Reclaiming spaces and pushing the boundaries of artistic experience has always been at the heart of artist Doug Aitken’s practice, whether that is installing work in the desert or submerging sculptures underwater. His latest project though, turned skyward. Here writer Elliot Watson meets the artist to find out how to disconnect from the de-material world, and why it’s time for a return to the real.

Photography by Rachel Cabitt.

“So we take off and we’re flying over the landscape; flying over marshes, flying over forests. It comes time to land and we look down to see barbed wire fences and armed pavilions. Then we see the police cars following us…” On 17th July Doug Aitken and his pilot were confronted by police. The artist’s latest project - a 100ft reflective hot air balloon called New Horizon - had drifted into and landed in the vicinity of a maximum security penitentiary. Law enforcement were conducting their due diligence to establish that it wasn’t the most aesthetically inclined contraband drop or prison break in history. It wasn’t, of course.

With its dramatic local news tone and once-in-a-career storytelling cachet for the attending officers, this anecdote is strikingly apposite for the New Horizon project at large, of which the balloon was the enigmatic centerpiece.

“In a world where things are so homogenized and we associate art with seeing it inside architecture and inside a gallery or a museum, a project like this is in a very different direction,” says Doug of the personal attraction to, and egalitarian necessity of placing art where people can actually see it - one hundred and fifty or so feet into the blue sky of New England, for example.

Constructed from Mylar - a high strength silver film originally developed in the 1950s to record reconnaissance missions conducted by high-altitude aircraft - New Horizon is a mercurial sculpture. It’s “like a melting Brancusi” as it’s being inflated or deflated, and like a translucent globe when it’s airborne and reflecting its surroundings. It has Victorian proportions and a NASA aesthetic.

It is a spontaneous sculpture too, subject to the elements - wind especially - and to the expertise of its pilot and the mood of the Federal Aviation Administration, who decide what can fly, when and where in American skies. “The project is completely in flux all the time. You’re part of a natural system - part of the wind, the sun and the rain and the moon. It exists in a space that is intensely physical,” says Doug, describing the project’s powerlessness against the elements though not mentioning the potential for bureaucratic intervention.

Throughout July New Horizon toured Massachusetts, stopping at a series of locations maintained by The Trustees, an organisation that preserves over 100 historic properties and places of natural beauty statewide. Between scheduled stops the balloon took impromptu, weather-permitted flights, announcing itself to bewildered farmers, jazzing up the mornings of gridlocked commuters and offering a shimmering reflection of every landscape it sailed above. For the artist, the project’s encounters with passive observers were some of its most important: “Why can’t an artwork penetrate the landscape or ambush one and be something to discover?, he asks. “Does Costco ask our permission to roll out a huge parking lot, or the Days Inn to make another motel?”

The answer of course is that yes, art can assert itself upon a landscape. And New Horizon is not the first of Aitken’s works to do so. His 2015 project Station to Station involved a train crossing America from coast to coast as a rotating ensemble of artists (including Patti Smith, Beck, Ed Ruscha and Giorgio Moroder) climbed aboard and took part in events across ten locations from major cities to backcountry gathering spots. The project was billed as an artistic re-imagining of the great American road trip, a kinetic sculpture that harnessed the creativity of icons whilst completing a storied, mythological coast to coast journey.

Mirage (2017- present), meanwhile, featured a Frank Lloyd-Wright inspired California Ranch style home composed of reflective surfaces installed in the Palm Springs desert, then in a former Detroit Bank building and most recently in the Swiss Alps. In many ways, it’s a less mobile predecessor to New Horizon that shares its chameleonic ability to disappear into its environment. The less accessible but truly bold Underwater Pavilions (2016) created with Parley for the Oceans, featured three sculptures submerged off the coast of California’s Catalina Island, around 30 miles from Los Angeles.

Like the land art of Walter de Maria or Nancy Holt, the beauty of projects like New Horizon, Mirage and Station to Station is that they are a non-commercial presence in the landscape, a rejection of the billboard and promotional blimp culture that has become the status quo - something that Doug feels is an important quality for art in a world where every inch of land or sky is liable to being co-opted by corporations. “When you have an artwork that can be discovered by happenstance, by randomness, you suddenly have this idea that everything is possible and the entire landscape is a metaphorical canvas to be used in a creative way.” He explains, “To me that is a revolutionary act, reclaiming that space from capitalism.

“It’s an act of saying, ‘yes I could be in the same motel room in that same motel chain that goes across America, eating the same food at the same chain restaurant. But what happens when I deviate from that?’” Looking into the sky at New Horizon, it appears to be a good case in point - an emphatic departure from a night at the Days Inn and a cheeseburger at Chili’s. It’s giant, airborne and bearing no slogan or logo.

