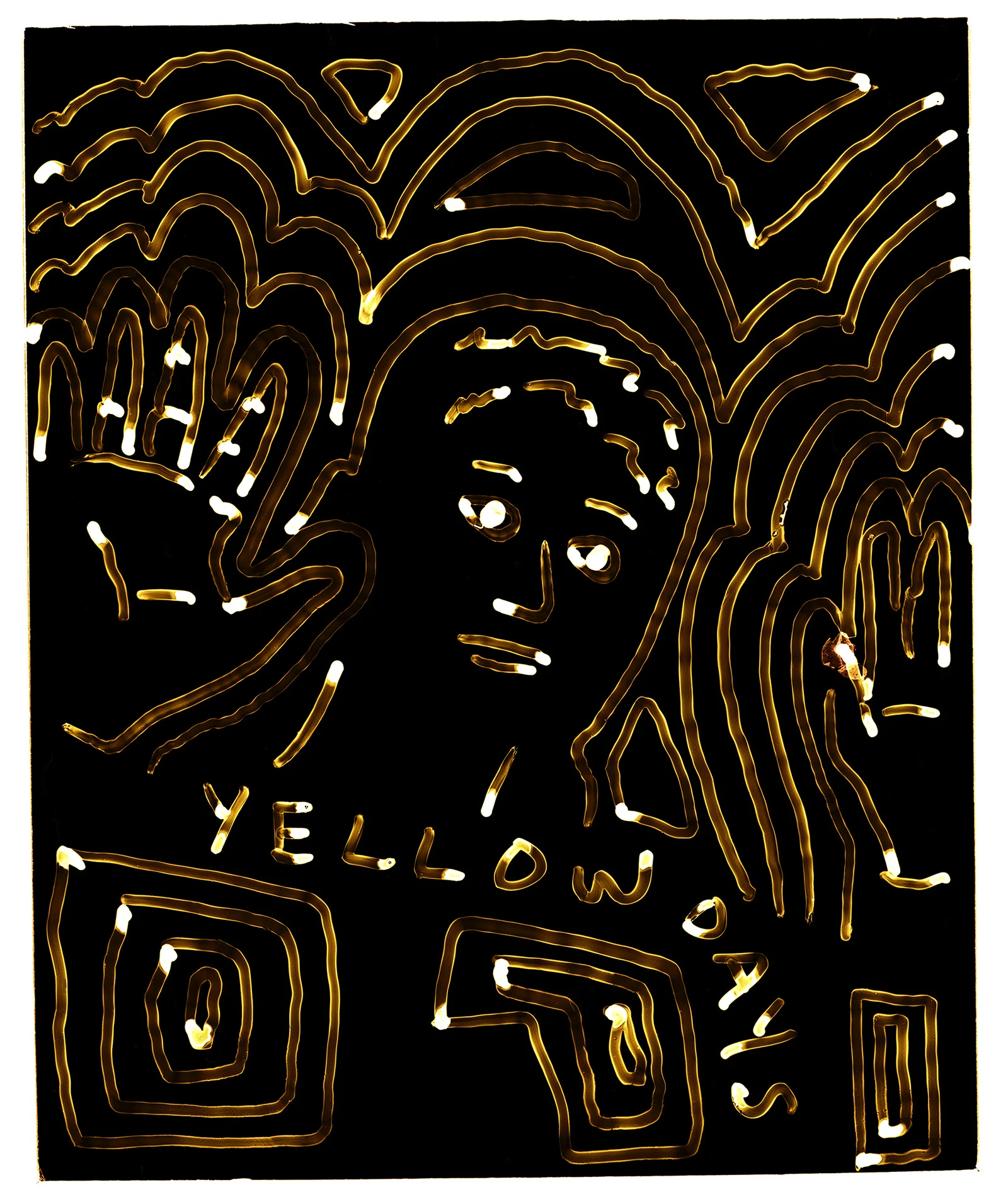

Yellow Days is the perfect antidote to every song you’ve ever heard on the radio that sounds exactly the same. Bored by convention and tired of musicians not actually playing any music, the multi-instrumentalist is on a mission to bring back the good old days and the magic that happens when musicians come together to create. Writer Alim Kheraj finds out how he went from making music in his parent’s garden shed to becoming the industry’s great new hope.

