Ghent-based painter Bahati Simoens grew up adoring the work of Hockney, Gauguin and Rousseau, but later in life pivoted to the work of Black artists for inspiration. Allyssia Alleyne speaks to Bahati about her work, and the effect her childhood, family holidays and her mother’s heritage have had on the paintings she creates.

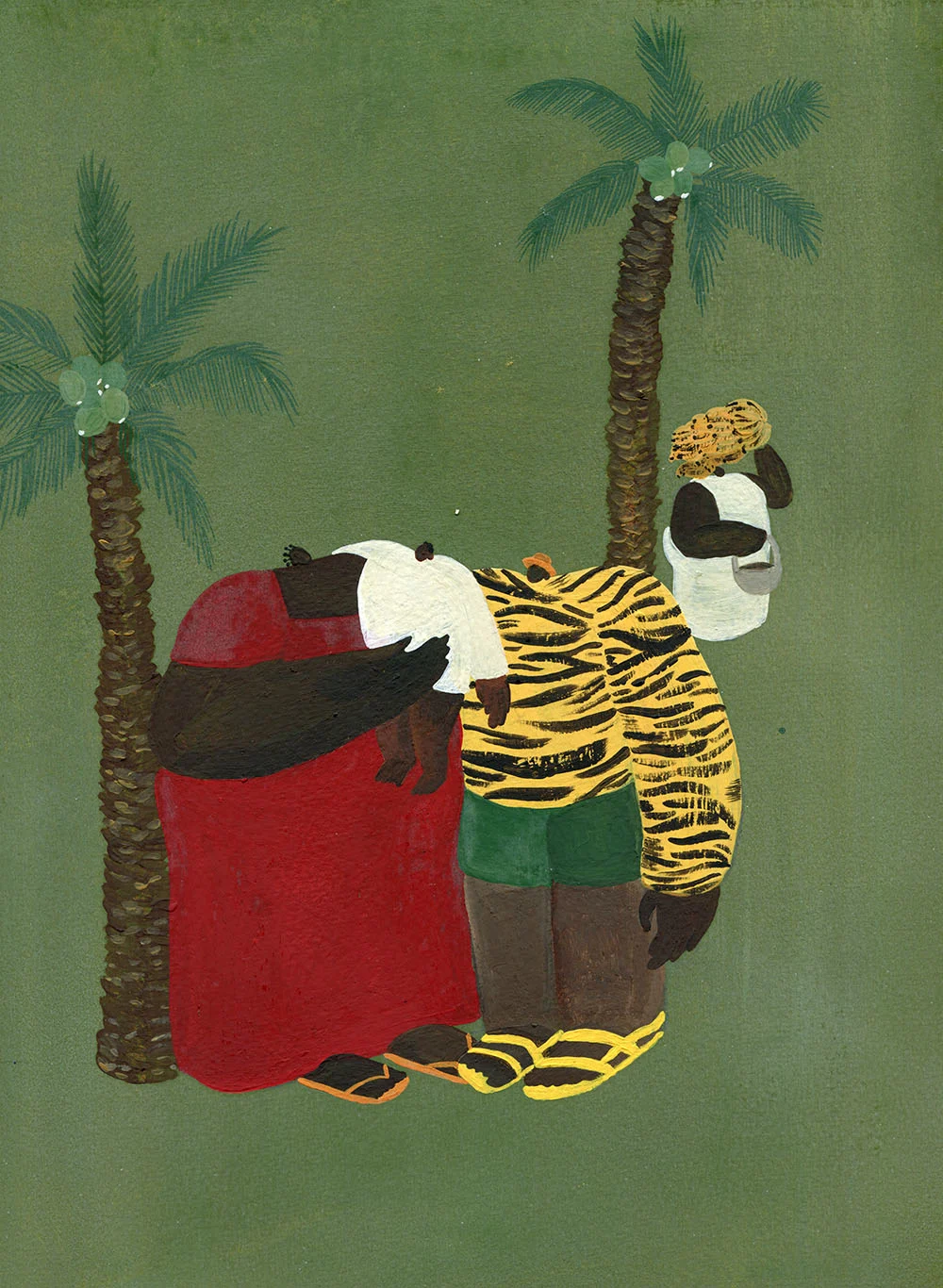

Bahati Simoens isn’t quite sure what first drew her to paint her oversized, faceless figures, but at this point, she’s stopped questioning it. They’ve become a signature of hers, these round bodies, with fleshy arms, stomachs and thighs in shades of brown, topped off with tiny heads and tinier hats, earrings and hairstyles. They’re painted onto flat colored backgrounds, or inserted into calming scenes that remind her of home, of her childhood in Burundi, of her mother’s stories of her life in the Congo. Couples embrace, children are held, food is prepared, meals are shared, all in clean, bright strokes of acrylic.

