Cape Town-based photographer Imraan Christian is as much a healer as he is a photographer. And he is on a mission to create a new mythology for the youth of South Africa’s indigenous communities, who, as a result of centuries of colonialism, have been deprived of their own history. “Where we find historical loss, the only thing we can do is draw from our culture to reimagine and recreate,” he says. In his series Ruh, which translates from Arabic to “soul,” Imraan draws on shards of often-forgotten culture to create something entirely new: a fantastical world of indigenous gods, queens, and heroes playing their part in tales that can fill the gaps in a history that’s been ravaged by persecution. He tells Katie de Klee how he hopes that by imagining a new mythology indigenous people can see themselves in, he can help them see their potential differently.

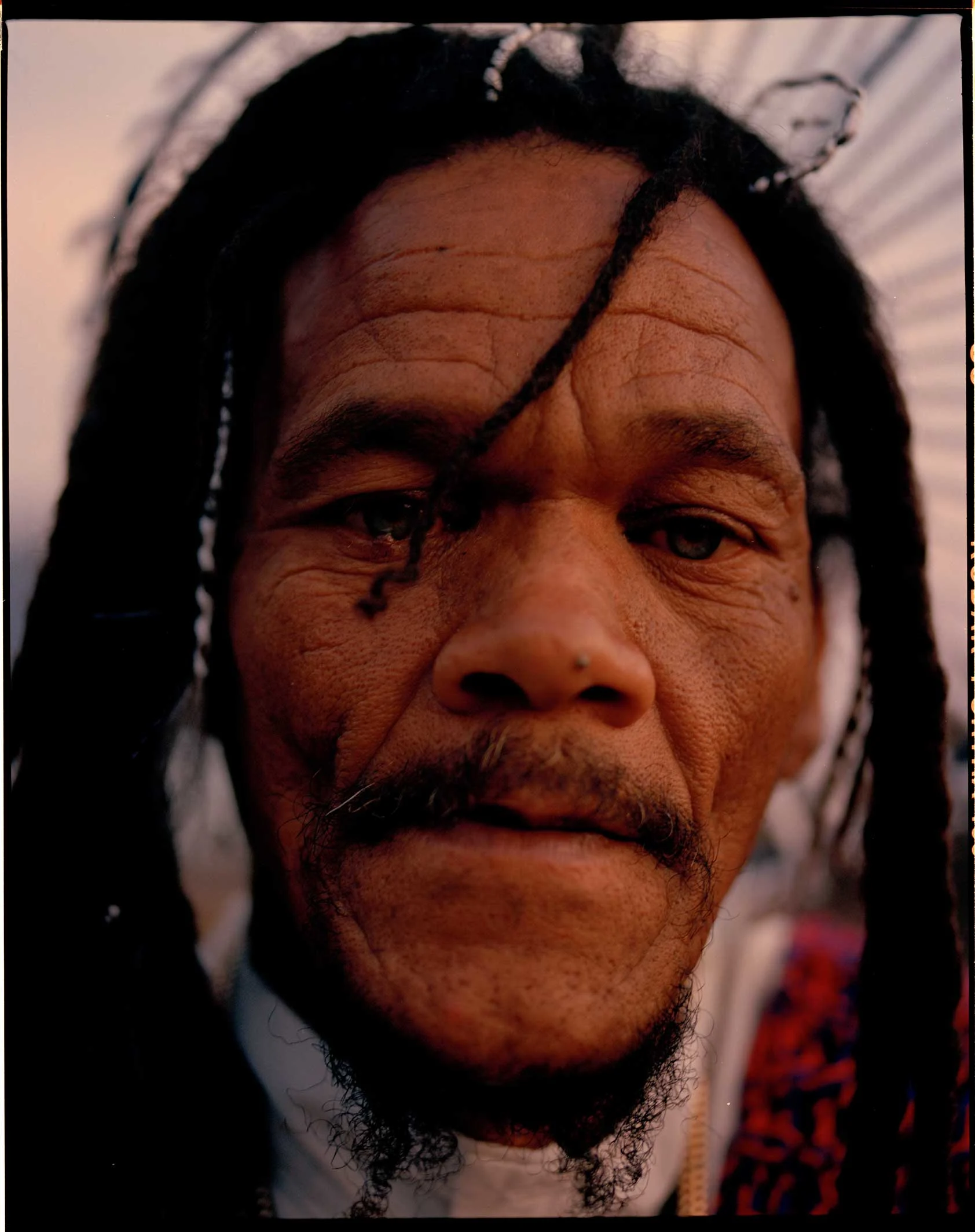

In 2017, South African photographer and artist Imraan Christian launched his ongoing project Ma Se Kinders, as part of an effort to decolonize history by reimagining the past and the future through stories. The name translates to “mother’s children,” and began as a series of striking portraits, taken in the fishing community of Hangberg, Hout Bay, in which subjects take on mythical characteristics. It has since grown into a media entity in its own right, providing skills training that enables members of the community to add to these stories themselves. There are creative workshops in photography, film, dance, and martial arts, and the Ma Se Kinders crew has been commissioned to produce TV commercials and short films for Netflix, as well as campaigns and educational drives.

