Fleet Foxes’ success can be attributed to the unusual team behind it: the Pecknold family. While Robin is the bandleader, his older brother Sean takes care of the visuals - having made eight of their music videos already - and their sister Aja is the band’s manager. Together, the trio have been shaping the sound, visuals and story of Fleet Foxes.

The six-piece band, known for their signature vocal harmonies combined with their distinct sound, have been around for over a decade. You might know them from their 2008 self-titled debut album with tracks like White Winter Hymnal or their EP Sun Giant with the soothing Mykonos. After a six-year hiatus, they released Crack-Up in 2017, which Pitchfork called “their most complex and compelling to date.”

Most recently, Sean and his team hauled a 1990s Panavision camera out to the California desert to film the music video for I Am All That I Need / Arroyo Seco / Thumbprint Scar – the first track of the new record. The video, commissioned by WeTransfer, showcases once again the unrivalled creativity that is the Pecknold siblings.

Shot entirely in 35mm film, the camera moves from a wood-paneled house to a blue-tinged rock pyramid to a still lake, mirroring the vacillating tension in the song — the flip from loud to gentle, from sorrow to joy, from the surreal and familiar to the abstract and meteoric. A cigarette butt, a dirt road, a red glass cube.

Below, together with his brother and sister, Sean takes you on a Fleet Foxes retrospective and talks through some of the music videos he’s made for the band over the years. We follow his evolution from animation to live action, and watch as he tries to push his visual language as close to the sound as possible, without trying to interpret his brother’s words too much. First up, White Winter Hymnal.

White Winter Hymnal

Sean: I remember in New York in March, 2008, Robin said, okay brother go make a video. So I had to figure out how to do that. I made these sculpted characters from clay. I did the prototypes, but I didn't know how to make a full-on working puppet.

What little animation there was in that video, there was only two weeks to make the stuff. It was me, Chris Rodgers (a talented animator I found on Craigslist), Paul Maupoux and Britta Johnson, a Seattle stop-motion animator whose work I'd admired. She ended up being the key collaborator on The Shrine and most of my other stop-motion projects – she taught me so much about the craft of making animations this way.

I was so stoked to be making a music video. I was obsessed. I found what I wanted to do.

We stayed up really late for two weeks. The animation was really simple: hands and eyes closing and Casey Wescott headbanging. I just wanted to do the song justice. I was so stoked to be making a music video. I was obsessed. I found what I wanted to do.

Mykonos

Sean: It was the December of 2008, maybe January, and Robin was leaving for tour. I wanted to do another stop-motion because that's what I felt really good about doing – an extension of White Winter Hymnal, but more abstract.

I built a black duvateen cave. I went to Value Village on Capitol Hill, found a little glass end table and stacked it up on books. Jesse Brown, a fantastic Seattle artist, was designing the buildings, so he would come by in the evenings and work on the little structures that were going to be falling apart. The animation and lighting gets progressively better over the course of the video.

I remember biking home at three or 4AM and being totally full of adrenaline and obsessed. I knew I couldn’t just make White Winter Hymnal and then say, see you later and make some bullshit.

Stop-motion animation is gratifyingly linear. If you shoot something for two hours, it’s been shot. You can't change it.

Aja: Biking also has kind of been a through line in your creative process.

Sean: It is. You are not tied to anything, you're moving forward, and your brain's free to reflect in a more positive light. I remember biking home from my studio and just being so stoked. And going back the next day, cutting paper and keeping going.

People love that song so much. It needed something great. If we had done that video out in the world, with the band, it wouldn’t have worked. It ended up really benefiting from this abstract approach. I was able to project onto what it was and still follow something, my own thing.

Aja: The level of patience that you must have while making something like that is pretty remarkable. There's no instant gratification in any way.

Sean: I never thought I had any patience at all. And I didn't really.

I think it’s wrong to dig too deep into the meaning of one person's art, especially when trying to make an accompaniment to it.

Aja: So what makes this different?

Sean: It’s because stop-motion animation is gratifyingly linear. If you shoot something for two hours, it's been shot. You can't change it. It's just one journey forward. You can adjust as you go, but you can't go back. With computer animation at any moment you can go in and tweak the key frames of any particular part. It got to where I learned you can slow your heart rate down. It was cool to find that patience.

Aja: It sounds meditative. Where does your interpretation of what you think the song is intended to be end and your vision of the work begin? Are you able to detach from what you think Robin's point of view is while making the song? Did you struggle with that?

Sean: I think it's wrong to get too literal or dig too deep into the meaning of one person's art, especially when trying to make an accompaniment to it. If I was trying to decode every lyric and every meaning in Robin’s life or what the song was about, I think I would trip up more than if I asked myself: What is this to me? What does the emotional feeling that I get from listening to this song look like?

Robin: Your videos are a second chance to re-contextualize the song. Redefine it. I feel like the White Winter Hymnal video is kind of darker than the song is. The angularity of the Mykonos characters and the shapes are not the first things I think of if I’m trying to make a picture of this song.

