For 22 years, 15 Rwandan women have been turning their surroundings and their memories into beautiful textile art. Founded in 1997 by Christiane Rwagatare a short time after the genocide of 1994, the Savane Rutongo-Kabuye workshop offered a distraction, a source of income and a creative avenue to those who had been affected. The workshop has gone from strength to strength, and thanks to educator-turned-curator Juliana Meehan, the embroideries of the women of Rwanda have now been exhibited and seen across the US. Alex Kahl spoke to Christiane and Juliana to explore their uplifting story.

Due to her home country Rwanda’s turbulent history, Christiane Rwagatare lived much of her early life in exile. When she returned in 1994 in the aftermath of the genocide, the country had been devastated. “It was a very difficult time,” she says. In 1997, when she was visiting a relative in the small village of Rutongo, she saw women selling hand embroidered linens on the roadside, and felt an immediate sense of hope and possibility. At this moment, she recalled all that she had learned about art while in Europe, and knew she could contribute something positive. She announced that she would be starting an embroidery workshop, and asked that anyone interested come to the village church the next day. She was shocked when more than 100 women arrived with samples of their work.

“I must admit that I panicked,” Christiane says. “I had to explain to them that I could not afford to supervise all of them, since my income was limited and the room I planned to rent from the priests wasn’t big enough.” She was forced to pick the 15 women she could see had the most talent, and in that moment the Savane Rutongo-Kabuye workshop was born.