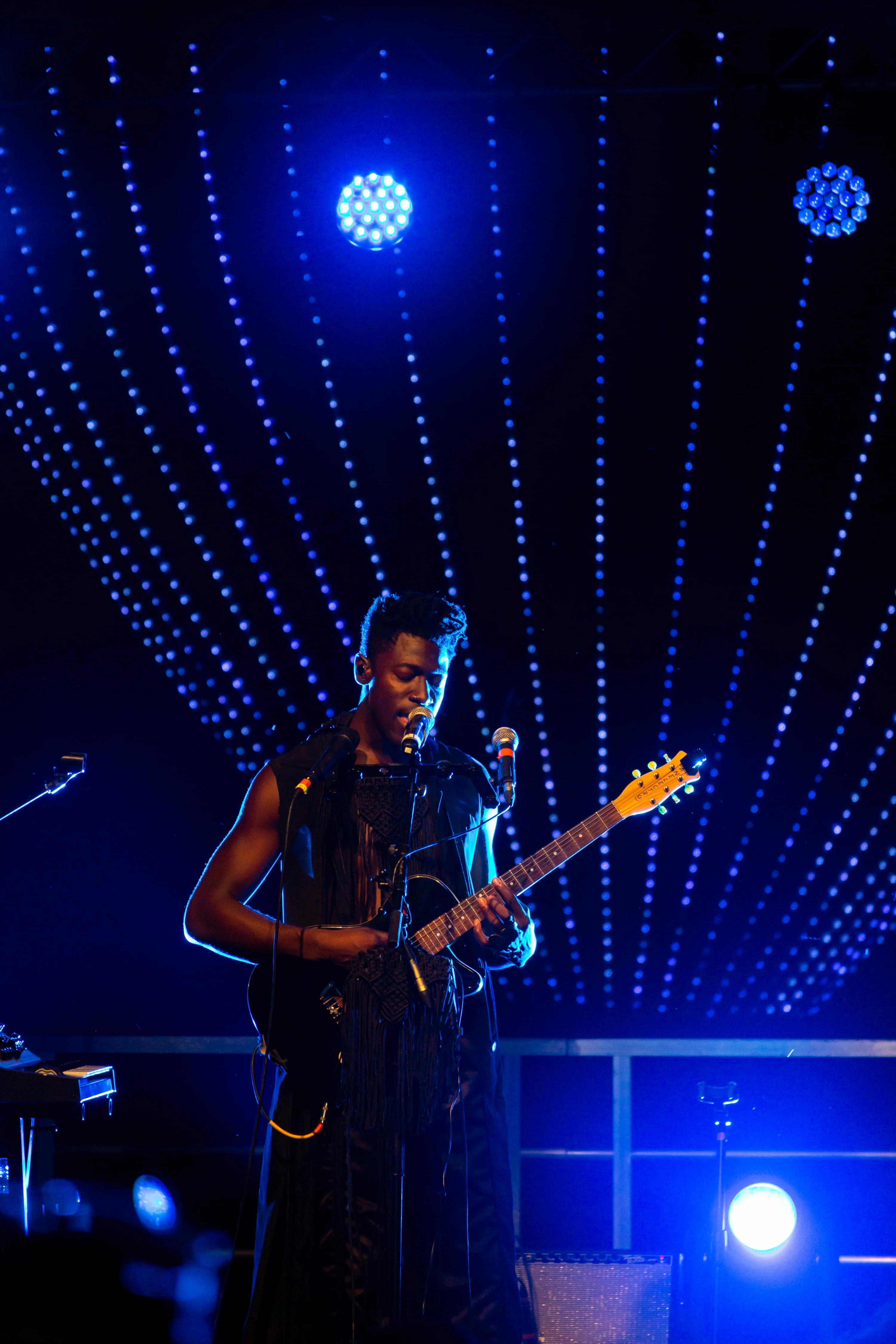

Much like with Station to Station, at each of New Horizon’s four scheduled stops ticket holders were able to attend “happenings” consisting of topical discussions (on the nature of identity in the digital age or the notion of applying creative minds in search of humanistic solutions to global problems, for example) and performances by a selection of progressive musicians including Mac Demarco and Moses Sumney. A light show emanating from the balloon acted as a backdrop for the concerts. The events were curated by Aitken, continuing his form of using his installations to pass the mic and to stimulate discussion and creativity through cross-cultural collaboration.

Experienced in its totality, New Horizon is a temporal, physical, collective experience of great contrast to the archetypal 2019 existence in which we are doomed to spend (as an American adult, according to MIT) an average of around 24 hours a week online, exchanging or consuming two dimensional images, text or video through a screen, locked in a space that Doug calls the “de-material world”.

It’s not that the project is intended as a condemnation of the post-internet era, but more like an opportunity to provide a complementary experience that has become more scarcely available. “We’re in the first chapter in the 21st century and I believe we desire experience and we desire to author and seek out something,” Doug says, “There is a great value for that to happen in the physical world and to find new ways to activate or create a bridge between the tangible, tactile world and the de-material world. Much of our life is lived in this pendulum somewhere in between.”

Doug sees his practice of creating in-the-moment artworks as part of a broader sociological trend of valuing experience over objects, a preference that has been predominantly attributed to younger generations navigating their online versus IRL existence whilst subconsciously disenchanted with the material-forward capitalist dream. “As our society accelerates and images flatten, we desire to touch and feel the earth and to connect ourselves to the physicality of the natural world,” he says.

“It speaks to that idea of reclaiming reality, saying to ourselves that it’s not enough to be passive and to be fed the politics and the consumerism that we are,” he continues, “but it’s okay for us to go and author our future – we can claim our own reality and we can write it. It’s almost something you could call ‘a return to the real.’”

A few days after the police encounter, Doug is taking shelter in a manicured hedge at The Crane Estate, the grounds of a 1920s Stewart-style manor house close to Ipswich, Mass. A torrential downpour has temporarily grounded New Horizon and interrupted the event’s program of speakers and musicians. Many of the locals remained stoically assembled on their picnic blankets, barely shuffling to put on rain jackets.

For Doug, just as when the wind pushed him towards jail, this intermission is a part of the artistic process, an occupational hazard of creating work that is responsive and alive, a physical, tangible experience. “They tell me this happens in New England,” he says.

Twenty minutes later, proceedings resumed.