The video and the song, they work together. Like Third of May, or Fool's Errand, they allow us to interpret the song in a new way. The videos always surprise me and make me hear the music differently. I get to see how and what the songs move you to make.

The Shrine / An Argument

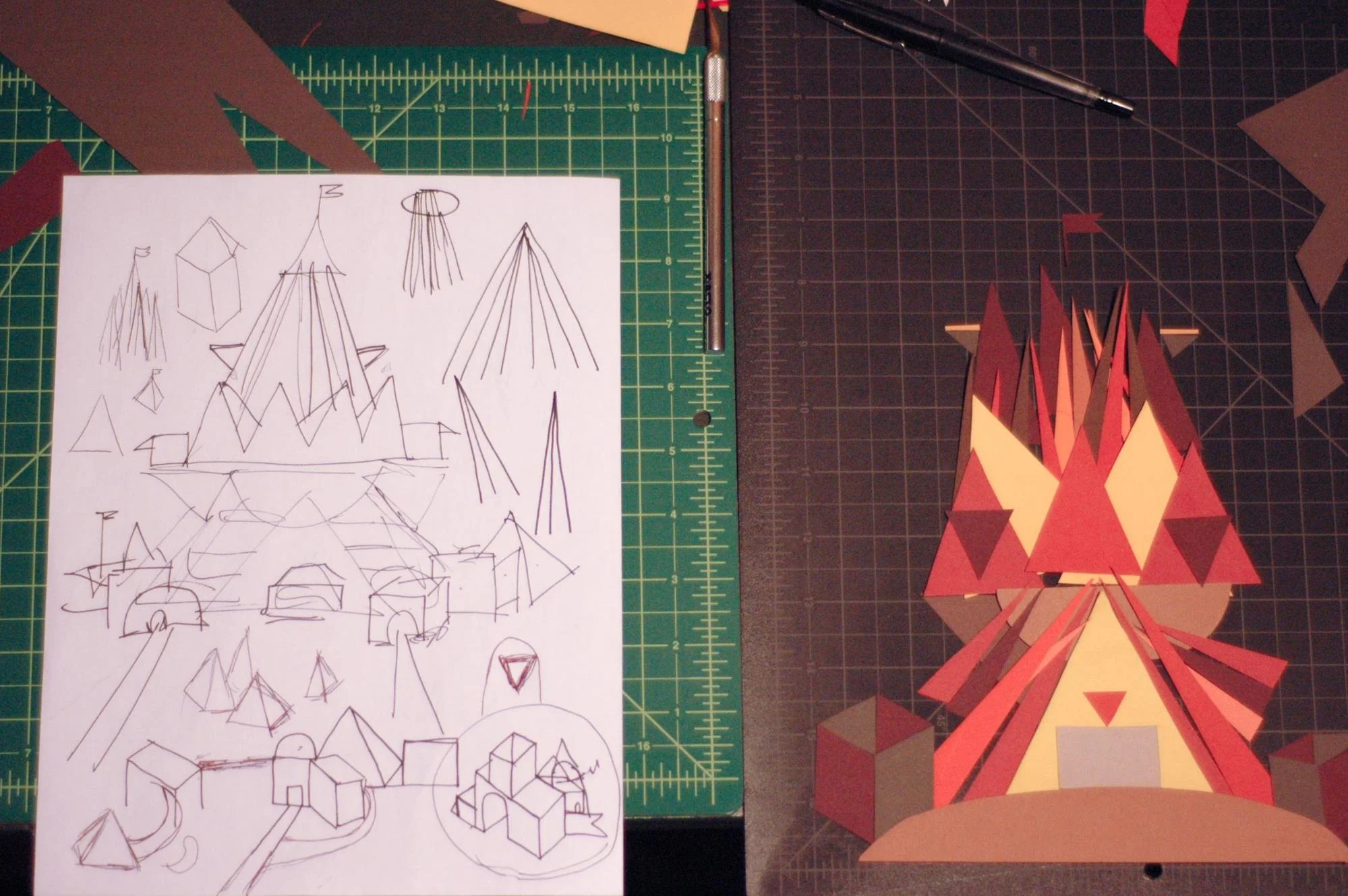

Sean: Robin and I are both fans of Stacey Rozich’s illustrations and we wondered if we could make a multiplane animation for The Shrine. It’s the longest song on the record so it was always the one we talked about doing.

I knew the video was going to take a long time, like five months. I was stoked to dig really deep into a project. I became obsessed with Yuri Norstein’s Hedgehog in the Fog. He’d make epic animations over ten year periods and was using the same kind of table we were. His version was enormous and he had rollers where he would roll backgrounds in place, left to right.

Our dad Greg Pecknold figured out how to build our own multiplane table out of Speedrail, and we moved it down to Portland for the shoot. I still use it today.

Another filmmaker, Lotte Reiniger is an German silhouette, paper-cut animator whose work I knew and loved. Her table was fairly simple but she made a few feature films and a bunch of short ones. Incredibly prolific.

