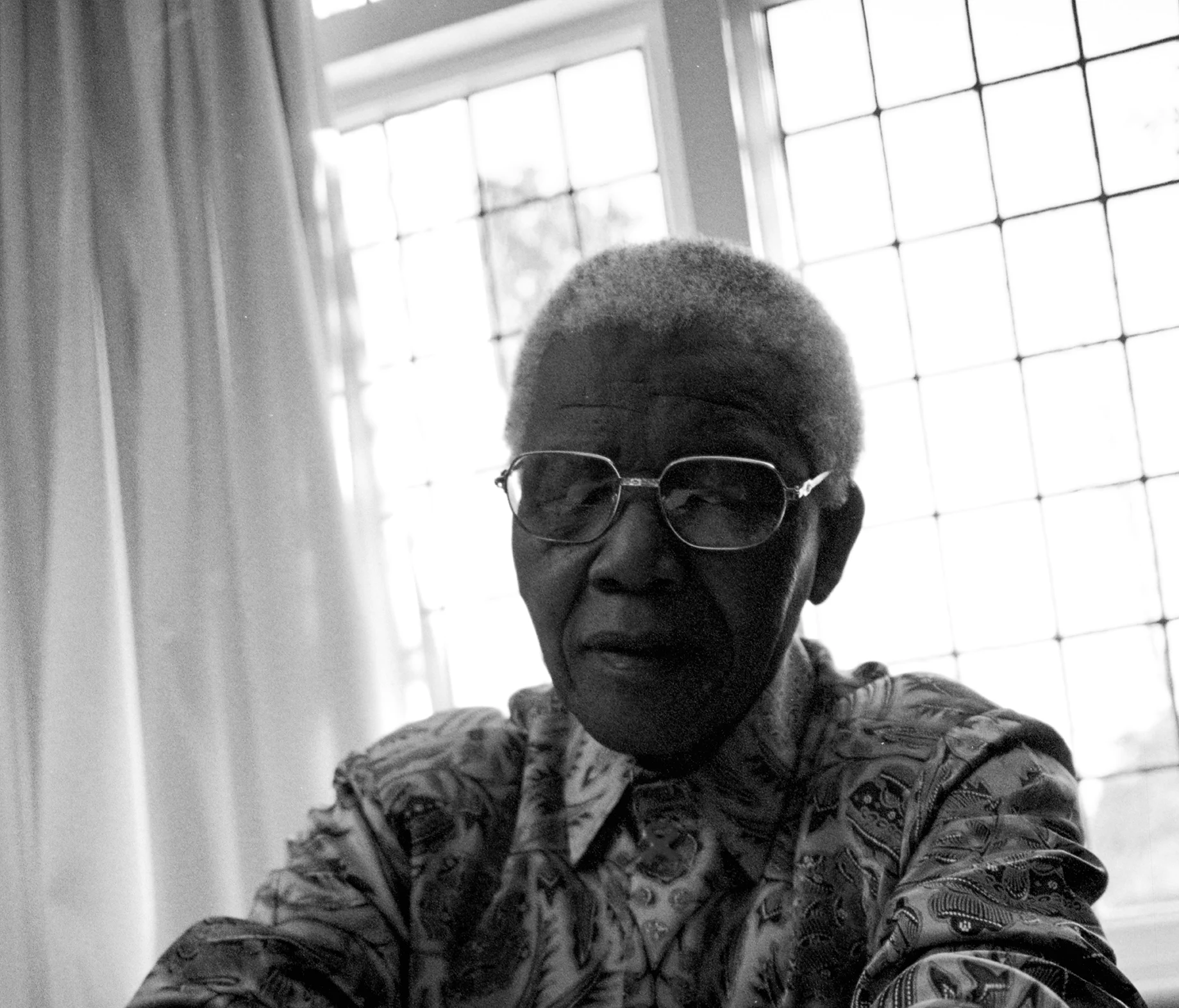

To mark the launch of these exclusive Nelson Mandela sketches, his daughter, Makaziwe Mandela-Amuah, tells Alix-Rose Cowie about her dad and the joy he found in art during his later years.

To find out more about Nelson Mandela's artwork and to buy original pieces, visit the House of Mandela here

A lot of people who were oppressed resorted to art or music to express themselves. Art is such a binding force. Without art which captures our culture, we don’t have history.

Nelson Mandela is one of the most important figures of the 20th Century. But the more someone becomes a symbol, the easier it is to lose sight of the person. It gets harder, but even more interesting, to try and work out what they were really like.