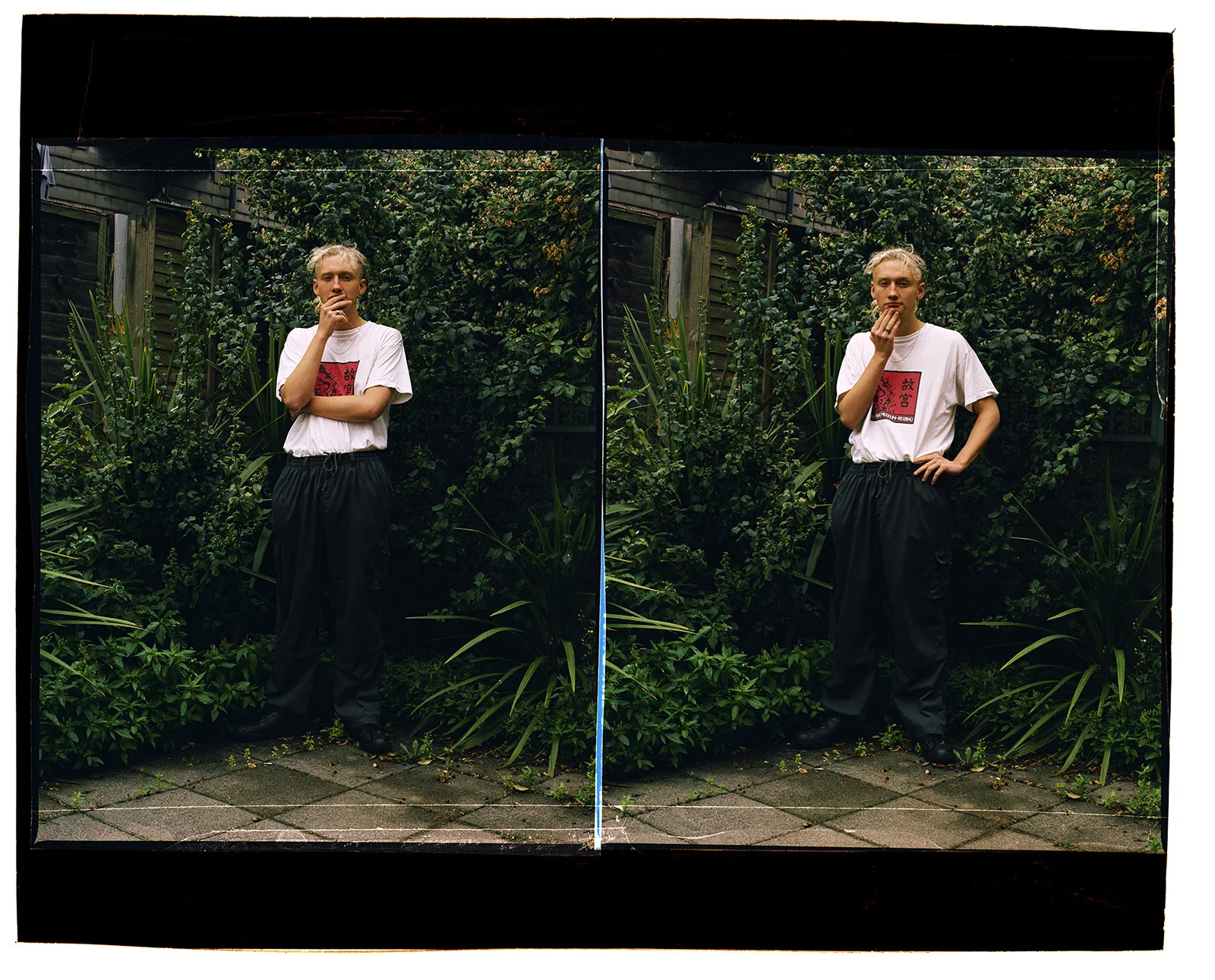

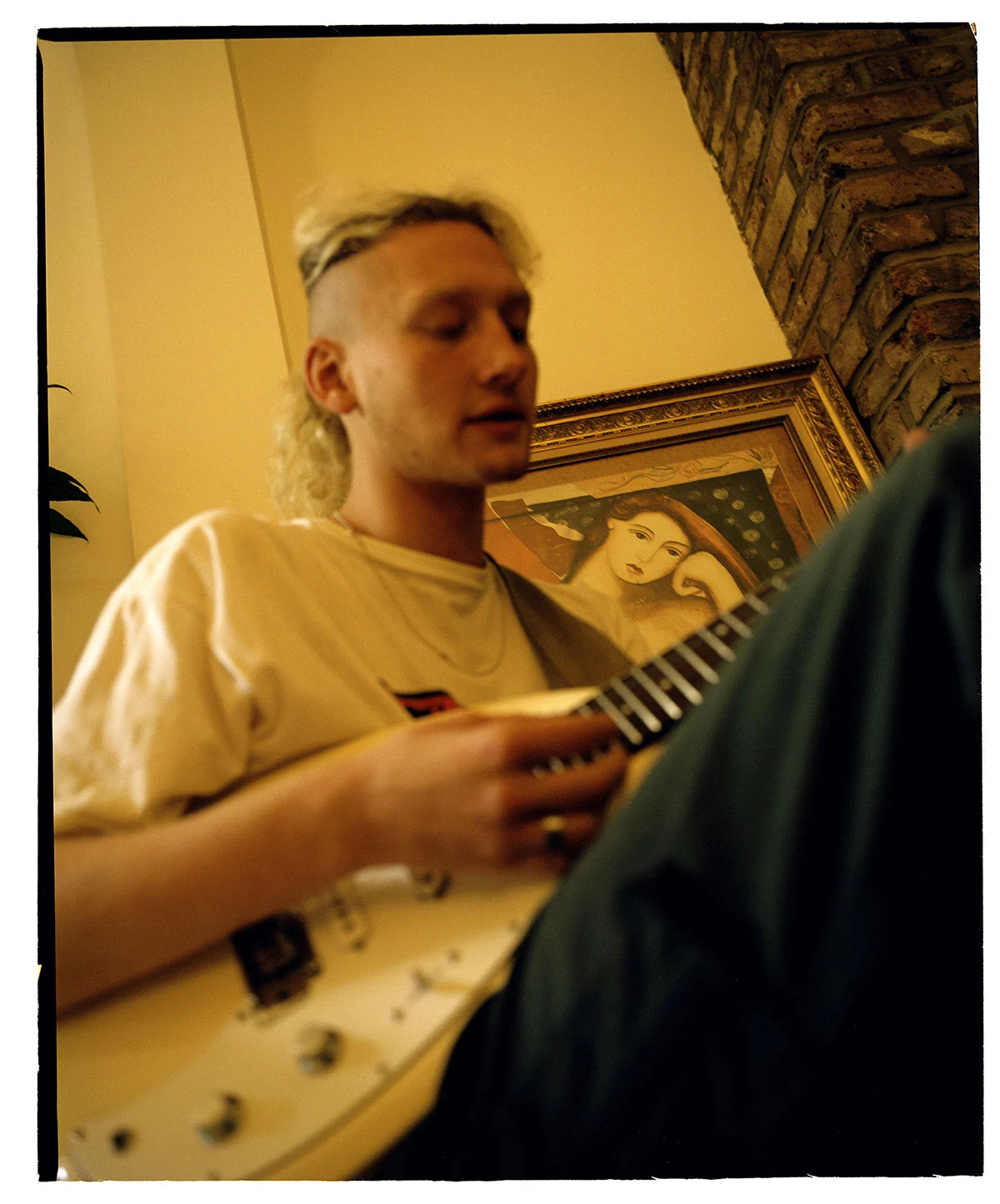

Photography by Luke & Nik.

For the past few years, Yellow Days, the musical alias for 21-year-old George van den Broek, has been trying to recapture the 1970s. “It's this era of music that I wasn't that aware of and that I hadn't listened to much growing up,” he says. “I was always more of a blues and soul head. Now, I've got into my funkier music. It's all of these guys who seem to be these secrets of the '70s. They were a player in this or that band, but then got a deal to do a couple of solo records and got all their favourite cats together. It didn't really sell at the time, but nowadays you try and buy a record and it's worth £300 because it's understood that these guys were the secret geniuses of their generation. Their music took me to a place where I realized that I needed to recreate that environment. I needed to build a great band and write great compositions and bring it together on this level.”