Also, this Italian film called Allegro Non Troppo which was sort of a take on Fantasia, but kind of psychedelic and risque, with a Bolero segment that repeats and builds and features evolution on a continuous march. I was really obsessed with the sets in that, because they were dark but colorful and they showcased this shading technique that created three-dimensionality in flat objects.

These were the inspirations for the world of The Shrine — the trees, the mountains, the rocks and everything. I don’t know if anyone has used this technique for a song that’s so long. I’ve probably listened to it 30,000 times.

The main character was originally a woman riding on top of an elk, but after a few weeks of prototypes, I realized she wasn’t necessary to the story. So the hero became the elk, and this small demon character inside of the elk. I was pushing it, trying to get it a little weirder. That was more interesting to me, and it worked better for the narrative.

I got really excited asking myself — and this is true of all the videos — what does this section of the song look like? What is it visually? The end of the song was always kind of a musical interpretation of a fight, or an argument. I wanted to see if I could get a bit abstract, allowing the music and the colors to operate as a tension.

Robin: You actually named that part of the song to begin with. I played early mixes for you, and you said the end sounds like an argument. So I named it that. Your idea for that part of the video changed the name of the song before the video even existed.

Sean: I had forgotten about that!

Robin: The guts that the dragons are pulling at the end, how’d you get those to be so taut?

Sean: The action of him playing the strings as he rides on the head to the bottom of the ocean, it looks like it could be hand-drawn animation. It’s oddly precise for paper. It was just colored yarn. The video and the production itself were so hard and long when he’s in the mountains and the desert and the forest. It was challenging to animate - the wolves chasing, the elk walking. When he goes into the fever dream, and falls into the ocean, it goes from red heat to cool ocean and, ironically, that whole scene where the two-headed monster is fighting over his carcass, was the most fun and the easiest part to animate. It took two weeks, compared to four and a half months.

Robin: Each section of the song is matched with a different lighting environment. Even when we do the song live, I see that cerulean blue at the end. You are setting the visual tone for however people further experience the song.

Third of May / Ōdaigahara

Sean: I was in Zihuatanejo, sanding an old 1940s schooner, and Robin took a bus there to find me.

Robin: My cuffs rolled up. My long hair blowing in the wind. In front of that crazy, wild ocean.

Sean: And I said, brother. I knew you’d come.

Robin: And that’s when I said, what about a Frankenthaler-inspired color-wash lyric video?

Sean: This video set the tone for the projections for the tour. When you think about motion painting, it’s often tye-dye and overhead projectors, usually a bit hippy. Helen Frankenthaler’s paintings don’t feel like that. There’s a lot of emotion in them. I hadn’t made a lyric video before, so we were kind of trying to figure out what it needed to do, and how to incorporate text.

Third of May is an insanely rich and long song with suites - distinct sections that needed to be reflected visually. It was the exercise of what would the sound look like, reflected in paint? We tried to do a lightning effect with some dusty clouds of color.

Adi Goodrich is a material and color expert, so she gets all the credit for figuring out the right viscosity of paint. We did so many tests.

We went the subtitle route with the lyrics, but then the end of it, to me, feels like a title sequence from a Samurai movie. It's like blood from a battle oozing upwards.