Mandela and his legacy have been discussed, dissected and glorified by hundreds of writers, historians and artists. His own book, The Long Walk To Freedom, opens a window into his mind.

But when he was asked in his later years to create a series of drawings, art became an outlet through which he could interpret his own life.

The Struggle series captured his memories of his 27 years in prison on Robben Island. The Homeland series — shown now for the very first time to mark what would have been his 100th birthday — goes back even further.

Retired and living in Houghton, Johannesburg, Madiba made the Homeland sketches based on fond memories of his childhood growing up in Qunu, a village in South Africa’s beautiful Eastern Cape. He had dreamt of retiring there, to spend his last days in the rolling fields, walking with his cows and sheep, amongst his ancestors.

Madiba is Mandela’s clan name. In South Africa in particular Mandela is routinely referred to as Madiba, a term of respect and affection that nods to his roots.

To the world, Mandela is known as a symbol of forgiveness, humanity and overcoming adversity. To South Africans, he is known as Tata, or “father” in his own language Xhosa. To his eldest daughter, Makaziwe Mandela-Amuah, he is dad.

In her own words, Makaziwe remembers how her dad embraced art in his later years, and explains how his interpretations of Qunu give the world a glimpse of the man behind the legend, and what he held most dear...

When my father retired as the president, he didn’t have much to do. I think for him, art was a good way of expressing himself or trying to come to terms with his history and his — I wouldn’t want to say demons but just coming to terms with his whole life.

I think he found it amusing that in his old age he could actually start something new. Tata used to say to us, “It always seems impossible until it is done.” And he thoroughly enjoyed doing it. My dad was always open to trying new things. Art for him was, in a way, taking back his own life, and saying — this is how I want to interpret my life. Because I can’t forget where I come from and where my spirit is.

If you look at the people who really pushed countries from one period to another and shifted the paradigms of a nation, it was through the arts. You look at Greece — it was the artists and the philosophers, it was not the politicians. A lot of people who were oppressed resorted to art or music to express themselves. Art is such a binding force. Without art which captures our culture, we don’t have history.

People think my dad was a politician and that Nelson Mandela just fell from the sky — that he doesn’t have a sense of place, a sense of belonging. For me, the Homeland sketches are very important for the world because they give a glimpse of who my father was holistically. How proud he was of who he was and where he came from, even though he came from humble beginnings. That’s what I want the world to see. Not just the politician.

Because of his incarceration, my father wasn’t very good at communication. But he would tell us stories about Qunu. One of the things he enjoyed most when he was in jail was when my aunt came to visit, because my aunt talks a lot. My aunt would tell my dad about all the village gossip and he really enjoyed it.

Qunu is a beautiful place. It’s a spiritual place. It’s very calming. You forget how beautiful it is when you’re not there. Qunu meant a great deal to my father. He did not talk too much about it but he had beautiful memories of Qunu. He wanted his last breath to be there. He said when he was in jail that he didn’t want to be buried anywhere else but Qunu, and if you buried him anywhere else his bones were going to shake.

When you see the sketches, you are taking a look at the things that meant a lot to him. The landscape, the cows — my dad was very fond of these cows. Even when he was in a wheelchair, every day he would tell the security driver to let him go and see the cows. That’s another side people don’t know about my father, that he was a farmer. He liked farming and growing vegetables. So those hills and huts where he grew up with his cows are all fond memories.

People think my dad was a politician and that Nelson Mandela just fell from the sky — that he doesn’t have a sense of place. That’s what I want the world to see.

When you come to the Homeland series, it is about asking, who am I? There is not a single human being who doesn’t have a longing to know who he or she is, where his or her roots are. Because that anchors you.

When you know who you are and where you come from, you can understand yourself more and fit better in society. Especially at this point in time when there is a huge focus on Africa and people going back to their roots. I think the sketches will mean a lot to people in terms of asking who they are and where they come from. And releasing the Homeland series at this point in time is very important as it will remind people it doesn’t matter where you come from, you can break the glass ceiling if you want to.

Tata was down to earth, very human. He’d tell us children that we have to strive to be better than him. I think it’s big shoes to fill in terms of what he’s achieved but I think you have to set a goal.

I’m very proud of my dad and what he could achieve in his old age. I’m 64; I don’t count myself as old. I feel strongly that it’s just the beginning of life.

I went into business and I’m surprised by how creative I am. Sometimes we doubt our ability but all of us can do it. Just take that leap of faith. His sketches are one way of telling me that my dad is still around with me.

Portraits of Nelson Mandela by Grant Warren