Of course, we’re not in the 1970s at this moment in time. We’re sat in George’s kitchen in his charming terraced house in London’s East End. It’s a rare face-to-face interview following an intense period where meeting other human beings felt almost clandestine because of the global COVID-19 pandemic. Although restrictions have eased and people are allowed to gather, albeit in small quantities, it feels bizarre to be sat with someone in their home having a conversation about reviving bygone musical eras.

Nevertheless, George is at ease. Slouched in a chair at his dining table, the back door open so he can smoke hand-rolled cigarettes and the occasional joint, he seems unfazed by the presence of an outsider in his home. But George has become adept at handling the unexpected, and all the ways that life can suddenly switch on you and turn your world upside down.

Born in Manchester but raised in Haselmere, a town in Surrey an hour from London, George first started playing music at 11 when he was given a guitar for Christmas. By the time he was 16, he had taught himself not only the guitar, but also bass, drums and keys, as well as mastering production software like Logic. After recording and releasing an EP, the woozy Harmless Memories, he retreated into the garden shed at his parent’s house and began to focus on music full time. Signing to London label Good Years and later to Columbia Records, he went to work on his follow up, 2017’s Is Everything Okay In Your World?

Those two records, soulful, deeply honest and imbued with George’s experiences with depression, anxiety and the restlessness of life growing up in a small, rural English town, connected with people around the world. He soon found himself booking festival slots and tours in the US, Australia, Japan and the UK. “I was thrown in at the deep end,” he says now. “I was just a 16-year-old kid who grew up in the countryside of England with this manager I had just met. I had never been anywhere outside of Europe before. All the travelling I do for music is the first time I've been to a lot of places.”

Up until that point, Yellow Days had been a project almost entirely conducted alone; while George had worked on production with his friend and mentor, Tom Henry, the writing and recording of the music, including all the instrumentation and composition, had been done in isolation. Yet, things were beginning to shift.

“I decided that I wanted my own space. I started going out into the world jamming with people, like a bunch of people who are all underground session musicians,” George recalls. “People like Robert Glasper and others who had heard of me, for some reason. I met so many people and it made me realize that I was in a very insular place. It's great being a 'fuck you' dude who sits on his own. But…it gets lonely. There are so many people just like me who I can meet and hangout with and do fun shit with.”

Spending time in Los Angeles only solidified this. “It’s a cool place because it’s built up of a bunch of misfits,” he explains. “There are a lot of very nasty people, but that's like everywhere. There is pretentious bullshit. But fighting against that are these very cool and interesting people who are very humble. If you go out there you can get work. So there's a mass migration of musicians from all over the world. It's a place where people are only really similar because of the way they think. It's very human. England feels very historical. Whereas over there, they're are like, 'Fuck it, we're going to build a city in the desert.' They don't give a fuck. You could call it artificial, but I just think of it as man-made, which isn't necessarily a bad thing.”

George says that he avoided the trappings that many young artists who suddenly find themselves transplanted in LA fall into. Having done a number of songwriting sessions when starting out, he knew that pop writing wasn’t for him. “I'd go and do these sessions and you'd meet a dude who'd say, 'So what is the subject matter?' before we'd even picked up an instrument,” he says, his tone indignant. “I knew I was in the wrong room. For me, you make a piece of music that invokes a feeling, and then the subject matter comes to you. Maybe once the tune is playing, you can then say, 'I feel like this is a song about not giving a shit.' If you walk into a room and they ask what it is you want to make a song about, that's when I know I'm in the wrong place. That's how guys who make number one hits start. While the artist is writing the song, they're over there playing everything.”