Fool's Errand

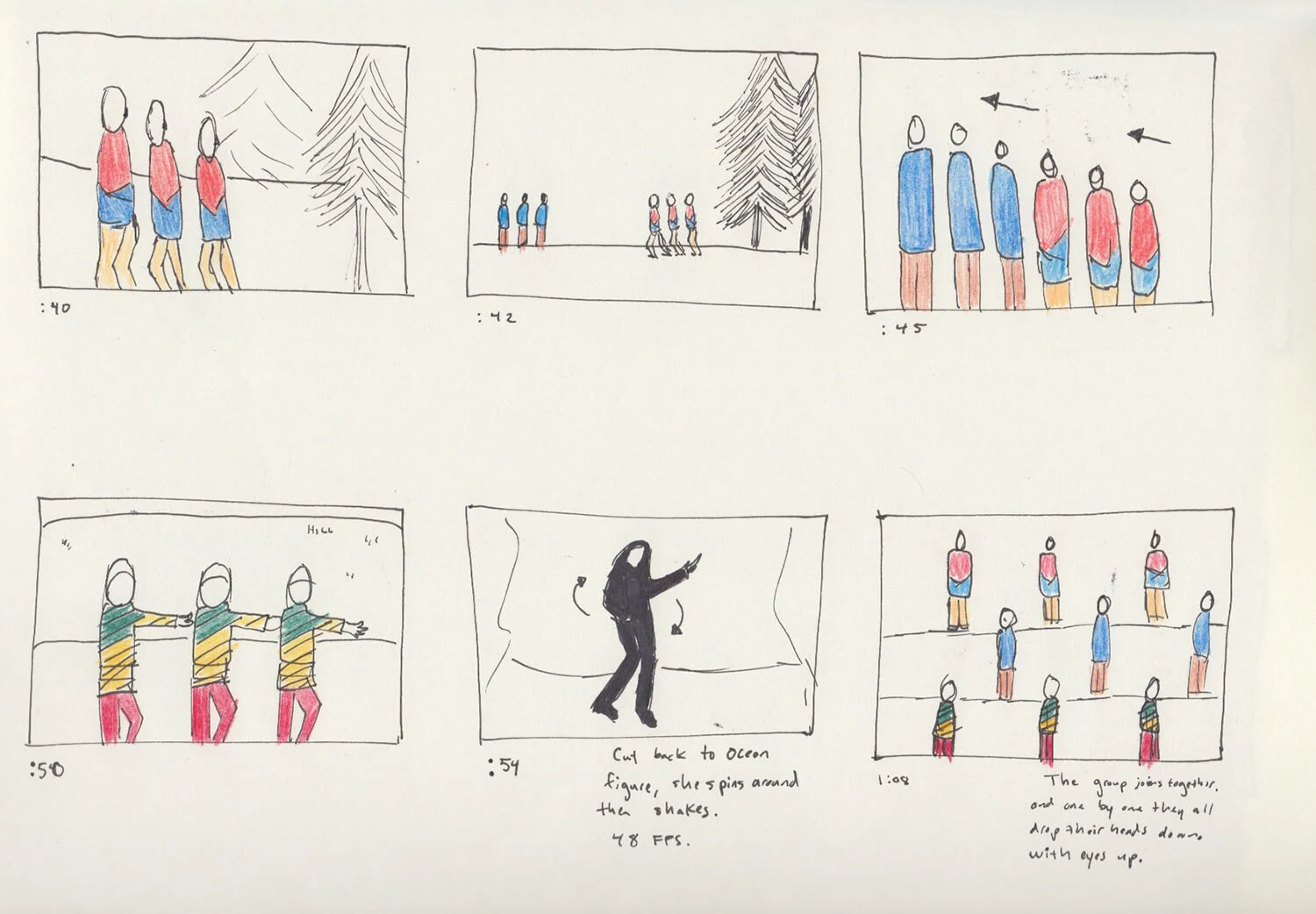

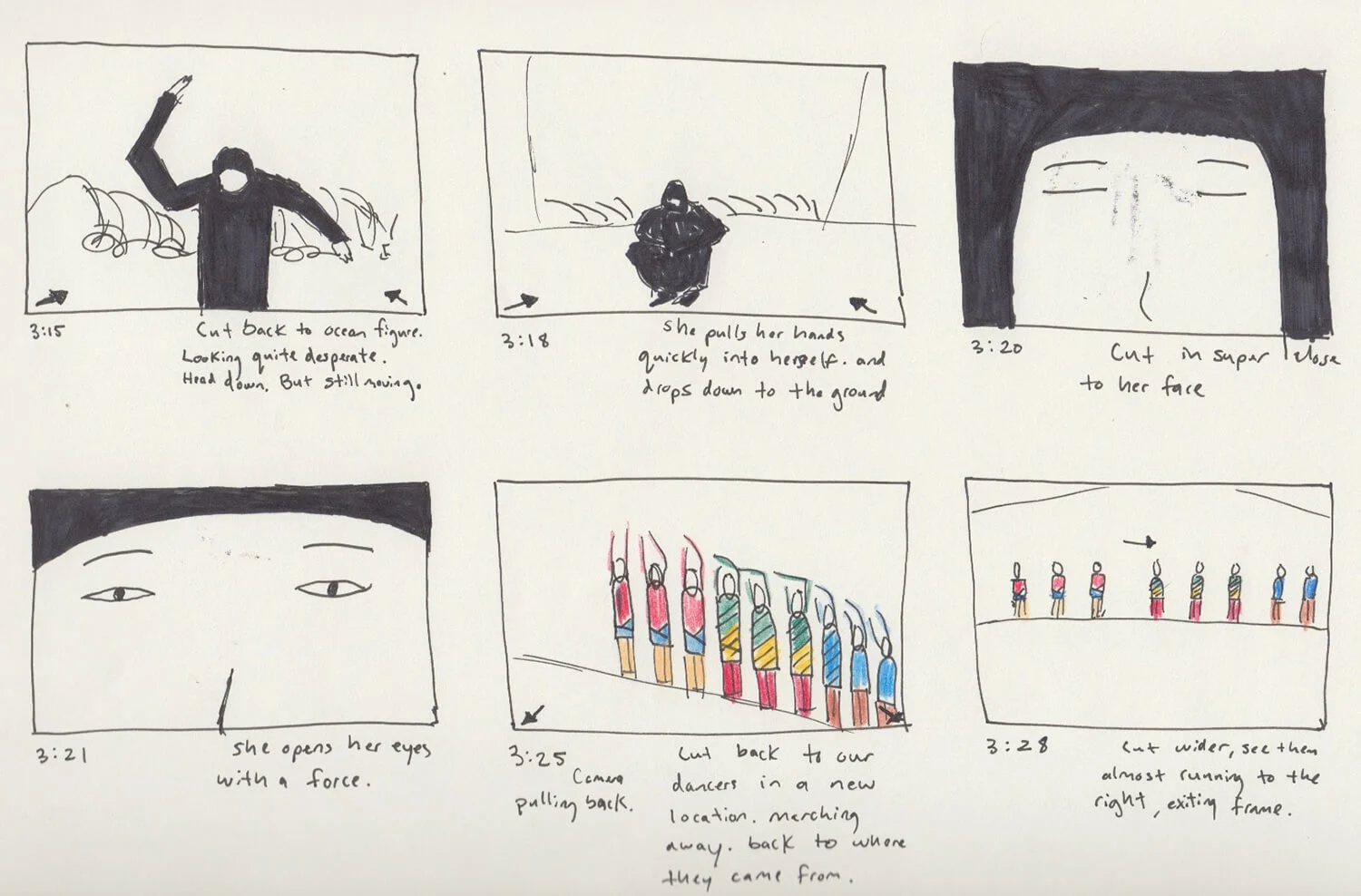

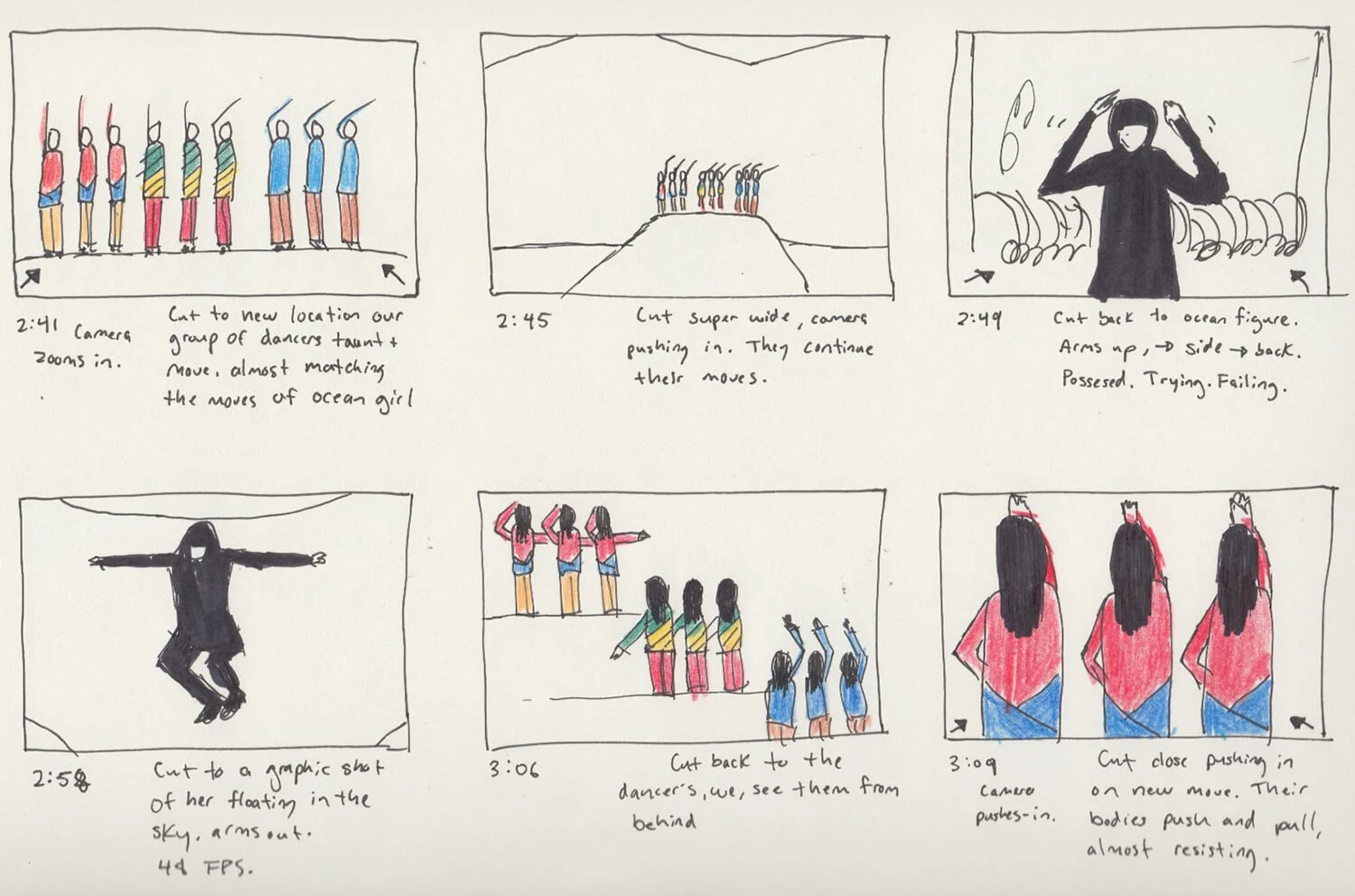

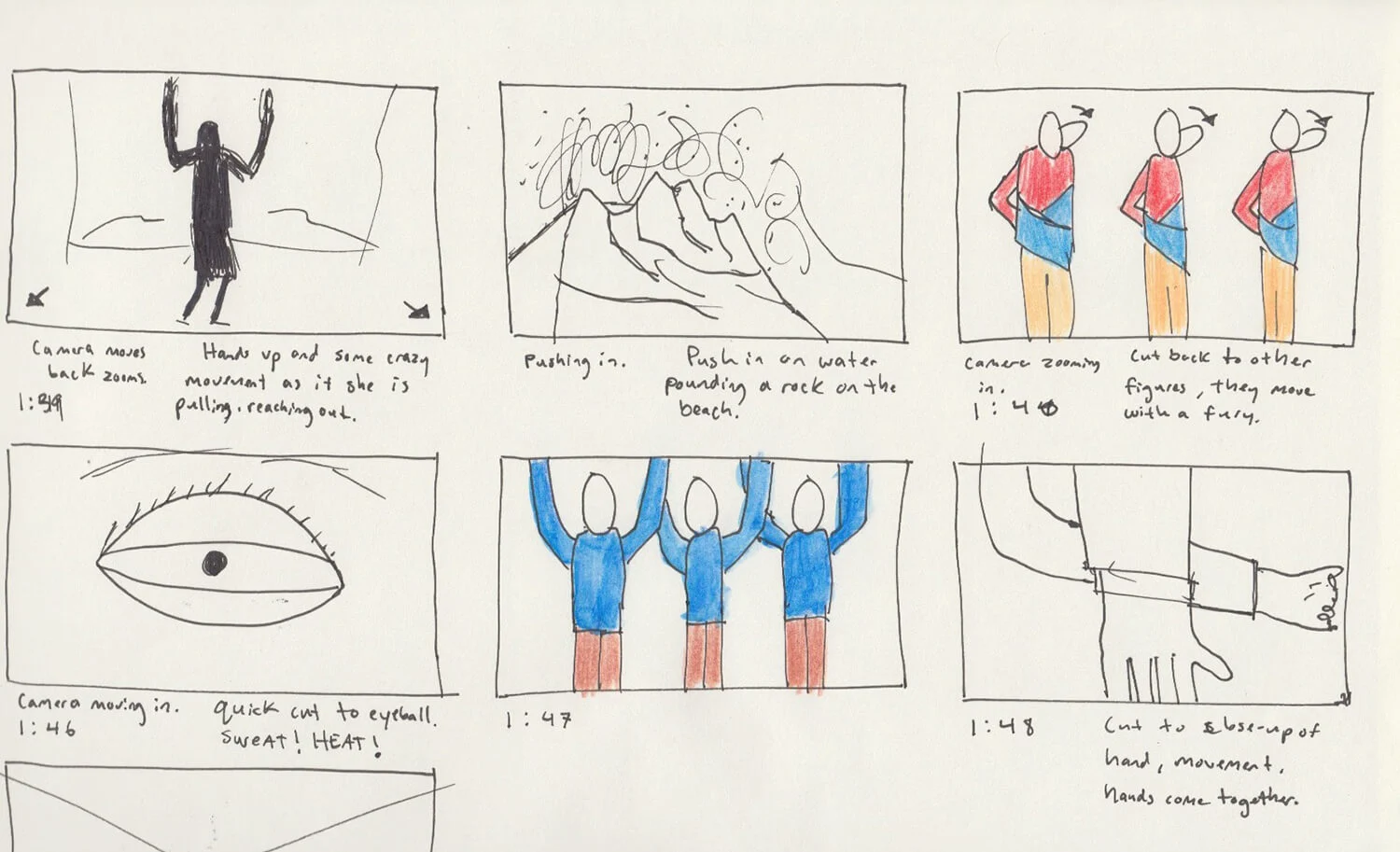

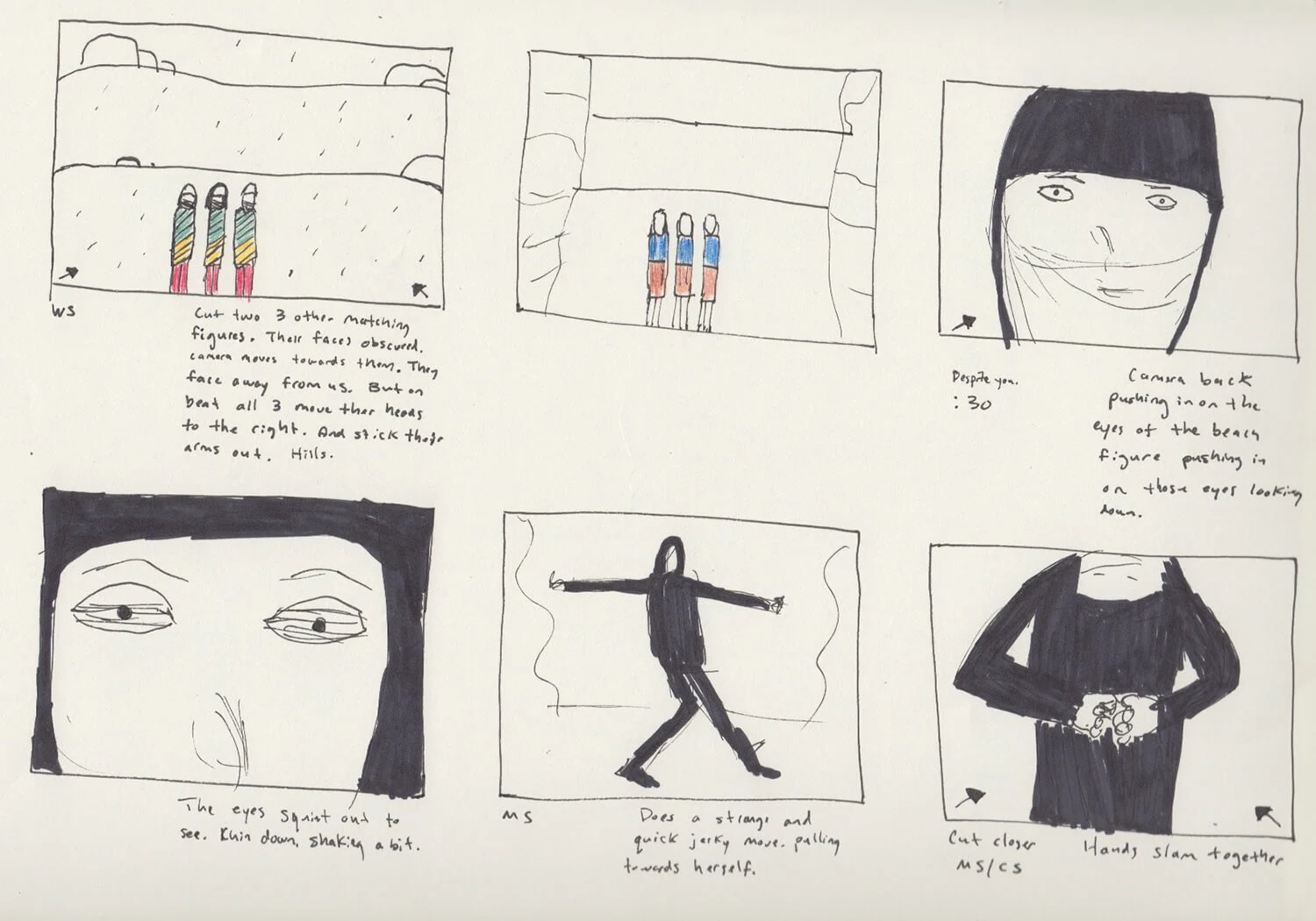

Sean: I had done a few projects with Super 16 and Super 8 , and had been dying to try regular 35mm. This was the first video where I knew I needed to draw it. I knew exactly where the moments needed to happen in the song. With film, you have to be really economical - only two takes, maybe three. So it really forces you to stay on your game.

Sean: I had a fully-formed vision before I started filming, based around a woman coming out of the ocean, going through a period of transformation.

With a lot of these videos, I have meaning that I place on the narratives and the visuals. Even with the ones that are more story-based, I have my own personal meaning in it. It’s always that balance — doing something I want to do, and something that fits the song, and something the band is into.

Sean: I got obsessed with this photograph of a person coming out of the ocean wearing ragged clothes. I was drawn to it. Kind of the same way Robin was fixated with the Frankenthaler painting. It just fit the mood. Then, I expanded that a bit to create this division of a woman transforming into a wolf, and then these rhythmic, repetitive dancers. It was kind of a metaphor for wanting something that you think is better, or more put together, in your life.

Robin: The colors are amazing. You moving to California made more sense when you have access to places like this. With this video, and with the Arroyo video, you’re able to find these really incredible locations in California. You’ve been able to give great exercises in physical landscape and adventure filmmaking when you’re lugging 100lbs of camera equipment up a mountain, getting those Kurosawa-like shots from a distance.