Through his Ma Se Kinders images, Imraan attempts to channel thousands of years’ worth of rich history into fantastical visual stories that show a different side to Cape Town’s indigenous communities, many of which have unjustly become known for violence and crime.

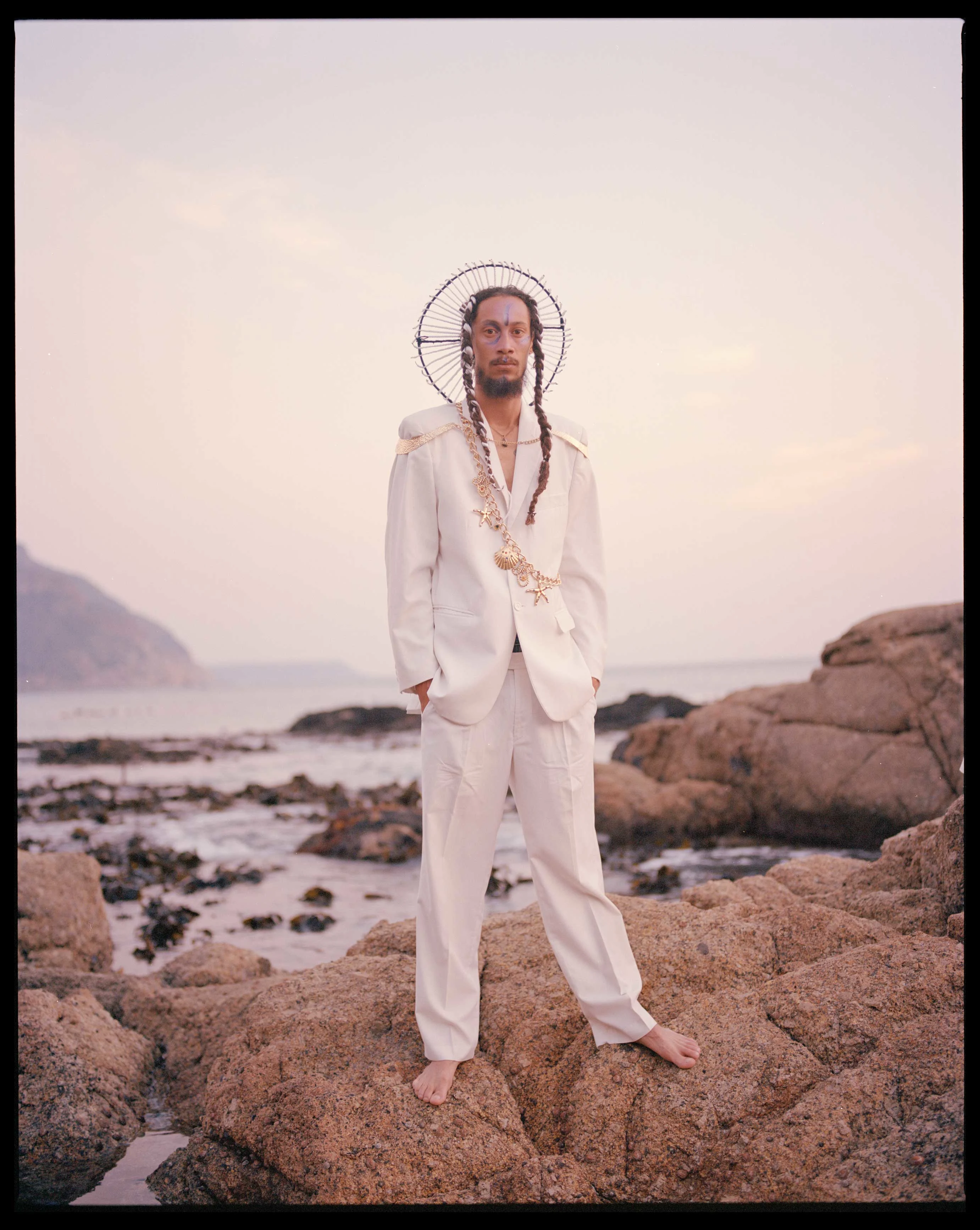

“I wanted to show my home the way I see it: magical,” Imraan says. “It was about paying homage to the good in these neighborhoods. Physically this is the mothers in the community and metaphysically it’s the energy of creation, which is feminine.” Ma Se Kinders has grown into a cosmic anthology of stories, and Imraan describes the latest series Ruh as “one of the constellations within its universe.” In Ruh, Imraan explores ocean mythologies and the archetype of the ocean-dwelling deities and kings through an African lens.

“When people think of the gods of the sea they often think of Poseidon,” Imraan says, but with the characters in Ruh he “flips ordinary convention on its head so that young people within Africa can think of their own imagined mythologies rather than immediately conjuring up images of Greco-Roman gods or Poseidon.”

