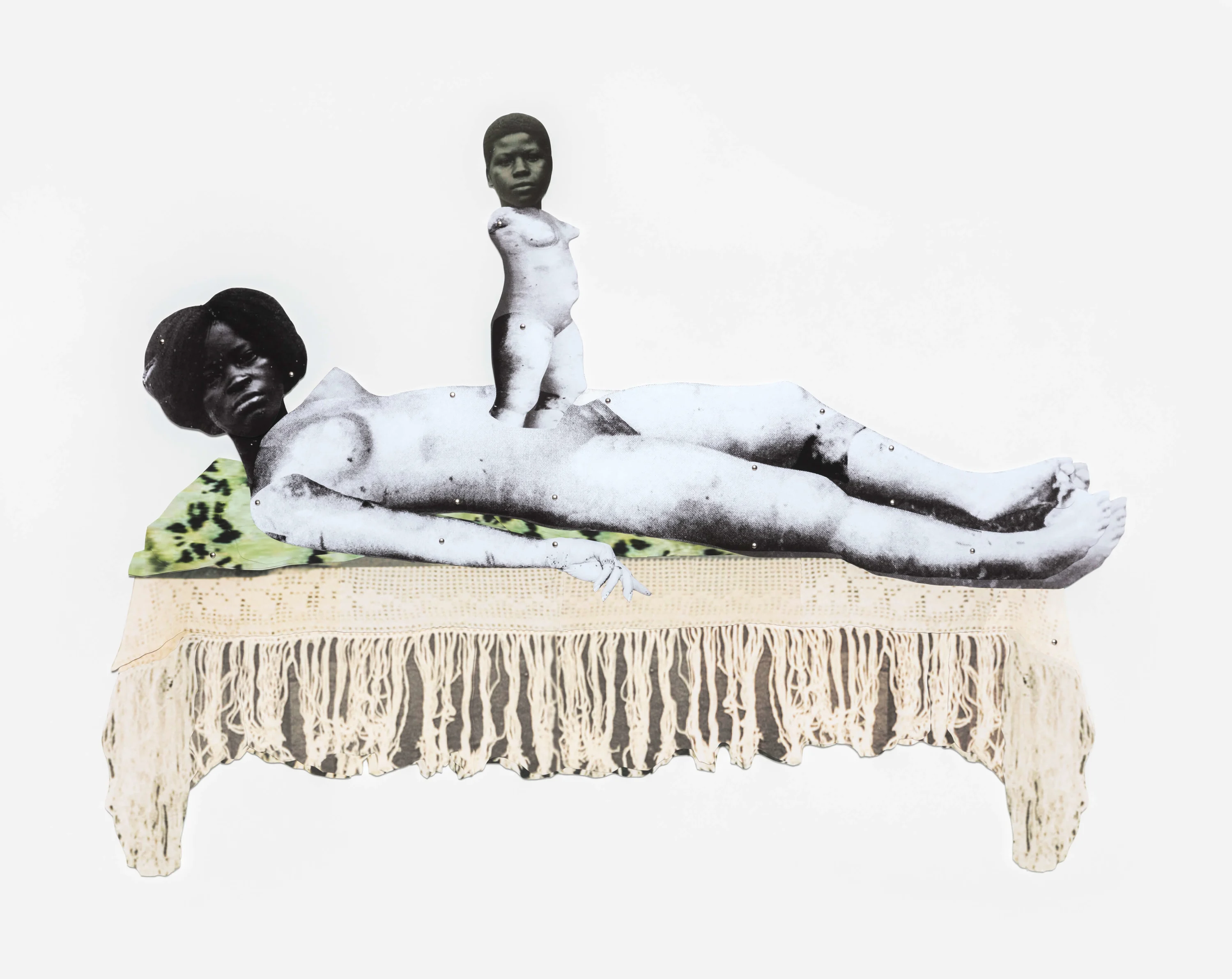

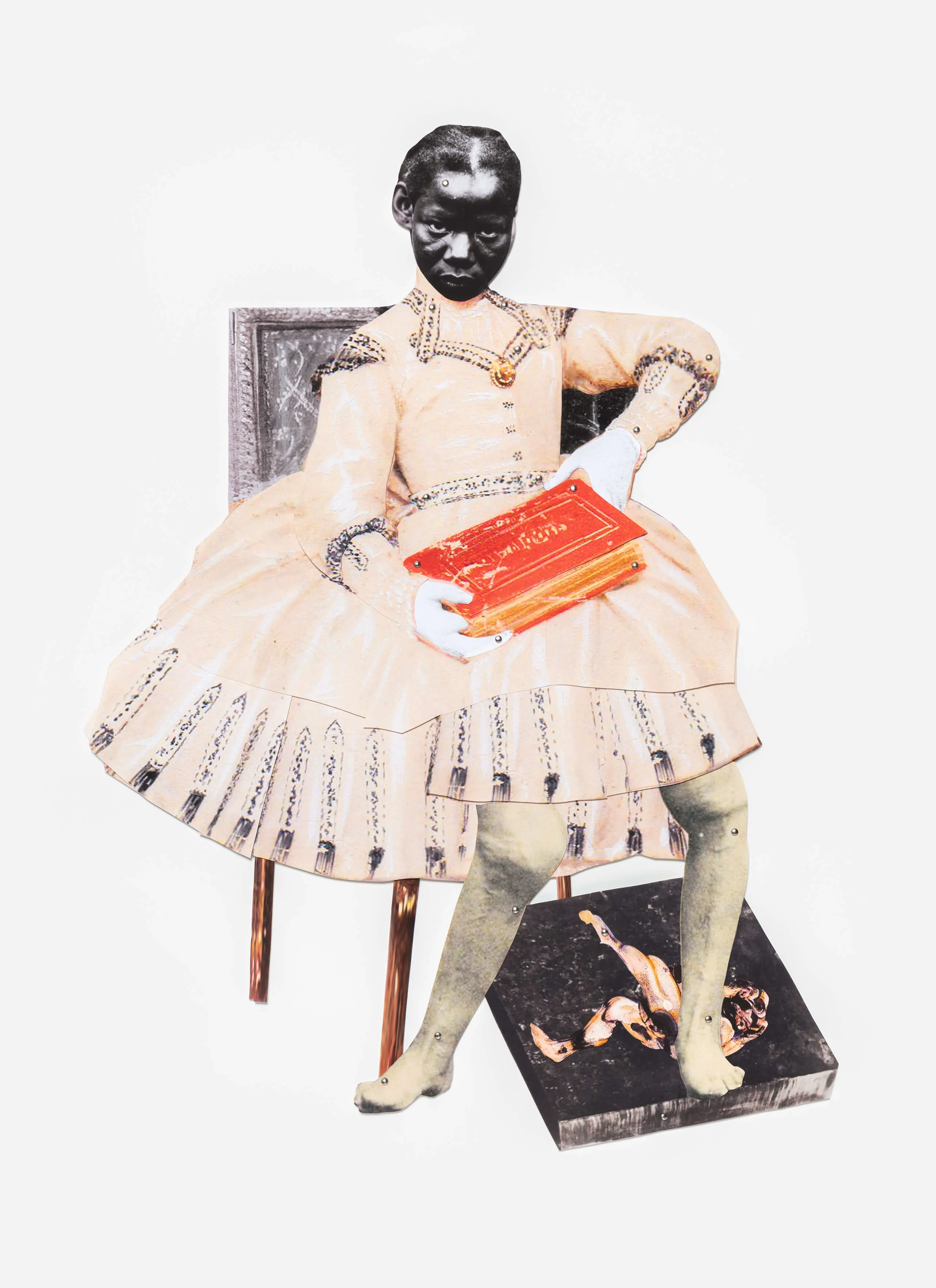

Cutting, stitching, and pinning are Frida’s primary processes. She takes found images of Black women—bearing the indelible legacies of colonialism—and liberates them from their violent context through collage. The archives she pulls from are sites of institutional power. They illustrate a period of rising colonialism where cameras were used as oppressive weapons, dehumanizing the Black body and fetishizing Black women in particular. This legacy of misrepresentation has impacted human rights, politics, identity formation, and the visual construction of race.

In Frida’s visual world, she confronts this traumatic legacy, illustrating the ways it has impacted her life while creating the possibility of resistance. The work isn’t comfortable—but that’s what makes it so radical. Her careful assemblages speak to reality, showing women vulnerable, and sometimes in pain, while also exhibiting their strength and clarity. Their liberation is rooted in acknowledging that multiple conflicting truths can exist at once.

She grounds figures in familiar, domestic settings, using accents like a bed or dresser while ensuring every character claims their own narrative, history, and feelings. Their defiance can be seen in their body language: how they dress and hold themselves. Each piece offers new readings and meanings, constantly creating friction between self-representation and imposed representation.

“I've always been interested in layering pieces that are not meant to sit together,” Frida says. “It's a way to bring Black subjects into spaces that they’ve previously been excluded from or made invisible in.” The result is a kind of material poetry. A collision of past and present that speaks to the pursuit of personal revelation and the enduring nature of human resilience.