I Am All That I Need / Arroyo Seco / Thumbprint Scar

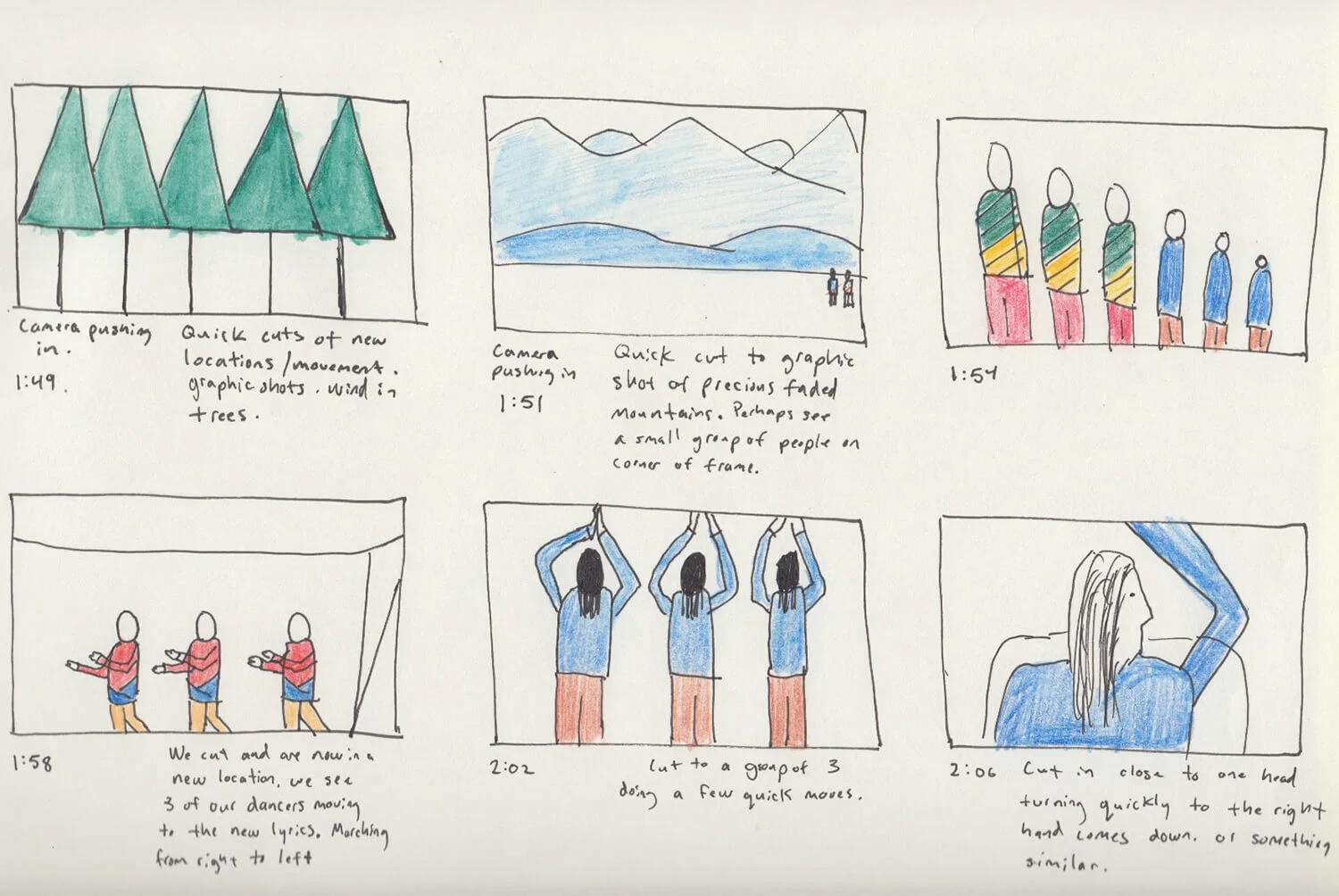

Sean: Over the last nine years, as I’ve developed into video work, I’ve found I’m really obsessed with the lighting, the timing and the story. There’s a pretty detailed animatic for the Arroyo Seco video, where I basically acted out the whole thing.

It was a four day shoot. One day at a house in Palm Springs. One day in Lone Pine, off the 395, where they used to shoot a lot of Westerns. I had seen this road, these rocks, called the Alabama Hills at a place called Diablo Lake. We shot in a studio for 2 days too, where Adi and Aaron Wiley recreated the house and made this really long hallway. It felt like a full-on production.

The box looks CG. But it’s not. It’s all in-camera.

Sean: It was the first song I heard off the record when I heard the final mixes, and it gave me a lot of energy. It still does. It stays compelling the whole time, despite the shifts and changes. Most of the long, epic songs, they’re remarkable because they don’t feel long. When they’re over, you realize how swept away you’ve gotten. This video was one of the best, and one of the hardest, most gratifying videos I’ve made.

Aja: For all of us, it felt like the album cycle would feel incomplete without a full version of this song. From the label’s point of view, it wasn’t necessarily one of the songs we were going to go to radio with. It did become a #1 hit in Latvia...

Robin: ...Latvia’s got a lot of traction. A lot of local support. Their radio format has never switched over from classical, so it was actually a pretty short song. Classical radio edit.

Aja: To see it fully realized, it feels like a true cycle. This song really embodies the whole spirit of the album for me. I think we all feel very connected to this song, I’m really glad that you were able to work on it. It’s so visually striking.

Sean: It’s a chance to revisit a song that you’ve heard and experience it anew. The song lent itself so well to visuals - the strings, the big sections. This kind of inherent, cinematic quality to it made it that much better to pair with film and make a video out of it.

Words by Emily Bernstein