“I really loved the work of Paul Gauguin, David Hockney, Henri Rousseau, and their use of very bright colors… But now I go more into Black artists I find online, or just childhood memories or pictures as a form of inspiration,” Bahati explains, pointing to the work of current favorites like Cassi Namoda and Wonder Buhle Mbambo, recommending Instagram feeds to follow, newly opened exhibitions to visit.

Speaking over the phone from her home in Ghent, Belgium, the 27-year-old is delicate in tone and considered in speech. “I'm pretty soft as a person, as well. Very calm, I have a lot of patience,” she says. “I’m a true capricorn: I act all tough, though I’m super sensitive. It’s very seldom that I go into my emotions and openly express them.”

But her work is one place she’s happy to open up about her feelings about racism, love, diaspora and home. This year in particular, a sense of conflict has seeped into her paintings, communicated through subtle details. A man sits slouched in a tropical scene, his sweater shouting FYPD (Fuck Your Police Department); tattoos on a full belly declare “ENOUGH IS ENOUGH” and “Black since Birth”; a woman wears the face of Breonna Taylor on the front of her dress. In a more overtly political painting, a family carries a lifeless body on the lawn of the White House.

Bahati sees her use of colour and general softness as a form of disarmament, luring in viewers so that she can communicate serious themes. “I think if you want to make people aware of something, it doesn't work when you're filled with anger and pain and disappointment, and you're being very loud about it,” she reasons. “It helps when you try to make a point in a soft way.”

Before she turned to art as a way of communicating with others, Bahati says she saw painting as a way to connect with herself. Both of her parents – her father, a Belgian math teacher and her mother, a much-younger Congolese woman he met while working overseas – were artistic and encouraged her talents from a young age. She remembers growing up surrounded by her mother’s drawings of birds and landscapes, and her father’s abstract paintings and photographs of his time in Africa. “I feel like I had a very cultured upbringing,” she says. “But also very strict.”

After her parents’ divorce when she was eight, Bahati and her siblings were primarily raised by their father in the city Ostend on the Belgian coast, where she felt choked by the lack of diversity, dissected by the white gaze, and restricted by her father’s rules. “My father is pretty old-fashioned and he's a Christian, so it was no boyfriend until I was 18, no going out, no sleepovers, no watching MTV when he was around,” she recalls, laughing.

While her mother taught her to cook traditional recipes and regaled her with stories about her upbringing, she never felt the need to discuss issues of race with Bahati and her siblings, though she herself a victim of systemic racism: “She was like, ‘You guys are European now.’”

At 17, Bahati moved to Ghent, which was more racially diverse, to escape this feeling of not belonging. After a short and demoralizing stint at art school, where she felt stereotyped by her instructors and intimidated by the predominantly white student body, things began to progress. She started dating her first boyfriend, a Black man who exposed her to African-American culture; and, working at a coffee shop staffed by aspiring artists, she developed a diverse group of friends with whom she felt she could be herself and “go deeper” into her identity.

Her first relationship, however, was followed by a second, with a white boyfriend who was dismissive when she brought up the racist comments and actions from people within his circle. “It definitely messed up all my chakras…I felt like a teenager again – afraid to speak up, constantly going over my sentences in my head not to step on all these white fragile toes around me,” she says. “But during those silent years, I gained a lot of wisdom from being so quiet and observant.”

A second turning point came during a month-long trip to South Africa in 2017, where she felt herself blending in for the first time since childhood. “My soul feels more present and at ease around Black people,” she says. “Being in a kind and loving environment, blending in, surrounded by people who are like me – but also seeing the after-effects of apartheid – I became aware about the importance of speaking up.”

Upon her return to Belgium, she says, “I remember having this burning desire to go back into my art. Recharging and refreshing my mind in places like that is a must to me, as an artist, but as a whole being as well…I started speaking up to my boyfriend on , their microaggressions and injustice at large, which he couldn’t handle, so that was that.”

From that point, she says, painting became a form of therapy. While her original paintings were tiny works on paper populated with tiny figures, she says they grew bigger as she became more confident and started to paint on canvas.

In her artworks, in her Instagram captions and in life, she says she’s now unconcerned with the weight of white gaze or the sensitivities of white spectators. Instead, she’s focusing on creating work that Black people will be able to see themselves and their experiences reflected in.

“I am my mother’s daughter, a Black woman and proud,” she says. “I’d still love everybody to enjoy my work, but I mostly want to hold up the mirror to make Black people feel seen, while still being aware of the hurt and the pain – in a soft way.”