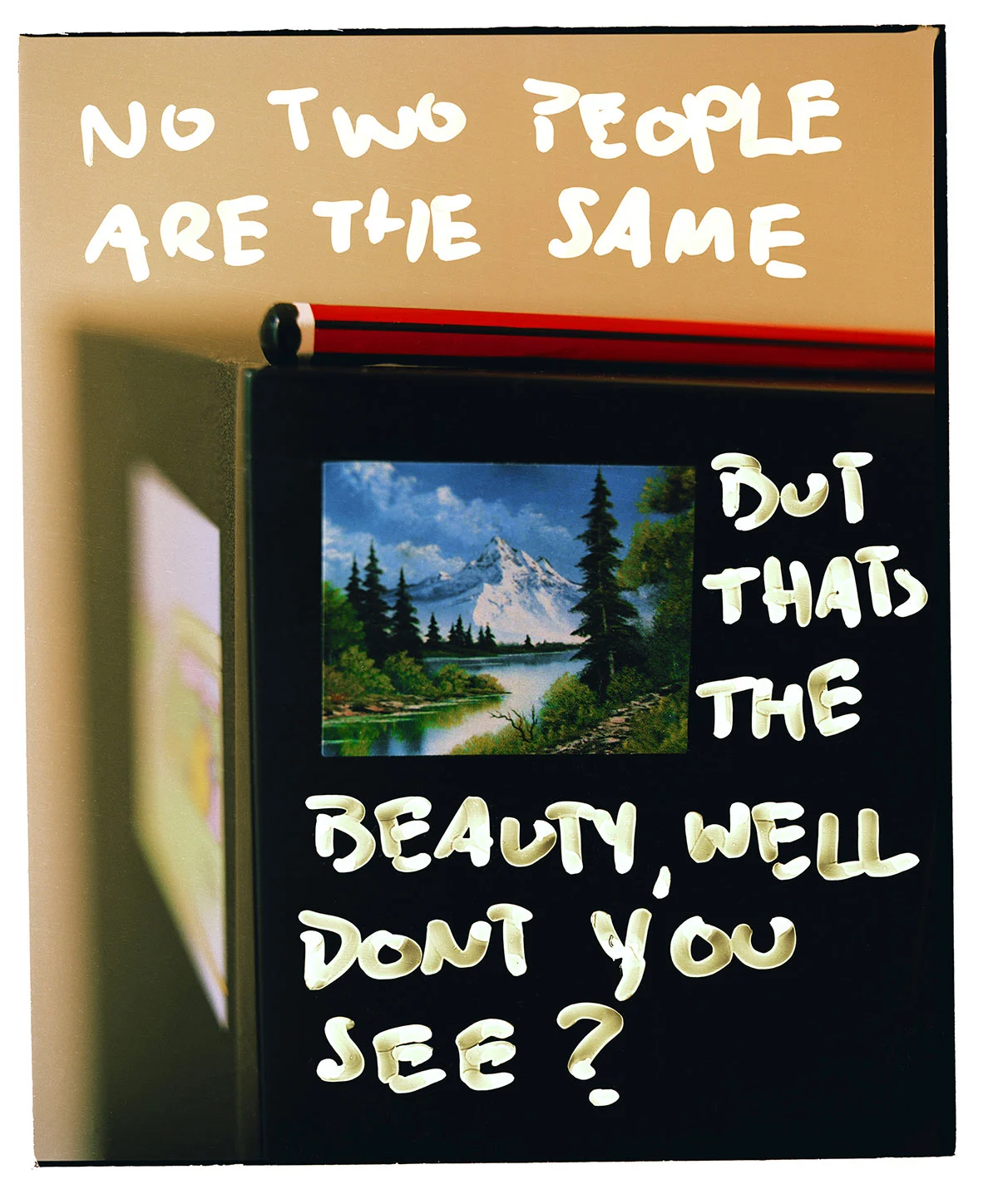

Such songwriting works for some artists, especially those who find their songs in the upper echelons of the charts. George, however, finds them almost sacrilegious. Music, he believes, is in “a bad way.” Technological advancements in recording and production have nearly eradicated the need for real, live musicians and created a culture of egotism. Technology, he says, “pushes people away from each other, like it so commonly does in a lot of other senses. In music it's undeniable; people do not want to collaborate. A lot of producers would make incredible music if they just called their buddy up or used people to their strengths, instead of trying to take all the credit. They’re almost trying to do it so they don’t have to pay someone to do bass if it's a hit. They can take all the money. That shit sucks!”

There is an irony in this ideological shift, and George laughs when confronted with it. “My early music is good, but, personally, I wish I could go back and do it as a band,” he admits. “It's just something I've realized, and for me it's principal in terms of the way that I want to make music. I still like to write everything; I'll compose the whole song – the bass line, the groove, the trumpet line – but then I'll get others to play the instruments. That's real music. It's not real until a real person plays it. There is so much pop music that you hear where there is no band. It's all fake. There's a drum beat but no drummer. There's a bassist, but no one's actually there. They use sounds that create the impression that there's a real person there. That's the difference between modern music and old music. People had to play it then. Music was a thing of people and community and relationships. That's been lost. Now I realize that, I want to push for it.”