Like many artists, Frida’s journey was unplanned and unexpected. She studied sociology and started a career in social work, making art in her spare time. In 2013, she began publishing the work on Instagram under the handle @nemiepeba. Initially, the platform was a safe space to collect and store ideas, a necessity due to her self-described “terrible memory.” Over time, it evolved into a vibrant and experimental laboratory, a place to make visible the connective tissue of her practice. Here, legendary filmmaker Arthur Jafa discovered her work in 2016 and invited Frida to participate in his exhibition A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions at London’s Serpentine Gallery.

“At the time, working as a social worker was my life,” Frida says. “I was happy doing my creative work on the side. Arthur’s invitation to exhibit really pushed me. I quit my job two years ago. Now I feel like I’m in the right element.”

Her process of art-making is rooted in self-actualization, sitting at the intersection of the personal and political. “I also think of my work as creating and sustaining one’s core, and that in exploring my personal narrative and identity, I also explore collective memory and history.”

Creating images that are intimate and personal is critical for Frida. While the work of Kara Walker, Audre Lorde, and Toni Morrison informs her practice, it's the empowering act of centering her own experience that truly activates her work. “It’s as much a question of what my collages have to offer me,” says Frida. “They are a space to both question and exclude the white gaze—a gaze that felt suffocating in my own upbringing.” What is so captivating about Frida's work is the defiant gaze of the women she pictures. As she mines colonial archives for images, she seeks out moments of resistance. “To look back is to refuse to be made into an object, a refusal to be racialized, or sexualized,” Frida explains. “It's also a way of making the onlookers aware that they also are being seen.” This active confrontation with the viewer is essential. It triggers an internal dialogue, questioning how we see and why, creating new possibilities for consciousness.