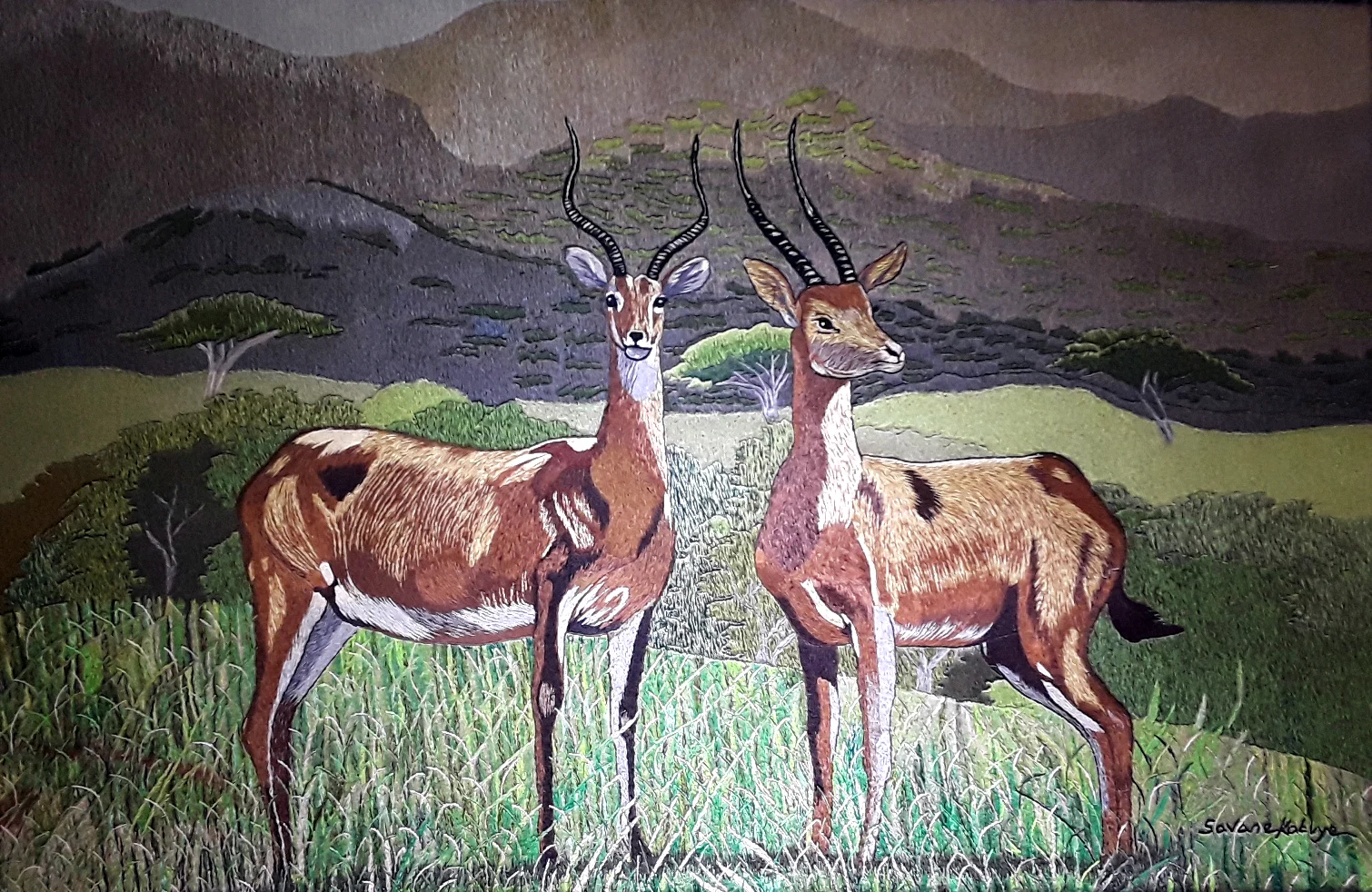

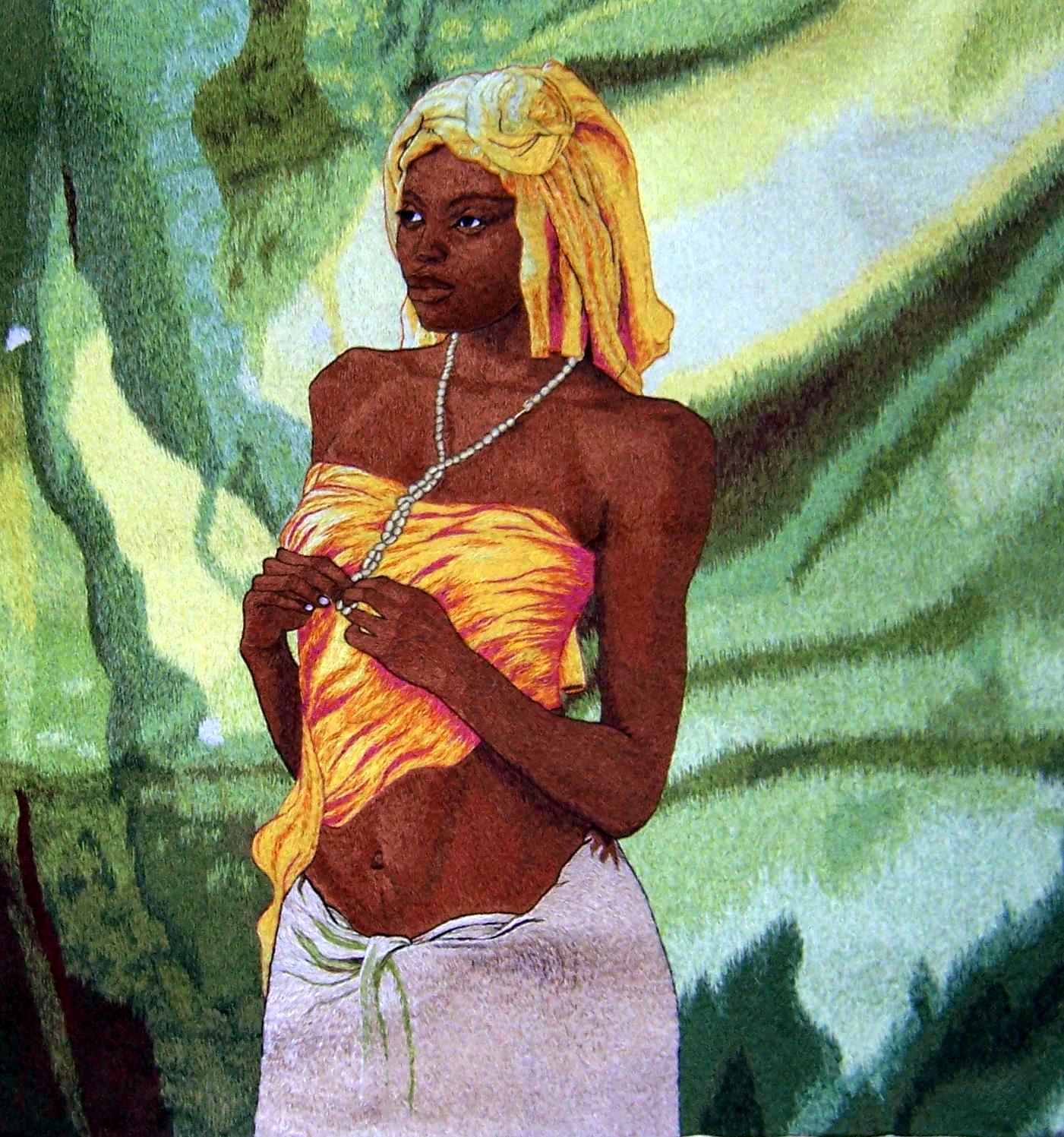

The women of Kabuye work together to create each piece, each one a colorful depiction of a scene from their surroundings. Christiane or her niece will first make a sketch on paper, and then will transfer this sketch onto canvas, adding details. Threads will be picked that correspond with the colors needed for each scene, and then the embroiderers will begin their work. They use three different colors of thread on each needle, “mixing thread as a painter mixes paint,” which allows them to create a level of depth and detail that does the vibrant scenes justice.

Potential scenes are selected by all the women involved, whatever comes to mind, from aspects of Rwandan culture and things they see on a daily basis to images buried in their memories. “The process of creating a piece is first to draw inspiration from our environment, from village scenes, landscapes, animals,” Christiane says. Antelopes stand majestically before hills and forests looking off into the distance, lions stare straight out at the viewer as they would at their prey. Animated drummers play and villagers dance, and various people are captured in solo portraits, their personalities brought to the fore by the embroiderers. The works are at their most captivating when the landscape is shown in all its glory, from sprawling green plains to shimmering lakes and beautiful orange sunsets.

The embroideries of the women of Kabuye remained relatively unknown outside of the local area until a chance visit from Juliana Meehan, an educator from the US. She walked into the shop as a tourist and fell in love with every piece of work, buying all but one of them on the spot. Christiane invited Juliana and her husband to come to the workshop and see up close how the work was made. “There, in a small house of whitewashed cinder block, 15 women sat with cloth spread across their laps, patiently, expertly creating vibrant embroideries like those I had just bought,” says Juliana.

As she prepared to return home, she asked Christiane if there was anything more she could do to help her cause. Christiane admitted that the ultimate goal for her would be to have a show in the US. “I returned home with a mission,” Juliana says. “To support their efforts by bringing these works to the attention of the American public. I knew people would love them as I did.”