His shift in creative mentality was accompanied by an easing in his struggles with his mental health. George says that while recording his first two records, he was in a rotten place. “I was going through a lot of bullshit. When I was in that garden shed, I was not feeling great.” Since then, he has fallen in love. It has completely altered his life.

“I feel so at peace with myself for the first time in years and years, and I’ve started to see things in a nicer way. It's all about finding true love,” he swoons. His girlfriend, who he shares his house with, and who makes an appearance to make tea and drop off a sandwich for George, has helped him see the world in a new perspective.

“The people in your life who really care are going to be there for you if they really love you. That's what you need if you want to overcome these things. They'll give you such strength. They'll be patient with you. They'll help you,” he says. “You love them and you want to be good for them. Sometimes when you sit with yourself you can become self-destructive and you start destroying yourself on purpose. But when you're with somebody that you love, you want to be strong for them. I think there's really something to be said for that with people who have mental health issues.”

He is aware that it’s a path that not everyone will follow, and, as he says, “I don’t bash therapy.” It’s more that finding love has helped him build a philosophy for life: love, happiness, caring and sharing. It’s this that is the bedrock of George’s new record, A Day In A Yellow Beat, which is due this September. Opening with a sample spoken by Ray Charles about the state of the music industry, the album is a manifesto, of sorts, encapsulating all the ideas and beliefs that George now subscribes to. “I'm just out here trying to live life,” he states, “experience new things and be inspired. Artistic inspiration, for me, is everything. Feeling in love with the world, and all the images, colors and sounds that it gives off. All the living creatures and the sky and the sun and flowers. There's so much to be appreciative of, beyond just food and shelter.”

Despite his lighter disposition, the music still exists in Yellow Days’ universe. He’s described his sound as “upbeat existential millennial crisis music,” which fits. Yet, whereas before he might have submerged himself into that crisis, this record is almost didactic in suggesting an alternative. Songs like Keep Yourself Alive and The Curse touch on despondency, but soon pivot away to optimism, or at least a glimpse of optimism.

Still, the record does traverse uncomfortable territory, specifically the notion of lost friendships. “The album cover actually has a flower on it, which symbolizes lost friendship,” George explains. “I lost so many friends through becoming a musician and touring all the time. I got very lonely. The record I've written here is really about trying to break out of things and be bigger than life itself.”

This manifests itself in George’s ambition for the record, too. Along with working with his musical heroes like Mac DeMarco and session musicians who have worked with the likes of Raphael Saadiq, Frank Ocean and Kanye West, he has also drawn on the musical lineage of Herbie Hancock, Quincy Jones, Marvin Gaye, Don Blackman and Weldon Irvine. He’s solidifying his commitment to enacting a paradigmal refresh of how people create music, be that through live instrumentation, paying musicians a decent wage, or restructuring that industry so that the music can be made affordably while still being fully realized.

“People find music disposable,” he says. “It's like having a really cheap drink and just throwing it away. But if you had a nice bottle you might keep that. These records are not worth anything. They're made cheaply because it's about making the most profit that you can. Whereas back in the day, it must have cost a lot of money to make and that's why we cherish it. It's like a temple. It's time, effort, money, hardship and all those things that go into it. I personally think they should be expensive, and if you can you should do that. You'll make better art.”

He's still a young man, though, and there is time. He has an album to release, and that record has its own mission statement, too: “I'm trying to make a case for a bunch of the kids who I know have been listening to my music for years and have been tattooing themselves because they connect so deeply with my message and some of the things that I've communicated in the past about depression and anxiety. I hope that they listen to what I'm trying to do here: I'm trying to make a case for opening up and being a flower.”

He stops for a moment and grins. “I always say this to people that I know, and it's kind of silly, but you've got to be a flower. So many people in life close up. You've got to let it all go. You've got one chance. I want to encourage people, and myself in tangent, to be positive and to love life. That's the message of the record; it's about breaking out of a state of depression and trying to see the sunlight in the darkness.”