Growing up, illustrator Nina Torr had a dog called Camilla with a very expressive face. Nina believed her furry friend was capable of showing human emotions. Now, Camilla’s expressions have found their way into each animal the South African artist draws. In fact, they take the lead role.

“Animals are more symbolic than people, so there’s a lot more storytelling potential,” Nina says. “Also, they don’t speak the same language as us, so they often get frustrated at not being able to communicate with us properly – or at least Camilla did.”

The world in Nina’s paintings is potent, mystical and mythological. Moon-faced or masked figures draped in colorful cloaks drift amidst her animals. She looks to Medieval art for inspiration and as a result, the creatures in her work tend to be weirder and more wonderful than you can imagine.

If you'd like to see quite how odd Medieval animals can be, we direct your attention to Buzzfeed, and 44 Medieval beasts that cannot even handle it right now.

Although artists from the Middle Ages were skilled, they didn’t have the more advanced understanding of science, anatomy and physics that came later during the Renaissance. “So, there’s a more exploratory and naïve sense of problem-solving,” Nina says. “It’s not always correct, but in a way, it's more honest and active.

“The vanishing points tend to be all over the place and the compositions become quite vertical. Artists would often use scale in a hierarchical sense rather than to define depth. The most important figures would be depicted larger and the lesser folk would appear small, knee-height even. I love that!”

As far as animals were concerned there were no reference books or Google Images. Artists had to rely on what they were told animals looked like, and this wasn't always scientific. “Imagine if you’ve only heard descriptions of whales," Nina says. "Think about how terrifying they must sound. Combine that with mythology and storytelling and you’ll soon end up with some very strange-looking animals. I like the idea of filling your gaps in knowledge with imagination.”

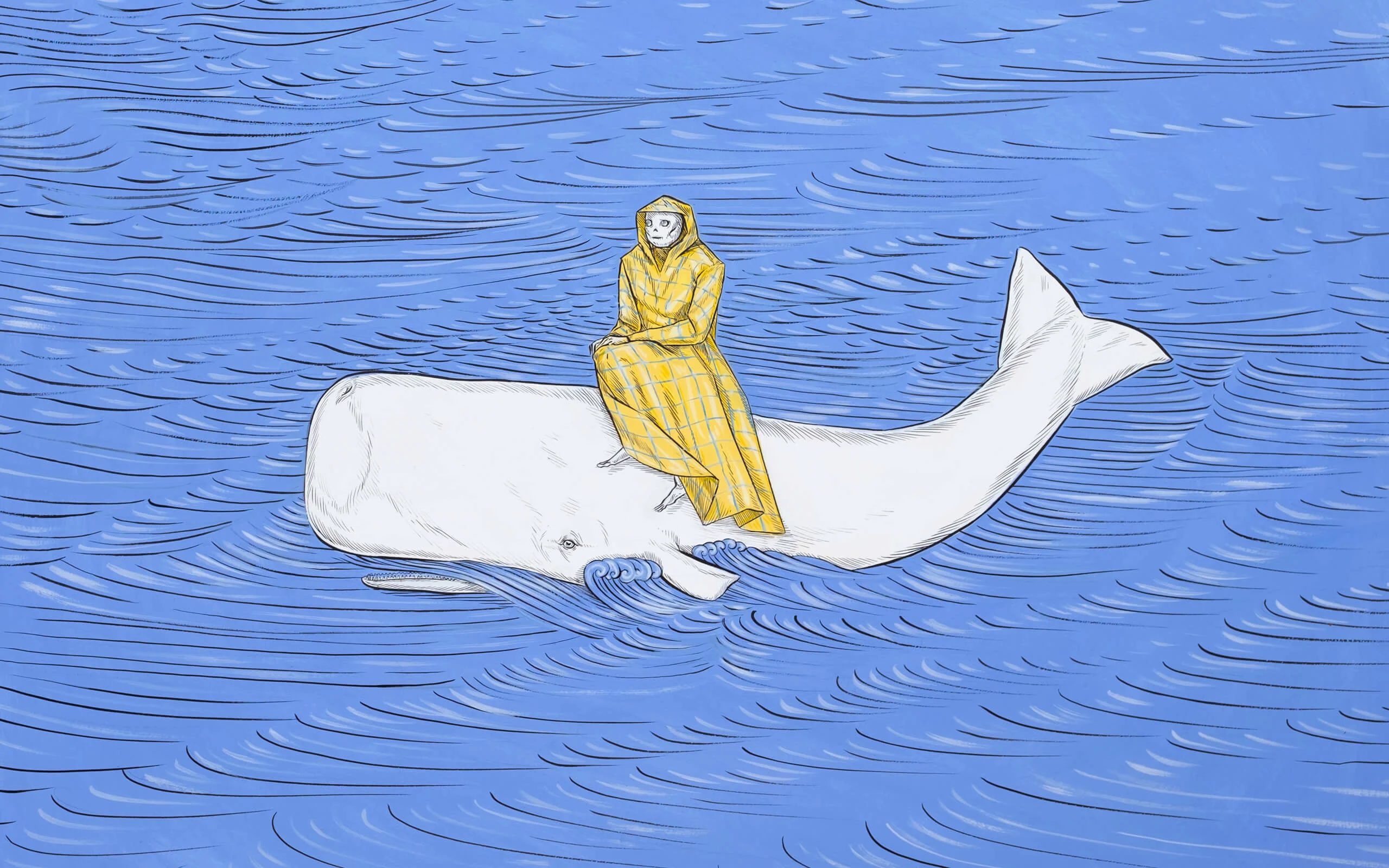

Nina tries to embed this idea into her own work, with (literally) fantastic results. But it’s not just her animals – her moons have facial features and her suns shed tears. There are skeletons riding whales and tigers eating the sun.

“There’s a tendency in Medieval illustrations to put faces on everything,” she says, “which I find amusing. You can even find illustrations of vegetables with faces.”

But the faces serve a purpose too – by giving everything a personality no single thing becomes the focal point. “I fear that if I drew actual people, I would get too distracted by their personhood, their portraiture. I’m more interested in their expressions and gestures, so I transfer those onto something else, like suns, moons, animals or skulls.”

Sometimes when she’s finished a character, she realizes she’s been inspired by someone she knows (only now her friend is a skeleton in a yellow cape sat side-saddle on a whale in a wind-whipped sea).

Speckled backgrounds add texture to Nina’s visuals, which she creates with an interesting choice of brush. “I found this great Colgate toothbrush,” she says. “It’s got a black and pink handle and black bristles. It’s meant for very sensitive teeth, so the bristles are super soft. It works very well for the fine speckles.”

For larger speckles, like in her starry night skies, she flicks paint off a paintbrush, and for gradients she uses spray paint.

Although she uses a language of symbols, Nina says there’s no code to crack. “I’m just trying my best to approximate a thought I can’t quite put my finger on.”

She’s exploring this concept further through her Masters dissertation and has come upon the term “tacit knowledge” – knowledge that is implied or felt but difficult to explain through words. Her art is an attempt at relaying this untranslatable thought through imagery.

“It comes from an unconscious place,” she says. “Mythology, religion and folklore all arise like this. It’s not consciously constructed; it just manifests. You imitate what you see around you and then slowly develop your own version by keeping at it.”

Words by Alix-Rose Cowie.