The characters in the images include a rain queen, dressed in red and teaching her daughter the stories of the cosmos and its relationship with the ocean. In another image is a warrior dressed in white, his long hair representing his memories and the deep roots of his ancestors. In a third the smiling face of a trickster god dressed in blue and gold, who created mankind from nothing.

Hangberg is a powerful place for these stories. The shoreline was one of the first landing places of the Dutch colonists, and the area and its community represent the many coastal settlements around the world that were ravaged by imperial forces landing there. “Where we find historical loss,” Imraan says, “the only thing we can do is draw from our culture to reimagine and recreate. Then we can transcend that vast chasm of a destroyed history.”

At the core of Imraan’s work is an attempt to show the universal nature of all people, but this means a necessary unraveling of ideas of race and color. “We have to go back to go forwards,” says Imraan, and explains that as an artist he is trying to understand what it means to be identified “as a so-called ‘Coloured’ person” since the 1950s and heal the hurt caused in the recent past.

“The zeitgeist around our identity politics here [in South Africa] has been so fucked since 1950,” explains Imraan. “It’s very confusing. So that’s why approaching history through archetypes is so helpful. Our roots are much deeper than 1950 and the four hundred years of colonialism. But you are so hurt by these periods, and they’re so easy to get stuck in, that you can’t see your own truth and the greatness of your roots.”9Under the 1950s Group Areas Act, cities and towns in South Africa were organized into zones that were to be inhabited only by specific races, and thousands of people were forcibly removed from areas that were classified for white occupation. The word “coloured” was officially defined by the South African apartheid government in 1950, partly to facilitate this process. The nuanced histories, identities, and cultures of the people it grouped together were lost to this single, vague category. Since 1950, decades of persecution, poverty, and unemployment have led to these communities having reputations for violence and crime.

Under the 1950s Group Areas Act, cities and towns in South Africa were organized into zones that were to be inhabited only by specific races, and thousands of people were forcibly removed from areas that were classified for white occupation. The word “coloured” was officially defined by the South African apartheid government in 1950, partly to facilitate this process. The nuanced histories, identities, and cultures of the people it grouped together were lost to this single, vague category. Since 1950, decades of persecution, poverty, and unemployment have led to these communities having reputations for violence and crime.

In contemporary South African culture the word “coloured” has become synonymous with gangs and representations in pop culture and comedy often feed into this cliche. “I was raised to be proud of the word ‘coloured’, because I was raised to be proud of my people,” he explains. “But I didn’t understand the limitations of it. The identity is poison. There is a limitation embedded in the essence of an identity that is meant to keep you from dreaming further than a certain level. My people are damn excellent, but mediocrity has kind of become our boundary. We need a mental shift to understand that we can be excellent at anything we put our minds to.”

Imraan started referring to himself as a “son of the soil” and switched to using the word indigenous to describe his people. “We aren’t called by our real names. We’re called ‘coloured.’ But instead of focusing on the wound, I’m trying to understand what the balm is,” he says. “The healing is in the discovery of true history, and the best way to express that is mythology, because it’s not denotative—it’s imaginative. I’m hoping that through imagining our mythologies our people can imagine their potential differently.”

Ruh references the stories of the waters around South Africa. Cape Town has a particularly interesting geography: the history of the city is influenced by the spice trade and its routes. Ships moving between India or Indonesia and the Americas would stop to refuel in Cape Town’s harbors and though the oceans connected the east and the west, they were also the main channel for slavery and colonialism. Imraan’s images, he says, are partially an attempt to soothe the traumatic histories of those who were carried far from their homes over the sea.

A surfer and lover of the sea himself, Imraan explains that working with oceanic mythologies felt inevitable. “I took one step towards the story, and the story took five steps towards me. When I exhale, the story inhales. It’s very humbling,” he says. “I’m just walking my path and focusing on being honest.”

There is another Arabic word that Imraan uses often when he talks about his journey: maktub—it means “it was written.” “The path hasn’t necessarily been easy. It’s perceived as glamorous, but behind the curtain it’s a lot. Dealing with hundreds of years of collective consciousness shit, there’s light and shadow in that,” he says. “So that surrender, that sense of maktub, has helped me accept the journey.”

Ruh isn’t about any one specific tale, it’s about opening the possibility to reclaim identity through the creation of myths that indigenous people can recognize themselves in. The characters are there to help the viewer imagine meanings of their own. “Creation is a divine process,” Imraan says. “Through expressing yourself you heal yourself because you’re in conversation with the spirit.”

Photography / creative direction: Imraan Christian, Production management: Fidel meter, Peter Michaels, Production co ordination: Haneem Christian, Waseem noordien, Styling: chadlee van wyk of Forge Studios, Hair: Kelvin Takudzwa, Make up: Michelle Lee Collins

Cast: Khanyisile Masina, Sabre Arendse, Papa Grimm, Adolf Ndlovu, Tylo da Silva and Gary Louw.