Since then, the works have been shown at exhibitions throughout the Northeast U, in Washington DC, New Jersey, New York and Ohio. Juliana named the series of exhibitions PAX Rwanda, meaning Rwandan Peace. The use of the word peace is a reflection on how the workshop helped the local villages through a difficult time for the country in general, and how it connected women from both sides of the troubles. Christiane’s bravery and determination gave these women work, a distraction from the events of 1994, and just as importantly gave them an income with which to support their families.

When Juliana returned to Rwanda recently, she interviewed each of the women working in the workshop to learn more about their stories. “Even 22 years post-genocide, it was immediately clear that no one’s life is untouched by those 100 days in the spring of 1994, when almost one million Rwandans were killed,” she says. “It left ten times more widows than widowers.” Many of the women lost children or husbands, but the workshop gave them something to focus their minds on.

Most of the women were taught the art of embroidery by Belgian missionary nuns in the 1980s, and then went on to their various careers, but all work stopped when the genocide occurred. Christiane’s workshop gives the women a chance to once again use these skills and express themselves creatively. Some live far from the workshop, travelling for hours to come and work with the threads. Others speak of the artistic freedom it offers them. Some are just happy to be able to give their children more opportunities. For all the various things Savane Rutongo-Kabuye means to them, it’s the place where they can come together. “It's been 22 years since we started, and we’ve always managed to work in conviviality,” says Christiane.

When Juliana suggested that the works should have some sort of signifier of the artist, the women rejected including individual names, instead choosing to sign each work as a group with the name of the workshop. “When it comes to signing the work collectively, it’s because it’s such a collaborative process,” says Christiane. The choice not to include their own names and the rejection of individual plaudits speaks to the strength of the bond and to the sense of community that has been built over these two decades.

Juliana has often noticed that many Western people think of Rwanda and only see the genocide and the problems the country has faced since. These embroideries, though, show the everyday intricacies of the country from the perspective of those who have called it home their whole lives. “The actual traveler to Rwanda comes away with something much more complex and beautiful,” she says. “All these things are inextricably interwoven in this country known as 'The Land of a Thousand Hills.'”